Good cop, bad cop: What happens when police get too cozy with informants?

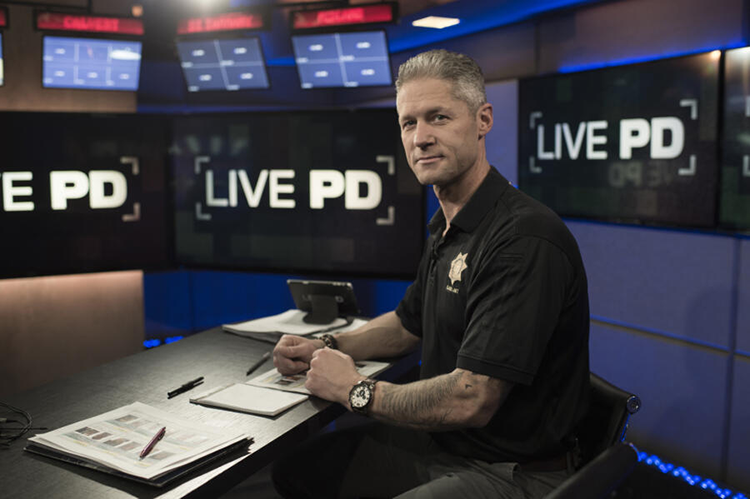

Sgt. Sean “Sticks” Larkin on the set of Live PD. Photo from A&E.

Over a year ago, I wrote a column for my “law and pop culture” series regarding the A&E show Live PD. In that column, I spoke about the problems these types of series can cause for defendants and law enforcement.

In Oklahoma, where I practice, Live PD has tainted more than one law enforcement agency. After what can only be described as a less than positive experience overall—as I noted in the prior column—the Tulsa Police Department “declined to renew its contract with the show after the Tulsa police chief argued the agreement ‘was not in the best interest of the department.’”

Sgt. Sean “Sticks” Larkin was one of the prominent officers featured in the Tulsa PD Live PD iteration. In May 2021, Larkin announced his retirement from that agency, perhaps to focus on a television career that has included gigs as an analyst for Live PD and the spinoff PD Cam.

However, Larkin’s decision to retire may not have simply been motivated by his newfound television opportunities.

‘Coptales and Cocktails’

For one, Larkin has a relatively new podcast he is promoting. Coptales and Cocktails features Larkin and his co-host, an ICU nurse. The podcast’s theme revolves around different aspects of law enforcement, discussed while everyone enjoys an alcoholic beverage (hence the program’s title and sponsor, a whiskey reviewing blog). After reviewing a few episodes, I felt like other attorneys I had heard from: not a fan. Granted, much like most cops probably don’t enjoy hearing criminal defense attorney bragging rights, the same holds true from the other side of the fence.

However, a more significant explanation for my response involves the specific subject matter of one of the episodes I listened to. In that installment, Larkin interviewed one of his former confidential informants, “Connor.” Larkin no longer works with “Connor” (whose actual name was withheld), but the two recounted many of their interactions together while Larkin drank and Connor smoked weed.

Now, I don’t mind him ingesting marijuana in the slightest. Oklahoma allows for medical marijuana. I took a bit of offense, though, to two things. First, it was off-putting when Larkin cast Connor as just a guy with a “good heart” looking out for his neighborhood and city. That description was in light of admitting the two were introduced because Connor was a drug dealer flipped to Larkin by one of his associates. Additionally, Connor wasn’t just working as a CI because he is a “good guy”—he was getting paid as well. (Yes, informants can get paid by law enforcement.)

Secondly, one passage in which the two reminisced about Connor texting Larkin updates during a criminal hearing made my spider-sense tingle. Courts employ the rule of sequestration during hearings and trials for a reason. Witnesses are not supposed to be aware of other witnesses’ testimony. The fact that these two were so chummy that Larkin used this avenue of communication, or at least allowed it, made me wonder what else may have gone on behind the scene.

Protecting ‘bad cops’?

