Trump and his 3,500 suits: Prosecutor and author reveals in interview his portrait of 'Plaintiff in Chief'

President Donald Trump. Photo from Shutterstock.com.

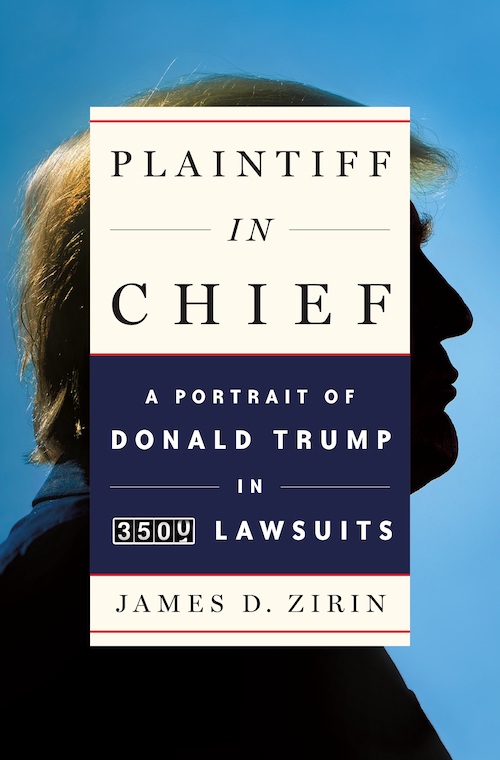

While Donald Trump had no experience in working in government or in public service when he became president of the United States, he brought an astounding history of involvement in thousands of lawsuits to the nation’s highest office. Former federal prosecutor and author James D. Zirin illuminates more than 45 years of Trump’s legal disputes in his new book, Plaintiff in Chief: A Portrait of Donald Trump in 3,500 Lawsuits, published in September 2019.

As a federal prosecutor, Zirin spent decades handling complex litigation. He’s also a self-described “middle-of-the-road Republican.” Plaintiff in Chief is not a partisan screed but a carefully documented legal study.

In his book, Zirin scrupulously details Trump’s life in courts of law. Based on more than three years of extensive research, the book examines illustrative cases and how they reflect on the character and moral perspective of the current president. Zirin references page after page of court records and other evidence to illustrate Trump’s legal maneuvering.

As Zirin points out, Trump learned how to use the law from his mentor, notorious lawyer Roy Cohn. Trump took Cohn’s scorched-earth strategy to heart.

“Trump saw litigation as being only about winning,” Zirin writes. “He sued at the drop of a hat. He sued for sport; he sued to achieve control; and he sued to make a point. He sued as a means of destroying or silencing those who crossed him. He became a plaintiff in chief.”

Zirin argues that Trump has shown a chronic scorn for the law. “All this aberrant behavior would be problematic in a businessman,” he writes. “But the implications of such conduct in a man who is the president of the United States are nothing less than terrifying.”

Zirin is an accomplished litigator who has appeared in federal and state courts around the nation. He was an assistant U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York under then-U.S. Attorney Robert M. Morgenthau.

His other books include Supremely Partisan: How Raw Politics Tips the Scales in the United States Supreme Court and The Mother Court: Tales of Cases That Mattered in America’s Greatest Trial Court. His articles have appeared in array of publications.

Zirin recently answered some questions—from Robin Lindley, a Seattle-based writer and lawyer—on his study of Trump, by telephone from his office in New York.

Robin Lindley: In your book, you chronicle Donald Trump’s life as a litigator for almost a half-century. How did you come to write Plaintiff in Chief on Trump’s life through more than 3,500 lawsuits?

James Zirin: About three years ago, a friend suggested that I write a biography of Roy Cohn. I knew Roy Cohn. He was an unscrupulous lawyer. He was disbarred 1986, about three years before he died. And he was Trump’s lawyer and confidant, and their relationship was very close, very intimate. He boasted to a journalist that he and Trump spoke about five or six times a day. This was before Trump had any notion of seeking political office.

