Len Elmore's journey from the basketball court to the courtroom and back again

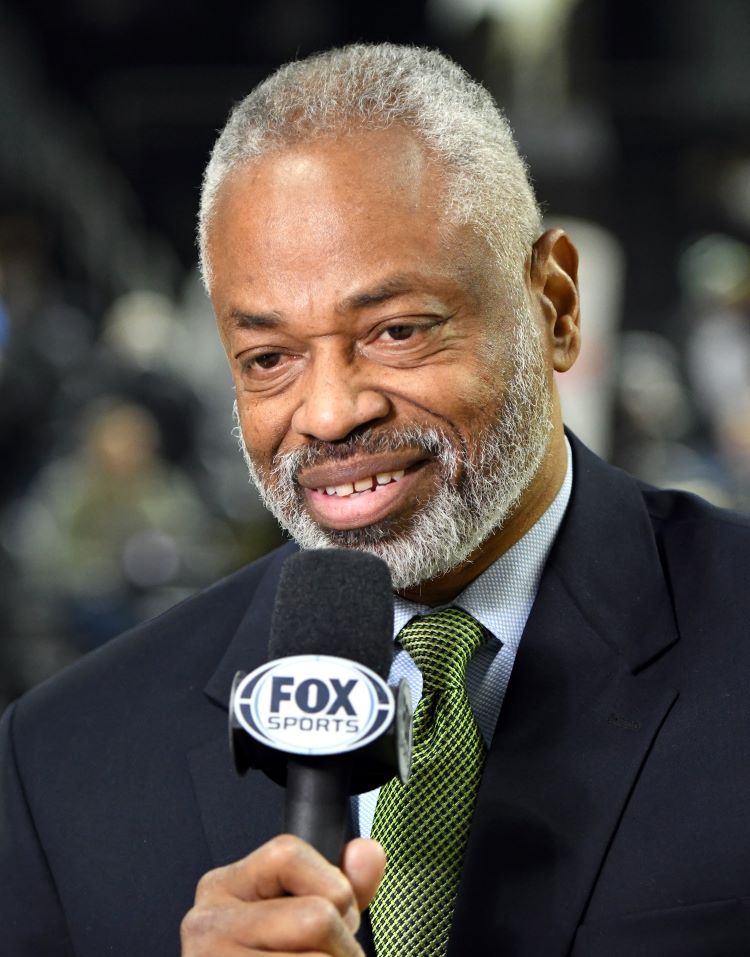

Len Elmore on air before a college basketball game between the Butler Bulldogs and the Providence Friars at the Dunkin’ Donuts Center in January 2018 in Providence, Rhode Island. Photo by Mitchell Layton/Getty Images.

It isn’t easy getting a seat in a classroom at Harvard Law School. Len Elmore did. But then the 6-foot-9-inch student was choosey about the one he took. “I tried to sit on the end of the row,” he says. “There was more legroom.”

Elmore’s road to Cambridge was a pivot, following his retirement from the New York Knicks after a 10-year career as a professional basketball player.

The former NBA center graduated from the elite law school in 1987 and went on to have a diverse career as a lawyer. Throughout it, he also traveled. Elmore served as a college basketball announcer, including over 20 years behind the microphone, for CBS Sports, for the NCAA Men’s Basketball Tournament.

On Sunday, the NCAA will reveal the 68 teams selected to play in this year’s tournament. In a wide-ranging phone interview, just ahead of college basketball’s annual madness, the three-plus decades broadcaster shared his journey from the basketball court to moot court to courtrooms. Along the way, Elmore courted college athletes as a sports agent. He is now holding court as a senior lecturer at Columbia University in New York City.

While he was at it, Elmore broke down—in a way that only a lawyer could—what is widely considered the greatest college basketball game of all time. Elmore was at announcer’s table for it.

Elmore, 69, grew up in a Brooklyn housing project. After fourth grade, his parents, both employed by the New York City sanitation department, moved the family to a small house in Queens.

He had thought about being a lawyer since childhood. “Against the backdrop of the civil rights movement as well as … the war in Vietnam,” he says, “I thought that the law could be a vehicle for change. I wanted to be in the parade and not be a bystander. So, I kept that idea with me.” “Obviously,” he adds, “basketball got in the way.”

