Chemerinsky: 2022 contained a week that dramatically changed constitutional law

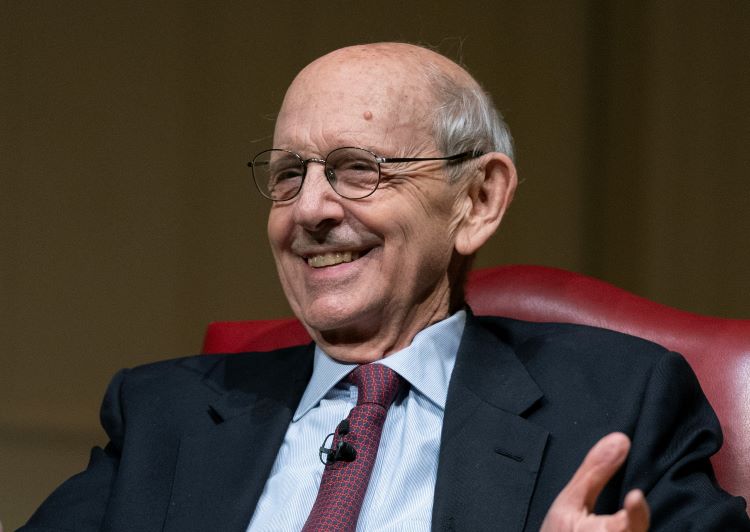

Erwin Chemerinsky. Photo by Jim Block.

There are pivotal years in constitutional law: 1787, when the Constitution was ratified; 1791, when the Bill of Rights was adopted; 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was enacted; 1937, when the Supreme Court overturned 40 years of precedents that had limited the power of Congress and state legislatures to protect workers and consumers; 1969, when the liberal Warren Court ended, and the more conservative Burger Court began. And 2022 was such a decisive turning-point year.

The October 2021 term, which ended on June 30, 2022, was the first full term with all three justices appointed by President Donald Trump on the court. It was thus the first term in which a court had six conservative justices. And the impact was dramatic. A New York Times analysis, published after the term, said it was the most conservative year in the court since 1931.

For decade, conservatives have sought to overrule Roe v. Wade, limit the power of the administrative state and expand gun rights. They did all of this in a series of decisions between June 23 and June 30, 2022. Individually and collectively, these rulings show what it means to have a very conservative court. And these decisions do not end litigation on these issues, but rather are opening the door to countless new lawsuits to clarify their meaning and to try and expand their impact.

Abortion

Nothing has been more important on the conservative agenda for decades than the overruling of Roe v. Wade. It happened on June 24 in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Justice Samuel Alito, joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, wrote that Roe v. Wade was “egregiously wrong” and “exceedingly poorly reasoned.” The court expressly overruled Roe and said that the issue of abortion is left to the political process.

But Dobbs did not end litigation over abortion. Rather, it will lead to a myriad of new legal issues. For example, a federal law, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, enacted in 1986, requires Medicare-participating hospitals with emergency departments to screen and stabilize people experiencing health care crises. After Dobbs, the Department of Health and Human Services, issued a guidance letter that said that this includes providing abortions in certain circumstances, even when the state law would prohibit it. The guidance letter states: “When a state law … [draws an exception to an abortion prohibition] more narrowly than EMTALA’s emergency medical condition definition—that state law is preempted.” Many federal courts are now considering whether this federal law preempts state anti-abortion laws.

There are many other legal issues that are being litigated or sure to arise. For states that prohibit all abortions except to save the life of the woman, how is that to be defined and determined? Is it constitutional for a state to enact a law prohibiting importing into the state medications that induce abortions? Does it violate free exercise of religion for a state to prohibit abortions where a woman’s religion would require one? And as states adopt more laws restricting abortion, countless legal issues and lawsuits are sure to arise.

Second Amendment

On June 23, in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, the court declared unconstitutional a New York law, initially adopted in 1911, that prohibited having weapons in public without a permit. To secure that license, the applicant had to prove that “proper cause exists,” which New York courts interpreted to require that a person “demonstrate a special need for self-protection distinguishable from that of the general community.”

This was the first time in American history that the court said that there is a Second Amendment right to have guns in public, including concealed weapons. This would be significant in itself, but the court went further and prescribed the approach that courts are to use in evaluating gun regulations. The court rejected using the usual tiers of scrutiny, which focus on whether the government has an adequate purpose and whether the means are sufficiently related to the goal.