Cover image from Simon & Schuster.

Cover image from Simon & Schuster.The other potential reason behind Larkin’s retirement involves his new book, Breaking Blue: Real Life Stories of Cops Falsely Accused—and perhaps even more so—the motivations behind that book.

According to the Tulsa World, Larkin was one of the officers who became compromised and barred from testifying in federal court due to his involvement as an unindicted co-conspirator in a police corruption probe that became public in November 2009. The allegations involved officers stealing evidence while investigating drug offenses. Larkin’s law enforcement colleague, former Officer Jeff Henderson, was acquitted of multiple counts but ultimately found guilty of perjury and civil rights violations, leading to his incarceration.

Interestingly, Henderson just so happens to be one of Larkin’s most recent podcast guests.

Larkin’s involvement as an unindicted co-conspirator means he was never charged, so to be fair, he never had his “day in court” or the ability to try and clear his name by maintaining—and establishing—his lack of guilt through trial. Still, the resulting stain of the allegations, along with “incidents as far back as 2007 in which Larkin was accused of improper conduct at work,” have been difficult for Larkin to wash away.

According to Larkin, “When you are Giglio’d, there is no way to defend yourself … it’s career-ending for a lot of people.”

Giglio v. United States

Larkin was referring to Giglio v. United States, the seeds of which began with Brady v. Maryland. Pursuant to Brady, the prosecution violates a defendant’s right to due process when it withholds evidence that is material to either guilt or innocence.

In Giglio, the Supreme Court held that the prosecution’s obligation to disclose evidence that could exculpate a defendant or reduce the penalty extended to impeachment evidence (evidence that a witness has made statements or committed acts that could be offered to draw question as to the believability of the witnesses’ testimony). The obligation holds firm regardless of whether there is good or bad faith on the part of the prosecution, and suppression could be the proper remedy if such evidence is withheld.

To put it more succinctly, it did not matter whether the failure to disclose was intentional or negligent—disclosing Giglio information remains the responsibility of the prosecutor as a representative of the government. After Giglio, and in conjunction with Brady, when a prosecutor calls a law enforcement officer as a witness, that prosecutor has an affirmative obligation to disclose impeachment evidence, even if they are not personally aware of the Giglio material.

As a result of the court extending the Giglio decision to law enforcement, when prosecutors don’t turn over potential impeachment evidence regarding their law enforcement witnesses, the proper remedy could be suppression of the witness’s testimony (if discovered prior to trial). If the issue is discovered after conviction and during appeal, the remedy can be a new trial for the accused.

Recent reform measures

Like so many other professions, law enforcement officers—and by extension the prosecutors who work hand-in-hand with them and knowingly or recklessly endorse their testimony—harm themselves when they fail to “out” the bad apples in the bunch. A new development, however, could hopefully lay the groundwork for much-needed reform.

According to CNN, “In response to the police killing of George Floyd, 15 unions that represent law enforcement officers across the U.S. have endorsed a blueprint for policing that includes an unprecedented shift in the way unions protect bad police officers.” The plan is simple: Step in when you see another union member doing something wrong.

This new framework would “empower local union members to speak up and take action if fellow members are violating their professional oath or abusing their power and ultimately helps the union weed out wrong-doers from union membership.” This, in turn, would also give the unions more discretion in looking at the merits of an officer’s actions when deciding whether or not to defend said officer’s conduct.

The move could rightfully break up decades of union solidarity. Very notably, the Fraternal Order of Police, which represents 356,000 members across the country, was not involved in developing the plan.

It goes without saying there is a massive difference between a cop who lies and a cop who kills. Consequently, officials have acknowledged that this program likely will not alter, to any discernible degree, the tragic number of police shootings in our country. Still, it “could lead to a change in the smaller, less consequential” actions of police officers.

If it does nothing more than stop some cops from lying, cheating and stealing, that’s at least one foot in the right direction on a path that will take years, if not decades, to traverse.

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney of the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. His practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes and white-collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.