Cohn really taught Trump everything he knows about waging what I call asymmetrical warfare, weaponizing the law and using litigation as a means to attain the various objectives that he had. They met in a bar in 1973 just after Trump had been named as a defendant along with his father in a race discrimination in housing suit brought by the Justice Department. Trump had a number of lawyers, and normally a suit like that ends quickly with a consent decree with the defendant agreeing that he or she won’t discriminate anymore without accepting or admitting or denying the allegations in the complaint.

Cohn had a different recipe for going forward. He liked to beat the system. He’d been indicted three times by the legendary prosecutor Robert M. Morgenthau, and he’d been acquitted three times. Cohn’s recipe was fight, and he taught Trump the tools he used. No. 1 is if you’re charged with anything, counterattack. Rule No. 2 is if you’re charged with anything, try to undermine your adversary. Rule No. 3 is work the press. Rule No. 4 is lie. It doesn’t matter how tall a tale it is, but repeat it again and again. Rule No. 5 is settle the case, claim victory and go home. And that’s exactly what happened in the race discrimination case.

So, anyway, I created a book proposal, which I sent to my agent and my publisher, St. Martin’s Press. In its wisdom, the press said I should try to write a larger book about the influence of litigation on Donald Trump because that’s the way he had conducted himself in the 40 years before he achieved office, and I should use Cohn perhaps as a springboard, but the book should center on Trump and what experience he had had in litigation. So I did that, and that’s how I came to create the book.

Robin Lindley: It’s a remarkable and chilling account of Trump’s life through the prism of his legal affairs. You stress in the book that the two most powerful influences in his life were Roy Cohn and his father, Fred Trump.

James Zirin: Yes. His father, of course, was a defendant, as well, in the race discrimination cases. His father was also a real estate operator, and he came up against the government in the arena of FHA loans. He was accused of profiteering. He testified before a Senate committee and was interrogated by Sen. [Herbert] Lehman. He made a lot of money by mortgaging out with FHA loans in ways that they were never intended. Then when he was asked about the profits, he said he had never withdrawn the money from the bank, so therefore there were no profits. That was ridiculous. But here is an example of saying something that’s totally ridiculous for public consumption that somehow or other some people will believe. And that’s the approach Trump has used professionally, and that’s the approach he continues to use in office.

Robin Lindley: Were you ever involved in litigation with Donald Trump?

James Zirin: No. I never was. I met him several times, and I met him with Roy Cohn several times. When I first met Cohn, I was an assistant U.S. attorney and Cohn was being investigated by a federal grand jury. I worked for Robert M. Morgenthau then, and that investigation resulted in indictments. Cohn was in the anteroom of the grand jury chamber and witnesses were waiting to testify, and he raised his open hand in what might be interpreted as a high five. I naively thought it was a high five to encourage the witnesses since they were facing the daunting experience of testifying before a grand jury. And it wasn’t the high five at all. He was telling them to take the Fifth [Amendment].

That’s how Cohn operated, and that’s the way Trump operates. It’s saying something that’s highly incriminating and doing something that’s highly incriminating but doing it in a way so that you have total deniability if anyone calls you out for it.

Robin Lindley: What was your impression of Trump when you met him decades ago?

James Zirin: I really met him only to shake hands. I never met him to talk with him, but I knew of his reputation. I knew he didn’t pay his bills. I knew he didn’t pay his lawyers. I knew he’d been in bankruptcy five times, and I knew about his Atlantic City casinos. I knew he’d been sued a number of times. And I knew that he had been a plaintiff an extraordinary number of times. He sued journalists. He sued small businesspeople for using the Trump name. He sued women who he was involved with. He sued his wives even after a divorce, both Ivana and Marla Maples. And I knew that a lot of settlements he entered during litigation were kept under seal in the files of the court, so the public would never know the terms of the settlements.

