Judge Judy, in a rare interview, reflects on her iconic TV show as it reaches its final season

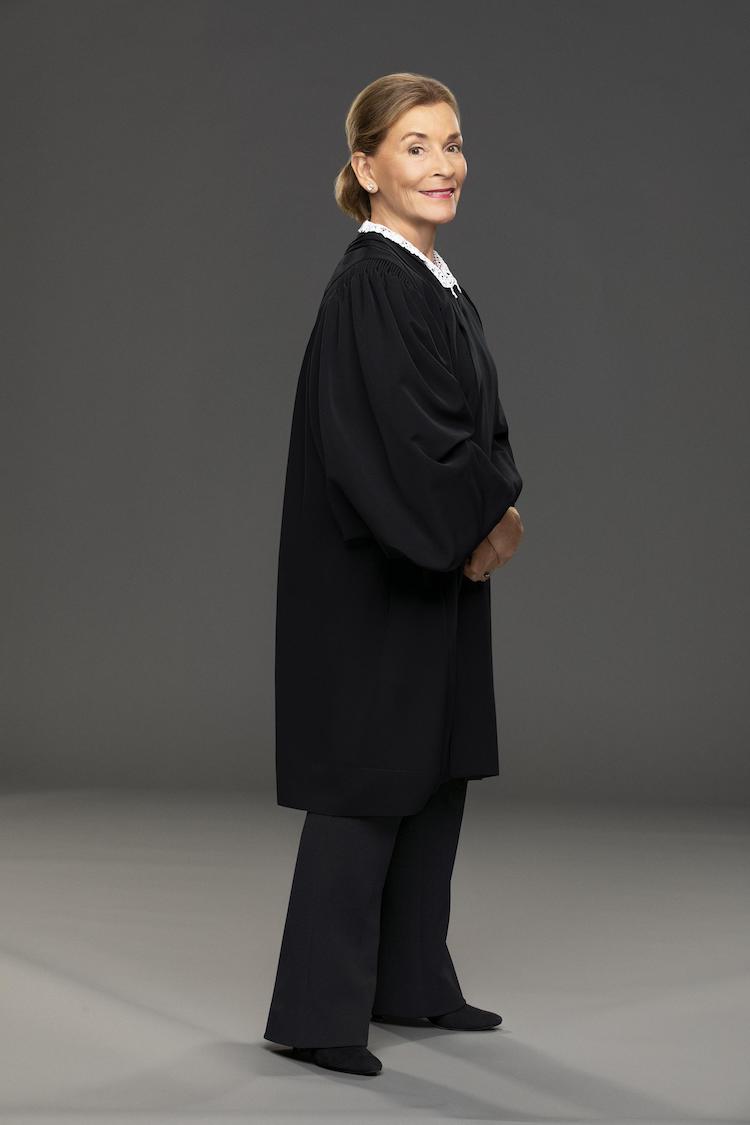

Photo courtesy of CBS Television Distribution.

In 1987, Judge Judith Sheindlin of New York County Family Court terminated a couple’s parental rights to their two young children. The mother had shown no interest in raising them. Their father had been incarcerated for several years, and his release was many more away.

In issuing her opinion that the parents had neglected their children, now freeing the youngsters for adoption, Sheindlin observed that children “do not wait in a state of limbo while their parents mature.” But the judge wasn’t finished.

“The act of becoming a parent takes only seconds, but being a parent takes dedication, hard work and sacrifice.” Sheindlin’s decision, In the Matter of Kareem B., was affirmed by New York’s highest court.

Sheindlin served for 15 years as a family court judge in Bronx County and then as supervising judge in Manhattan. Her docket included cases of child abuse, neglect, custody and juvenile crime. She stepped down in 1996 but didn’t hang up her robe. Nor did she stop speaking her mind.

Judge Sheindlin switched coasts and became known as “Judge Judy” on an afternoon television program, arbitrating small claims cases with a scalpel-sharp tongue. Her wildly successful, eponymous program is in its 25th and final season. “Judge Judy” is reality TV; however, reality prepared Sheindlin for the role.

It’s all about personal responsibility

During a nearly hourlong phone interview from her winter home in Naples, Florida, Sheindlin, 78, held court on several topics. In a warm and immensely entertaining manner, Sheindlin reflected on her program and what lies ahead.

She also had much to say about her judicial philosophy, which has not wavered in 40 years. Whether it was incarcerating a teen for committing a violent crime or resolving a dispute between roommates over an electric bill, her decisions have been based on common sense. At their core, individuals must take personal responsibility for their actions.

“I’ll give you an example,” Sheindlin offers. She takes me back to a case from 1983 that centered around a paternity test, which judges are authorized to order by statute. However, Sheindlin says, “let’s say the man does not want to appear. He does not want to be adjudicated the father, thereby avoiding the possibility of child support.” In this situation, Sheindlin explains, to her disbelief, the statute provides no remedy. Instead, judges are left to re-order the test or impose a fine on the noncompliant party.

But “there has to be a consequence,” Sheindlin insists. So, she filled the legislative void. “The very easy response is, if you fail to go, there is going to be a negative inference that the results would have been unfavorable to your position,” she says. In her opinion regarding In the Matter of Molly M., Sheindlin wrote: “The Legislature could not have intended to render the courts impotent in the face of failure to comply with an order for the [paternity] test.”

