Show Me Your ID: Cops, Courts Re-evaluate Their Use of Eyewitnesses

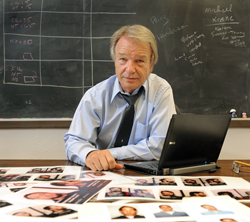

Gary Wells of Iowa State University has studied problems with police lineup procedures for 35 years. He says that the progress made in the past few years has been remarkable, “like a runaway train.” Photo courtesy of Gary Wells.

After more than three decades of laboratory studies, experts have found that a few simple changes in police lineup procedures improve the accuracy of eyewitness identifications.

For example, having someone administer the lineup who doesn’t know who the real suspect is can prevent inadvertently influencing the witness’s pick. And telling the witness that the perpetrator may not be present in the lineup lessens the chances that the witness will feel compelled to identify a suspect.

Police departments have been reluctant to act on the recommendations. But that is changing. One-quarter to one-third of all police departments now use the double-blind, sequential approach, according to some estimates, and their ranks appear to be growing every day.

Two states—New Jersey and North Carolina—require that all lineups be conducted sequentially and using a double-blind method, where the administrator does not know which person is the suspect. So do many local law enforcement agencies, including some of the nation’s biggest police departments.

MUCH PROGRESS

Gary Wells, an Iowa State University psychology professor who’s been studying problems with police lineup procedures for 35 years, says the progress made in the past few years “seems like a runaway train” compared with what he witnessed during the first 30.

In the past year:

• Texas became the 10th state to pass a law requiring police departments to adopt written lineup procedures designed to reduce the risk of faulty identifications.

• The New Jersey Supreme Court issued a landmark ruling on the use of eyewitness identification evidence at trial.

• A new field study of police lineup procedures confirms what scientists like Wells have long been saying.

• And the U.S. Supreme Court heard its first case on eyewitness identification evidence in 34 years.

“We still have a long way to go,” Wells says, “but we’re definitely making headway.”

Last June, Texas joined nine other states in enacting legislation requiring all local law enforcement agencies to adopt written procedures addressing such things as who should administer the lineup and what kind of instructions the witness should receive. At the time, 88 percent of those agencies had no written procedures for conducting lineups. The written policies must be adopted by Sept. 1.

That Texas, known as a strong law-and-order state, has reformed its lineup procedures should help persuade other jurisdictions, Wells and other reform advocates say. “If we can get that kind of reform in Texas,” Wells says, “we can get it anywhere.”

The Texas legislation was followed in August by a landmark New Jersey Supreme Court ruling laying out sweeping changes in the way eyewitness ID evidence is handled at trial.

Click here to read the rest of “Show Me Your ID” from the May issue of the ABA Journal.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.