In one major litigation effort, you had the so-called Polish brigade case, which involved the construction of Trump Tower that opened in 1983. Trump had undocumented Polish workers, and he did not contribute to the union pension fund as he was required to do. There was litigation, and it was eventually settled for 100 cents on the dollar after lengthy litigation, including a trial in which the trial judge said Trump’s testimony was completely lacking in credibility. But the case was settled. We never knew what the terms of settlement were; except, about 20 years later, a judge unsealed the settlement papers, and it turned out that Trump had settled for 100 cents on the dollar.

Robin Lindley: Readers may be surprised that you’re a Republican.

James Zirin: I’m actually a lifelong Republican, and I’m decidedly anti-Trump because I don’t think he represents the values of the country or the Constitution of America. I think he’s been a rogue president.

Robin Lindley: A lot has happened since your book came out, with Trump’s reaction to the Mueller report, his impeachment, his [use] of the Department of Justice, and more suits against the media and others. And Trump continues to follow the Cohn rules. Trump famously said he needed a Roy Cohn. Does he have his Roy Cohn now in William Barr, the attorney general?

James Zirin: Many people have suggested that. I think Barr is more of an ideologue. He’s not an unscrupulous lawyer as Roy Cohn was. Roy Cohn represented mobsters, and he was a crook. He was eventually disbarred because he stole $100,000 from a client. He was disbarred because his yacht went up in flames, and a crew member was killed. He collected the insurance. It was supposed to go to his creditors, but instead he pocketed the money. He was disbarred because he made a false and misleading statements on an application to become a member of the D.C. Bar, and there was a disbarment hearing. Trump was one of a number of his character witnesses, and he testified to Cohn’s good reputation for honesty, integrity, truth and veracity. And, of course, Cohn’s reputation for honesty, integrity, truth and veracity was very bad.

And after Cohn was disbarred in 1986, Trump distanced himself from Cohn, but that was not for long because Cohn died three weeks thereafter. There was a funeral, and Trump stood in the back of the room and delivered no eulogy and never said much more about him.

What we do know about how close the relationship is that 30 years later, in 2016, when Trump was elected president, he turned to gossip columnist Cindy Adams, a friend of his, and he said, “Cindy, if Roy were here, he never would’ve believed it.” So we know that’s how close the relationship was. And in the White House in 2017, when counsel Donald McGahn was dragging his feet about firing [then-U.S. Attorney General Jeff] Sessions, Trump made the famous statement, “Where’s my Roy Cohn?”

Robin Lindley: Trump continues to bring lawsuits from the White House. In the last couple of weeks, he has sued the New York Times and CNN for defamation. Of course, he’ll never appear to be deposed, so those lawsuits will probably go nowhere. You chronicle that sort of [use] of the legal system for the last 45 years or so.

James Zirin: That’s right. He has sued a lot of writers. Before he took public office, he sued the journalist Tim O’Brien for daring to write that his net worth was overstated. They took his deposition, and he demonstrably lied at least 32 times under oath, and the case was eventually dismissed. The defense was able to show the truth that, in fact, he had overstated his net worth. That was one of Trump’s sore points, and he sued whenever someone said he was worth less than he believed should be stated. But O’Brien won his case.

And he brought other cases against journalists. He sued an architectural critic for the Chicago Tribune for suggesting that one of his buildings, which wasn’t even up but was planned, would be an eyesore on the horizon. The judge threw the case out because of the rule of opinions. To succeed in a libel action, you have to show that a statement of fact, which is defamatory and false, was made of and concerning the plaintiff. The architect stated an opinion that the building would be an eyesore on the horizon, and that’s not something that could ever be libelous.

Robin Lindley: You use the term truth decay. How does [Trump’s] pattern of lying fit into his attitude toward the law?

James Zirin: I think he enjoys lying. I think it’s part of his DNA. I don’t think he has any grasp of the facts at all, so he says whatever he thinks will help him and whatever comes into his head. It is expedient, I suppose, to lie in litigation if you crossed an intersection through a red light. You can lie and say it was a green light, and that changes the legal outcome of your case. And that’s the way Trump operates. But he would go beyond that because he would say the heck with you and the horse you rode in on as he did in the House impeachment inquiry. Then he denounced Adam Schiff and denounced Jerry Nadler and denounced the witnesses. He tried to subvert the whole proceeding by denouncing the whistleblower and by showing that those people who lined up against him were of low character and were themselves liars.

