Justice Stevens' papers let researchers peek into Supreme Court's inner workings

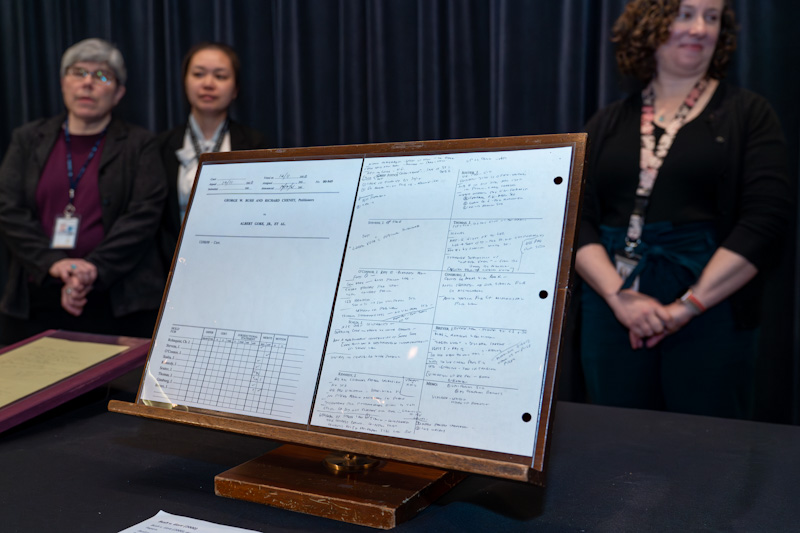

Papers of the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens, including his notes during Bush v. Gore, were made available to researchers at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., on May 1. Photo by J. Scott Applewhite/The Associated Press.

In 2001, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote the opinion for a U.S. Supreme Court majority holding that the PGA Tour had to allow a golfer with a degenerative circulatory disorder to use a cart despite a rule requiring that competitors walk during the third stage of the qualifying tournament.

Stevens, an avid golfer who practiced putting on the carpet in his chambers, seemed to relish the case, PGA Tour Inc. v. Martin. It involved rising competitor Casey Martin, whose affliction obstructed the flow of blood from his right leg back to his heart, making it painful for him to walk.

According to case files in the 741 manuscript boxes full of Stevens’ papers newly opened to the public this month by the Library of Congress, Stevens had to take some extra strokes to preserve his tentative 7-2 majority and to keep it from being saddled with concurrences.

Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote to Stevens on March 9, raising several points about the “difficult” case. He had concerns with Stevens’ view in a draft majority opinion that a waiver of the walking rule would not be a “fundamental alteration” of the game because Martin ends more exhausted than his competitors even if he uses a cart.

“At conference I expressed some initial agreement with you on that point, but then thought there was some consensus in the majority that this might lead us into a morass involving head starts for runners, etc.,” Kennedy wrote. He urged Stevens to drop the point and focus on the more general view that the introduction of a cart was not a fundamental alteration of golf’s rules.

Stevens responded March 12, pushing back on Kennedy’s argument.

“I don’t think there is any risk that the opinion will be read as requiring head starts for runners,” Stevens said. Such an advantage wouldn’t be necessary for a runner with a disability merely to participate in a race, he said, while Martin required a cart to compete in a golf tournament.

“Moreover, surely the length of each race is fundamental in a track meet just as shot-making is fundamental in golf,” Stevens said. “The no-cart rule is peripheral at best.”

One of 38 justices at the Library of Congress

Stevens was nominated to the court by President Gerald Ford in 1975 and retired in 2010.

“We’re very proud to be the home of the Justice Stevens’ papers because he was a consequential member of the U.S. Supreme Court for decades and a leading voice on so many important and historic cases,” said Librarian of Congress Carla D. Hayden at a May 1 press conference.

The papers give researchers and others a window on the inner workings of the court, especially in the period from 1994 through the summer of 2005. Justice Harry Blackmun, who served from 1970 to 1994, kept very comprehensive files, including the many memos in each case that were typically copied to “the conference”—all the members of the court.

Thus, many of Stevens’ early files cover ground that has been explored in the Blackmun papers or those of Justice Thurgood Marshall.

In 2020, the Library of Congress opened a first portion of Stevens’ papers, covering 1975 to 1984. But that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, and access was limited. The new portion covers the 1984-85 term through the 2004-05 term. Stevens, who died in 2019 at age 99, specified that the files from his last five terms on the court, 2005-06 to 2009-10, not be released until 2030.

“We first solicited Justice Stevens’ papers in 1980,” said Janice E. Ruth, the chief of the library’s manuscript division. “That’s not uncommon. We will be soliciting papers long before we get them and [spend] many decades, sometimes, building a relationship.”