Following a career at the University of Maryland—where he is still the school’s leading rebounder—the All-American and English major was selected by the Washington Bullets as the 13th pick in the first round of the 1974 NBA draft. Because of a much more lucrative offer, he instead chose to sign with the then-ABA’s Indiana Pacers, which joined the NBA two years later.

‘This is where I belong’

After nearly a decade, Elmore says he realized, “I’m not getting any younger, and it’s time to prepare for the next stage. Obviously, we weren’t getting paid like these guys today.”

Elmore rattles off a list of quality law schools where he applied. But his then-girlfriend, now wife, “challenged” him. “‘If you’re going to do it,’ she said, ‘why not try for the best?’”

“Almost as a lark,” Elmore tells me, he filled out the Harvard application. “I did it by hand, and I even actually crossed out something,” he recalls with a laugh. “Because I never really thought that I’d get in.”

But he did. “I’m not going to say that my LSATs were the highest. But I think I was representative. And the law school looks for a diverse community—people who bring different things.”

Soon after, Elmore found himself in Boston to play against the Celtics. He headed to the school for a look-see. “I walked around the Square. I walked on campus. Went through Langdell Library. And finally, it just hit me: This is where I belong.”

As an older student, Elmore says he brought with him the benefit of real-world thinking. “[I’d seen] real people, understood real lives.”

Being a former NBA player, he says, also worked against him. “There were skeptics out there, without question,” he tells me. “Maybe even among some of my professors and certainly among some of my classmates. But I think I put them to rest in the first couple of weeks where I could hold my own with my professors.”

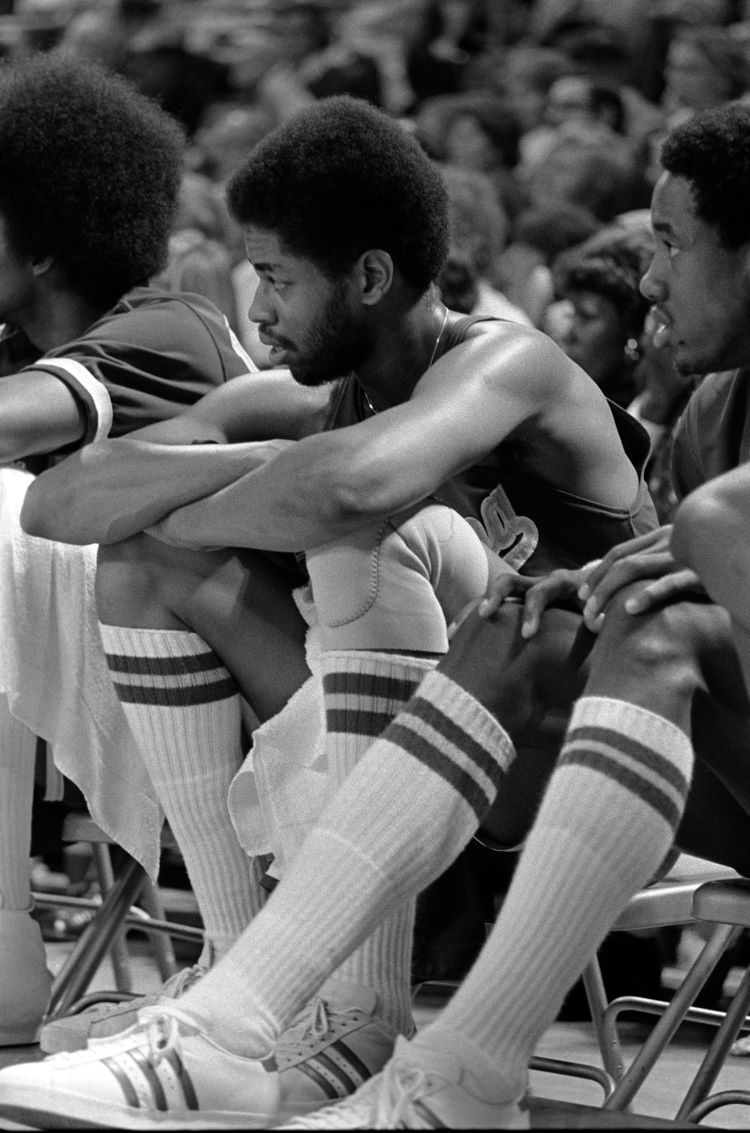

Indiana Pacers center Len Elmore, #41, sits on the players bench during an ABA basketball game at the McNichols Arena in March 1976 in Denver. Photo by Mark Junge/Getty Images.

