Even Death Can Be Political: An interview with forensic pathologist Michael Baden

Michael Biden is the author of American Autopsy: One Medical Examiner’s Decades-Long Fight for Racial Justice in a Broken Legal System.

It was May 29, 2020. Michael Baden, like most Americans, was holed up at home. For days, he had seen images on television of a lifeless George Floyd, his neck pinned to the ground by the knee of a Minneapolis police officer.

That morning, the Hennepin County attorney announced results of a preliminary autopsy of Floyd: There were no physical findings that his death was caused by traumatic asphyxia or strangulation. Police restraint was not to blame.

Baden tells me what he recalled thinking: “It sounds like the cover-up has already started.”

At noon, his phone rang. A voice on the other end asked whether he could come to Minneapolis. “Today, if possible.” Two days later, Baden had a much different view of Floyd’s body. The renown forensic pathologist was standing over it on an autopsy table.

The request to provide a second opinion of Floyd’s death came from Ben Crump, the longtime civil rights attorney. Crump, representing the Floyd family, was aware that medical examiners, despite their supposed role as independent scientists, sometimes looked for ways to shift blame from law enforcement onto victims.

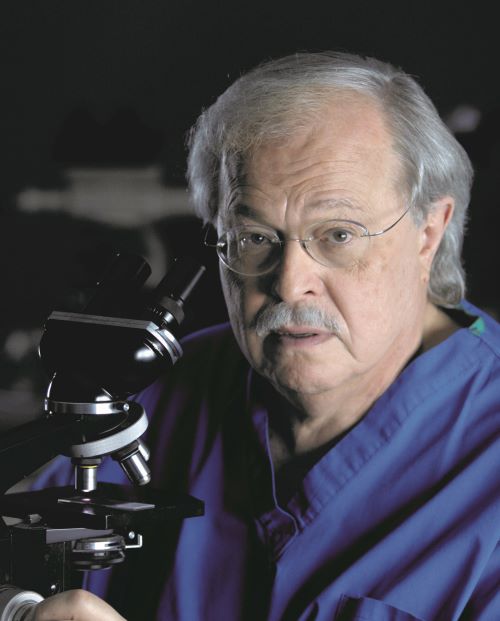

Baden also knew this well, having performed over 20,000 autopsies and reviewing tens of thousands more. So despite the COVID-19 travel risks for the then-85-year-old, he left his home in the Catskill Mountains and headed to the Twin Cities. Baden tells me he knew it was an important case, and he was “eager to do it. This was something that I had an interest in.”

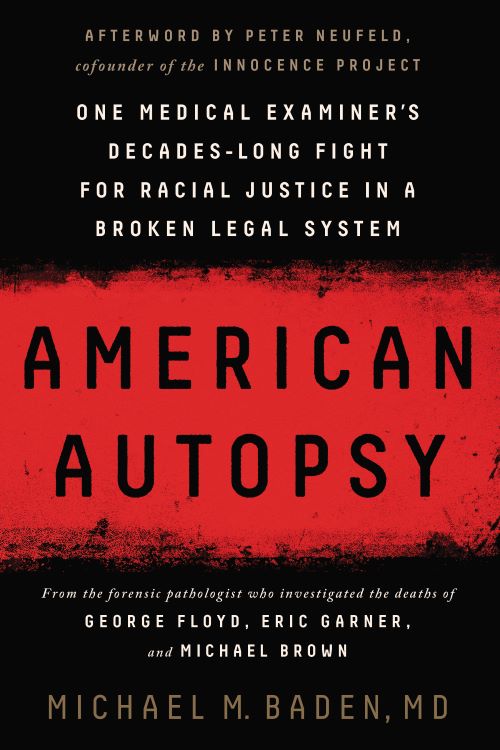

This interest is the subject of his recently published book, American Autopsy: One Medical Examiner’s Decades-Long Fight for Racial Justice in a Broken Legal System. In a recent interview in Midtown Manhattan, Baden discussed the book in which he recounts fascinating—and oftentimes shocking—cases of medical examiners believing themselves to be “part of the prosecution team” by looking for ways to “help police and prosecutors defeat the ‘bad guys.’”

Among the stories Baden shares are his involvement in high-profile cases such as the police encounter deaths of Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York, and Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. The causes of death for these Black men were controversial.

Baden also recounts his work in historical cases, including leading a group of forensic pathologists in the mid-1970s that was part of the United States House of Representatives Select Committee of Assassinations’ investigation into the deaths of President John F. Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In 1991, he performed an autopsy on the exhumed body of Medgar Evers, nearly 30 years after the civil rights’ leader’s death. That work played a part in the state of Mississippi’s successful prosecution of Evers’ assassin.

In addition to frequent appearances on cable news, Baden spent many years as host of HBO’s docuseries Autopsy.

Path to pathology

Baden didn’t set out to be a forensic pathologist. The Bronx, New York, native and New York University School of Medicine graduate was an intern at Bellevue Hospital preparing for a career in internal medicine. But three nights a week, he moonlighted at the New York City Medical Examiner’s Office.