The Library of Congress has the papers of 38 jurists who served on the Supreme Court, including those of retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, though those justices’ files are not yet open.

Trying to steer clear of ‘center ring of partisan politics’

With the new batch of Stevens papers, some journalists and researchers went immediately to a couple of big, politically tinged cases—Bush v. Gore, the decision that effectively decided the 2000 presidential election in favor of George W. Bush; and Clinton v. Jones, the 1997 case in which the court rejected President Bill Clinton’s efforts to defer proceedings in a sexual harassment civil suit until after he left the White House.

The Bush v. Gore file provides some fresh insights but no shocking revelations about the court’s deliberations in the historic 5-4 case in which Stevens was a dissenter.

“I think the previously agreed upon deadline of one o’clock this afternoon for release of the opinions is unrealistic,” Rehnquist wrote to his colleagues on Dec. 12 as the court raced to resolve the case the day after it was argued. In a later memo that day, Rehnquist pushed the deadline to 6 p.m. “I am unwilling to move the deadline further back unless there is some sort of a mechanical breakdown,” he wrote. (The decision was released to the public after 9 p.m. ET that day.)

Scalia ended the day with a memo to his colleagues criticizing the tone of the dissents in the 5-4 decision, arguing that those justices who were arguing the decision would do “irreparable harm” to the court “have spared no pains … to assist that result.”

“I am the last person to complain that dissents should not be thorough and hard-hitting,” Scalia wrote. “But before vigorously dissenting … I have never urged the majority of my colleagues to alter their honest view of the case because of ‘potential damage to the court.’ I just thought I would observe the incongruity. Good night.”

In the 1997 Clinton v. Jones case, Stevens wrote the decision for a unanimous court, but not before he dealt with concerns from his colleagues, including about its partisan implications.

“This case is in the center ring of partisan politics (circus is the proper analogy), and it is of course crucial that we not appear to be taking political sides,” Justice Antonin Scalia wrote to Stevens April 4. He worried that parts of Stevens’ draft opinion meant that the court was doing the White House press secretary’s “job for him.”

Stevens wrote back to Scalia on April 8, saying he would “tone down” some passages. “I do believe, however, that it is appropriate to make it clear that we regard the arguments put forth on behalf of the president as serious submissions, and not just a gimmick to stall the case until after the election,” he wrote.

Stevens’ files also include an example of a more guarded exchange between two justices, one not shared with all their colleagues.

In Grutter v. Bollinger in 2003, the court ruled 5-4 to uphold the race-conscious admissions plan of the University of Michigan Law School. As the case was being deliberated, Stevens wrote privately to Justice David Souter to urge him not to add a short concurrence to O’Connor’s majority opinion.

“It seems to me that your separate writing, though brief, diminishes the force of Sandra’s powerful opinion,” Stevens wrote, adding that “on balance we have a really great victory” in the higher education case. Souter agreed to drop the concurrence.

Golf case prompts multiple reactions

The PGA Tour argument came up just over a month after the bruising Bush v. Gore case.

Stevens had been a particularly active questioner during oral argument in the golf case. One of his law clerks tracked down some obscure information on how players qualify for the U.S. Open and how the golf-handicapping system operated.

“This is most likely more than you’ll need for the opinion, but I thought it would be of interest to you as a golfer,” the clerk wrote to Stevens. The justice did refer to the handicap system for scoring in his opinion, and he cited the first known published rules of golf, from Scotland in 1744.

In the end, the court ruled 7-2 that the Americans with Disabilities Act prohibited the PGA Tour from denying access to its tournaments on the basis of golfer Casey Martin’s disability, and that allowing Martin to use a cart would not “fundamentally alter the nature” of the tour.

Scalia, joined in dissent by Justice Clarence Thomas, mused that the majority opinion might lead the parents of a Little League baseball player with attention deficit disorder to sue to seek four strikes per at-bat for their child instead of three.

Stevens kept a reaction letter sent the day after the decision was issued on May 29 that made a similar point.

“I suppose in the NBA, the league should offer ladders so short people can dunk,” the writer observed. “After the presidential decision, and now this, I am losing confidence in the U.S. Supreme Court.”

But Stevens may have taken heart from a note from Kennedy, with whom he had traded memos on the fine points of the draft opinion for more than a month before Kennedy finally agreed to withdraw his proposed concurrence.

“You have at least a birdie, maybe even an eagle,” Kennedy wrote of Stevens’ opinion.

See also:

ABAJournal.com: “Rehnquist dropped push for ‘independent state legislature’ theory in Bush v. Gore, Stevens’ papers show”