Instead, the court said that a regulation of firearms is allowed under the Second Amendment only if it was historically permitted. The court said it was not deciding whether the historical focus is just on 1791, when the Second Amendment was adopted, or whether it also includes 1868, when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified. Justice Thomas, writing for the majority in a 6-3 decision, stated: “To justify its regulation, the government may not simply posit that the regulation promotes an important interest. Rather, the government must demonstrate that the regulation is consistent with this nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation. Only if a firearm regulation is consistent with this nation’s historical tradition may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside the Second Amendment’s ‘unqualified command.’”

The court expressly rejected any balancing of the government’s interests in regulating guns with a claim of Second Amendment rights. Justice Thomas wrote “the Second Amendment is the very product of an interest balancing by the people and it surely elevates above all other interests the right of law-abiding, responsible citizens to use arms for self-defense.”

This raises the question of whether the court’s rejection of the levels of scrutiny and use of a purely historical test will be used in other areas of constitutional law. It also is leading to challenges to countless types of gun regulations.

For example, in September, a federal court issued an injunction against a Delaware law that prohibited the manufacture and possession of “ghost guns,” firearms without serial numbers. In October, a federal judge in West Virginia declared unconstitutional a federal law that prevents scratching out serial numbers on guns. Around the same time, judges in Texas struck down a federal law preventing those under indictment from having guns and a Texas law that prohibits 18- to 20-year-olds from carrying a gun in public. There are many challenges pending to federal and state laws preventing those with felony convictions from being in possession of guns.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court will need to clarify when and how the government can regulate guns in light of its decision in Bruen. But there will be hundreds of lower court decisions on a myriad of gun laws before that happens.

The administrative state

The court’s decision on June 30 in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency imposed a significant limit on the power of federal administrative agencies: the major questions doctrine. The court, in a 6-3 decision, held that the EPA lacked authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired power plants.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the court and explained that when there is a “major question” of economic and political significance, an administrative agency action is invalid unless there is clear direction from Congress. Justice Gorsuch, in a concurring opinion explained, “To resolve today’s case the court invokes the major questions doctrine. Under that doctrine’s terms, administrative agencies must be able to point to clear congressional authorization’ when they claim the power to make decisions of vast ‘economic and political significance.’ Like many parallel clear-statement rules in our law, this one operates to protect foundational constitutional guarantees.” The court concluded that the authority of the EPA to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired powerplants was a major question and that Congress had not provided sufficiently clear direction and authority.

But the court provided very little guidance as to how to determine what is a major question or what is sufficiently specific congressional direction to satisfy the doctrine. This opens the door to a myriad of challenges to administrative agency regulations of all sorts. In Biden v. Nebraska, which the court will hear in February 2023, the major questions doctrine is a crucial issue concerning the validity of President Biden’s student loan forgiveness program. In lower courts, the issue has been raised in matters such as the authority of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to issue a license for a private facility to store radioactive waste, the authority of the Department of Agriculture to expand its definition of sexual discrimination to include sexual orientation and gender identity, whether the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program is valid, and much more.

In conclusion

These, of course, are just three of the 58 cases decided by the court last term. There were other rulings that dramatically changed the law in a conservative direction and are spawning much litigation. For example, conservatives have long opposed the notion of a wall separating church and state, while wanting to aggressively protect free exercise of religion. In Carson v. Makin, on June 21, the court held that Maine violated free exercise of religion when it paid for some students to attend secular private schools but would not allow the funds to be used in religious schools. In Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, on June 27, the court ruled that it violated free exercise of religion and freedom of speech to discipline a high school football coach for engaging in silent prayers on the field after games. Both cases have opened the door to many suits in the lower courts.

Most of all, it is important to see 2022 as an extraordinary year in the Supreme Court. It is the culmination of what conservatives have sought for a half century. And it is surely the harbinger of what is to come.

Erwin Chemerinsky is dean of the University of California at Berkeley School of Law and author of the newly published book A Momentous Year in the Supreme Court. He is an expert in constitutional law, federal practice, civil rights and civil liberties, and appellate litigation. He’s also the author of The Case Against the Supreme Court; The Religion Clauses: The Case for Separating Church and State, written with Howard Gillman; and Presumed Guilty: How the Supreme Court Empowered the Police and Subverted Civil Rights.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.