This led to a fascination with anatomy—as well as a realization, he tells me, of a difference between the two disciplines. As an internist, Baden says, “I could only treat patients one at a time.” But a forensic pathologist, he explains, can learn “things that could help lots of people.”

Baden chose forensic pathology, despite the field “being looked down on by the medical establishment.” Back then, he says, it was seen as a “dumping ground for alcoholic and incompetent doctors who couldn’t make it in the lifesaving business.”

The office’s once-part-time assistant would rise to become New York City’s chief medical examiner. He later spent 25 years with the New York State Police, rising to chief forensic pathologist.

Body politics

The first time Baden considered that “maybe medical examiners aren’t as independent as I thought” came in 1967. Eric Johnson, a Black and mentally ill inmate at New York City’s Rikers Island jail, died in his cell.

The official account was that corrections officers had come to give him medicine for seizures, but he refused. Johnson made a “cutthroat gesture.” The officers, taking this as a sign that he would resist, put on masks and fired a teargas cannister into his cell. They took Johnson out. He was dead.

Milton Helpern, the city’s chief medical examiner, performed an autopsy. It was unusual for the top doctor to do so in a seemingly routine case. Helpern concluded that he died of natural causes, terming it “psychosis with exhaustion.” In other words, Johnson had gotten so excited during the encounter that he collapsed and died.

Baden, a member of Helpern’s staff, examined Johnson’s body and saw a different story. The presence of petechial hemorrhages, tiny red marks indicating ruptured capillaries, suggested that Johnson had died from neck compression.

Baden learned that Mayor John Lindsay had received an anonymous tip that Johnson had been beaten by white guards. The mayor contacted Helpern, expressing concern that Rikers inmates would riot if they learned what happened to Johnson.

“Helpern’s ruling had more to do with politics than science,” Baden says. But not wanting to upset his relationship with his mentor, he stayed quiet.

“Johnson,” Baden says, “became a statistic.” He was “just another Black man who died in police custody of natural causes.”

A wiser Baden was now onto how some medical examiners handled fatal police encounters, especially ones involving restraints, chokeholds and back pressure. He realized “just how far some medical examiners would go to cover up possible police misconduct.”

Baden says he learned a valuable lesson. “Forensic pathologists,” he says, “are scientists in a political position. We have to fight political pressure, not just bow to it. We have to tell the truth, no matter what the personal cost.”

And costly it was.

Job insecurity

In 1978, following six years as New York City’s deputy chief medical examiner, Baden was appointed to the top spot by Mayor Edward Koch. One year later, the mayor demoted Baden. Koch’s about-face was tied to letters he’d received taking issue with Baden’s performance.

In one, Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau complained that Baden’s office had found no scientific or physical evidence that a murder victim had been raped, despite the DA charging the offense.

As Baden saw it, the demotion was a response to city officials’ dissatisfaction with the independence of his office. He filed suit in New York federal court. Despite winning reinstatement, the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, in Baden v. Koch (1980), reversed.

The appeals court concluded that the chief medical examiner is appointed under the city’s charter, which allows for removal without cause. The court rejected his argument that the CME is a civil service position, requiring cause as a basis for termination.

The decision was purely procedural, and the court noted that it “in no way passes upon the truth or falsity of the complaints against Dr. Baden or upon the wisdom of his removal from office.”

Most medical examiners, Baden explains, do not enjoy civil service protection. They serve at the pleasure of whichever governmental official or board appointed them. Such an arrangement, Baden says, sets up a potential clash between their scientific independence and political pressure.

In a system without civil service protection, “medical examiners are like baseball team managers,” Baden says. “They can be there for a while. Then they have to leave, or they’re fired and they get a job elsewhere.”

Anatomy of murder

In the case of Floyd, Baden concluded his death was a “homicide caused by asphyxia due to neck and back compression that led to a lack of blood flow to the brain.” In contrast to the official account, Baden found no significant heart muscle damage and the fentanyl in Floyd’s blood did not cause his death.

Baden terms Floyd’s cause of death “positional asphyxia.” It occurs, he explains to me during a detailed anatomy lesson, when compression against the chest prevents expansion of the lungs. Baden notes that it can also take place when one is on their stomach and there is pressure placed on the back. “This is the time that police are handcuffing a disobeying person,” he says.

Hours after Baden announced his conclusion, the official cause of Floyd’s death was changed to “cardiopulmonary arrest complicating law enforcement subdual, restraint and neck compression.”

Baden explains that in cases of positional asphyxia, there may be no evidence found during autopsy of internal or external injury. “A lot of medical examiners,” he says, “feel that they can’t make a diagnosis of prone back pressure because nothing shows up at autopsy. And they will then blame it on the drug that was taken, if there was a drug, or we all have some degree of coronary artery disease.”

“This,” Baden says firmly, means that when it comes to police encounter cases, “autopsy must begin” at the scene of the incident.

Twenty thousand-plus autopsies. I just can’t get my head around that number. A lifetime of death on a daily basis. Baden has heard this before. “Doing autopsies is not a depressing function,” he says. What’s upsetting is when “I was treating patients at Bellevue Hospital who were dying of metastatic cancer or severe heart disease and I couldn’t help them,” he explains.

“The people I deal with have no pain.”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.