Sheindlin does not see herself as a judicial activist. “I don’t think it’s the role of judges to legislate,” she says. “But I think it’s part of their responsibility to use common sense.”

‘Don’t pee on my leg’

I’m curious where Sheindlin developed her thinking.

We take lessons from life experiences, she explains. “To me, it was my work in the family court, where I saw so many people lacking responsibly for situations they caused, blaming it on somebody else or society as a whole.”

Sheindlin also credits a lesson from her dad. “I came home from college and my father was questioning some of my grades. I started giving him all kinds of excuses why I had not performed as expected. He looked me and said, ‘Darling, don’t pee on my leg and tell me it’s raining.’”

That statement “really says it all,” Sheindlin tells me. “You are supposed to take responsibility for what you do in this world.”

Sheindlin borrowed her father’s admonition, which she says “should be etched on the courtroom walls,” for the title of her 1996 book, a scathing critique of the family court system.

Unlike many of her fellow family court judges, Sheindlin opened her courtroom to the press. According to Sheindlin, prior to Ed Koch becoming mayor of New York City in 1978, the family court was a “dumping ground for incompetence.” She points to a judge who could not read and other judges who came back from lunch drunk.

“I said to myself, if the press ever saw this gaggle of nincompoops … the public would be outraged. So the press was welcome in my courtroom.” They could not report the names of the juveniles, Sheindlin assures me. Her other rules: sit in the back, be quiet, no gum chewing and no reading the paper.

Photo courtesy of CBS Television Distribution.

Photo courtesy of CBS Television Distribution.

A woman’s road to the bench

The Brooklyn-born Sheindlin knew from an early age that she wanted to pursue a career as a lawyer. “I was lousy in math and chemistry,” she says laughing.

“[For] most of the young woman of my generation, their plan was to marry and have a family,” Sheindlin says. “I always felt that it would be great to be a woman who had a profession that separated you from the rest of the pack.”

The would-be judge started at American University in a joint undergraduate and law program where she was only woman in her law school class. She transferred to New York Law School after getting married. While Sheindlin says that American was “welcoming” to a rare female presence, she cannot say the same for New York Law School. She recalled a question posed to her from a professor: “Why are you taking up the seat of a man who is going to have to support a family?”

Sheindlin earned her law degree in 1965. After a couple of unfulfilling years as a corporate lawyer, and then raising a family, she had her first stint in family court, serving as a prosecutor for 10 years. In 1982, she was appointed to the bench by Koch.

Again, being a rare female presence brought out the sexism existing at the time. Sheindlin shares the story of entering a lunchroom used by criminal court judges. A judge approached her and stated: “Little girl. This a lunchroom for judges only.” While Sheindlin says that she could have introduced herself, she instead went around the room and collected paper plates and placed them in the trash. The “old codger,” Sheindlin recounts, was infuriated for being made to look like a fool in front of his colleagues.

Becoming a celebrity judge

The judge’s no-nonsense style drew the attention of the Los Angeles Times, which profiled her in 1993. Next came a segment on 60 Minutes. Sheindlin allowed the iconic news magazine to film in her courtroom, bearing witness to “a 5’2” package of attitude with a capital A,” as correspondent Morley Safer described her.

Following this exposure, Sheindlin was offered a courtroom television show. Judge Judy premiered in national syndication in 1996 and became a ratings juggernaut. Last year, the show averaged 9 million daily viewers and one in three Americans watched it.

But after 6,500 episodes and 12,500 cases, give or take, the three-time Emmy-winning program is coming to an end. The final season is now on the air, and the last episodes are being taped in Los Angeles. Sheindlin’s tough talk will live on in reruns. Next up: a show on Amazon’s IMDb streaming service.

Sheindlin is mum on the details. She’ll be a judge is all she’ll reveal. “I like to work,” Sheindlin tells me. “This will give me the opportunity … to do what I do best … I’m not going to be selling jewelry on QVC.”

“Judge Judy” is licensed in over 100 international territories. “I get mail from all over, including Zimbabwe,” Sheindlin says with a chuckle.

How do foreign audiences react to the program? Just as here. “Human emotion is the same,” Sheindlin says, “irrespective of what language you speak or where you are in the world. People like to see the right thing happen and the bad guy get a little bit of a whoopin’ once in a while.”

A 2019 New York Times Magazine feature listed Sheindlin’s 2018 salary as $47 million. Forbes recently put her net worth at $445 million.

I ask the woman who has been satirized by Saturday Night Live about her midlife adjustment from one of relative anonymity to mega-celebrity. “People [now] worried about whether or not I was comfortable. Whether I needed iced tea,” Sheindlin jokes.

Some young people, lacking life experiences, have problems with the adjustment, Sheindlin says. “[But] I was a fully cooked human being at 52. I was a wife and a mother and a grandmother a couple of times. I knew how to take care of my own home. Keep it tidy. I knew how to cook. I knew how to negotiate moving my car from alternate sides of the street.”

Surely Sheindlin has a few cases from her program that she’ll never forget. “I don’t have any from the last 25 years,” she says, to my surprise. It is the cases from her days as a family court judge that Sheindlin says she will remember.

It is those that “involved grave injustice that the system had worked on people. And because of lazy judging over the years, families and people’s lives were destroyed … Those are the cases that stay with me.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.