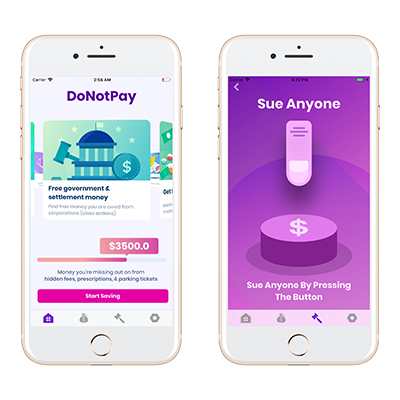

DoNotPay app aims to help users sue anyone in small claims court--without a lawyer

Images courtesy of DoNotPay.

Updated: A new update to an existing chatbot app promises to allow users to "sue anyone in small claims court for up to $25,000 without the help of a lawyer," though early users warn of technical bugs and legal and ethical concerns.

Launched Wednesday, new updates to DoNotPay, a company that first made a splash by automating challenges to parking tickets in court without an attorney, will allow a user to sue anyone in small claims court in any county in all 50 states—without the need for retaining a lawyer. Previously only a web tool, the new product is also available for iPhone and will also include new features allowing users to find deals on prescription and over-the-counter drugs; make an appointment at the California Department of Motor Vehicles; and see if they are eligible to opt-in to various class-action settlements. The app also aims to fight unfair bank fees; earn refunds from ride-hailing companies; fix errors in a credit report; and dispute bank transactions.

An Android version is in the works.

“I want people to be addicted to fighting for their rights,” says Josh Browder, CEO of DoNotPay, who hopes his revamped app will be a one-stop shop for consumer protection issues.

The idea for the new app was born out of a project the company released last year, which helped people sue Equifax for up to $25,000 after the credit company’s 2017 data breach affecting 143 million people.

“Although lots of lawyers said it wasn’t possible,” said Browder in a statement reported by Yahoo Finance, “I was shocked when people won $9,000, $10,000 and $11,000 judgments. Even when Equifax appealed, the average person still prevailed.”

The new small claims suit feature, which Browder demoed at the Clio Cloud Conference last week in New Orleans, asks a user for their name and address and what the claim size is to determine whether it complies with a state’s limit, among other factors. It then generates a demand letter, creates a filing, helps serve notice of the suit and provides other support to usher users through the trial process. The app even generates suggested scripts and questions pro se litigants can use when they go to court. Parties are often not represented by an attorney in a small claim proceeding because it is either not permitted by law or because the amount in controversy is too low to justify the cost of an attorney.

Browder says the new application has three goals: Getting users what’s owed, fighting corporations and fighting bureaucracy.

Not just a small claims app, DoNotPay acquired Visabot to assist in the application of green cards and other visa applications. Previously, Visabot charged for many of its services (a green card application was $150, for example). All features on DoNotPay, including immigration, are free to users.

This isn’t to say that the new app won’t make money. While the revenue model is still a work in progress, Browder sees a future where after helping someone challenge a cellphone bill, they offer deals to switch carriers and take a commission based on conversions. While the app will require extensive user data to function, Browder says the venture-backed DoNotPay will not store or sell user data.

Of course, many of these features raise the specter of the unlicensed practice of law, a criminal offense in California, where Browder is based.

For his part, Browder is “a bit worried” about potential challenges. However, he believes that he can avoid some of these issues since his product is free to users. Further, he argues that the app is a free speech issue because its underlying code is speech. Code has been found to be speech on issues as broad as publishing encryption source code to the sharing of digital blueprints of 3-D printed guns.

“If you can 3-D print a gun,” he says, “you should be able to print a few documents.”

The legal profession is only one possible group to take issue with the new tool—the other are the users themselves. While the automated process was set up with the assistance of lawyers and paralegals, there’s no lawyer oversight of the app’s final products.

Asked how users should manage their dissatisfaction towards the product, Browder says it’s easy. “They can sue us with the app.”

In the day after the app’s release, several Twitter users took issue with technical and legal aspects of the tool. Nicole Bradick, a 2012 ABA Journal Legal Rebel, noted that the tool did not work properly. Gabriel Teninbaum, director of Suffolk University Law School’s Institute on Legal Innovation & Technology in Boston, said that he was given bad, inaccurate advice on Massachusetts law. Chase Hertel, counsel and deputy director for the ABA Center for Innovation, expressed concerns that the immigration feature did not fully inform people of various ongoing and evolving issues.

For his part, Browder says DoNotPay has pushed numerous updates to handle some of the technical issues.

Regarding the immigration feature, Browder defends it as the same tool it was before acquisition, which had “extremely positive reviews.” He adds that “we not only plan to maintain it, but also expand it.”

“While I can understand the skepticism of the legal establishment, I worked with public defenders in [Massachusetts] in detail to ensure it’s accurate,” says Browder over email regarding criticisms coming from Massachusetts. “Accuracy is an objective term and not opinion. Unless they can point to a precise and specific contradiction between the demand letter [DoNotPay] provides and [Massachusetts] law, it is false and defamatory to suggest it’s inaccurate.”

Updated on Oct. 11 after the app’s launch to add details about the issues users were reporting and Browder’s response.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.