Indiana Pacers center Len Elmore, #41, sits on the players bench during an ABA basketball game at the McNichols Arena in March 1976 in Denver. Photo by Mark Junge/Getty Images.

A diversified career

Elmore’s introduction to the profession was a four-year stint in the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office where he focused on trying police misconduct cases. On weekends, he headed out of town to broadcast Atlantic Coast Conference basketball games.

He loved being a prosecutor, he tells me, but not the salary. Living on the Upper West Side and looking to start a family, it was time for Elmore to move on.

His career in the private sector—with broadcasting in the mix at various times, including for Fox and ESPN—was varied. It included serving as a sports agent, positions with Patton Boggs and LeBoeuf, Lamb, Greene & MacRae, corporate consulting and CEO of an education technology company to help students with standardized tests.

Elmore had success as an agent, but he didn’t have what it took to maintain it. The sports management company he started, and ran for five years, represented seven first-round NBA draft picks and a couple of high NFL draft picks.

But as pro basketball players began getting paid more, Elmore says the competition was “willing to do anything” to sign college athletes. The unscrupulousness was not for him. “I made a decision, in order to maintain our success, in order to grow, I’d have to do the same things they were.”

Elmore describes going into homes to make pitches to prospective clients.

“‘Well Mr. Elmore, that’s great,’” would be the response that followed. But then they’d ask, “’How much money can you give us now, because so and so just offered us x.’” Elmore tells me that all he could offer was his best wishes “because I don’t do that kind of stuff.”

For the past few years, Elmore has been teaching in the graduate sports management program at Columbia, including “Athlete Activism and Social Justice,” a course that grew out of the situation involving the NFL’s Colin Kaepernick and his decision to kneel during the National Anthem.

The class traces the history and methods of many Black athletes, going back to the 1800s, using their platforms to influence social justice. This is examined, Elmore says, “against a social, political and economic backdrop that exploited and victimized underrepresented folks.”

Elmore foresees his sports management students as “the C-suite dwellers of the future.” He says athlete activism “is not going anywhere,” and the course teaches the “impact that [the students] can have, not only with the athletes, and certainly on the athletes. You have to know your history before you can even construct the future.”

Elmore also works to bring awareness to social justice in collegiate sports as part of his role as co-chair of the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. The organization—not affiliated with the NCAA—describes as its mission “to develop, promote and lead transformational change that prioritizes the education, health, safety and success of college athletes.”

Pushing for greater diversity and inclusion

Elmore’s efforts have included encouraging schools to increase the number of Black coaches and athletic directors and administrators. Last month’s racial discrimination lawsuit, filed in federal court in Manhattan, by fired Miami Dolphins head coach Brian Flores, brought attention to the National Football League having just two Black head coaches among its 32 teams, while 70% of its players are Black. It turns out that the numbers are just as lopsided on the college football sidelines.

A May 2021 Knight Commission report, prepared by a task force that Elmore chaired, revealed that, in 2020, just 10% percent of the 130 NCAA Division I head football coaches were Black, while 50% of the players were.

Elmore points to several ways in which improvements can be made, including “bringing broader attention” to the problem. There needs to be “more scrutiny and greater pressure on people to act.”

He also says, “If there are rules and policies that mandate a broader search and greater inclusion, people will act accordingly based on their integrity and ethics.”

Elmore calls out the College Football Playoff Board of Managers for its unwillingness to set aside even 1% of its $500 million annual distribution to member schools, for a “program that will create, explore, expand and expedite diversity, equity and inclusion among college football coaches.”

Of Elmore’s varied career, he says, “Anytime there was an interesting opportunity, rarely did I turn it down. That’s why I’ve done so many things.”

Elmore called the 1992 NCAA Tournament East Regional final between Duke University and the University of Kentucky. The game culminated with Duke’s Christian Laettner catching a near full court-length inbound pass and hitting a turn-around jumper—with less than one second remaining on the overtime clock—to give the Blue Devils the win. The moment is now known in sports circles simply as “the shot.”

Elmore recounts the game—and then returns to his days as a prosecutor to charge the Wildcats for letting it happen: “Kentucky’s willful failure to put a man on inbound passer, Grant Hill, and their negligence in not going after the 75-foot pass while it was in the air, and before Laettner caught it, amounted to a reckless disregard for the win.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.