All of this goes back to Joe McCarthy because this is the way McCarthy operated. Then adversaries accused McCarthy of engaging in a witch hunt and accused McCarthy of generating these hoaxes. And, of course, Roy Cohn was McCarthy’s chief counsel. And so he learned how useful those charges can be and how devastating they can be in any kind of controversy. And he taught all of that to Trump, and Trump uses that to his great advantage.

James D. Zirin. Photo by Julie Skarratt.

James D. Zirin. Photo by Julie Skarratt.

Robin Lindley: You write that power and dominance are even more important to Trump than money. And he seems to take joy in attacking and ruining anyone he perceives as a foe of some sort.

James Zirin: Well, that’s true. In one of the cases that I describe in the book, he got wind of the fact that a small business, a travel agency conducted by father and daughter in Baldwin, Long Island, was using the name “Trump Travel.” Not Donald Trump Travel but Trump Travel. They used Trump Travel because they were selling a bridge tour for people who play bridge, and “trump” is a bridge term. Also, like “Ace Hardware,” they thought “Trump” keynoted excellence. This was a little storefront travel agency in a small Long Island community. Trump had never been in the travel business and he never had any business involvement in Long Island, but he sued them. And at the end of the day, they were allowed to continue to use the name Trump Travel, but it had to make the lettering a little smaller. And they’d exhausted their life savings in defending the case. So he was quite sadistic about the way he went about it.

There was another similar case where an unrelated family named Trump from South Africa had a multibillion-dollar pharmaceutical business, and Trump sued them. He’d never been in the pharmaceutical business and had never been in business at that point anywhere outside the United States. But this family had the wherewithal to defend the case, and eventually the case was thrown out completely.

Robin Lindley: Since the book came out, have you received any backlash or criticism from Trump supporters or Republicans?

James Zirin: No. I’m often asked if I expect Trump to sue me, and I say I wish he would because it would help the sales of the book. The book Fire and Fury would have sold about 5,000 copies, but then when Trump tried to enjoin it, it was like “Banned in Boston” and it became a runaway bestseller and sold 3 million books. I haven’t received any backlash because the book is very well documented, and everything in it is true, but the response [from Trump supporters] is basically, “So what?”

Robin Lindley: Do you have any words of wisdom now on the future of democracy and the rule of law and Trump’s persistent pattern of using the law to his ends?

James Zirin: He has continued, and I think he will continue. And I think the rule of law has been seriously undermined. Our democracy has been seriously compromised because the framers of the Constitution never thought the system would work this way. Republican senators deserve part of the blame because of their need to retain power or whatever, they did not respect the oath they took to be fair and impartial judges of the facts and the law but instead voted along party lines to acquit him [during the impeachment trial].

Robin Lindley: As you illustrate, Trump is an anomaly in terms of the adversarial system. Do you have anything to add on his use of legal process?

James Zirin: Look, the adversary system is the crown jewel of our legal system. We got it from the British. The idea is that you had lawyers on both sides who were partisan, who were like the Knights Templar who rode into battle on behalf of somebody or other in the Middle Ages. That has been the best way of getting at the truth. In contrast, in civil law countries, like France or Germany, the judge conducts the inquiry. The judge might ask questions of the lawyers, but the lawyers don’t develop the evidence on both sides.

But adversary doesn’t mean enemy. What Trump has demonstrated is that we have a great legal system, and we all have the benefit of it. But there are also limitations for the law, and those limitations can be exploited by someone determined to beat the system, and that’s what Trump has done.

Robin Lindley is a Seattle-based writer and lawyer. He is the features editor for the History News Network, where a version of this interview first appeared. Lindley’s work also has been featured in the Writer’s Chronicle, Crosscut, Documentary, NW Lawyer, Real Change, the Huffington Post, BillMoyers.com, Salon.com and more. He has a special interest in the history of human rights and conflict. He can be reached by email at [email protected].