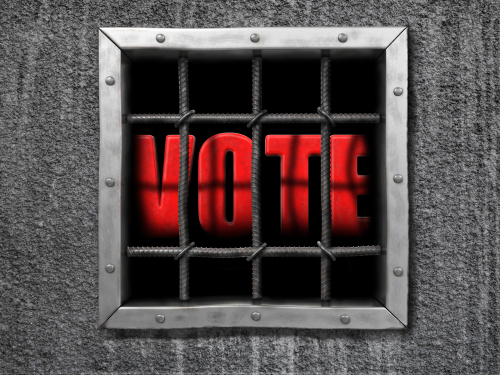

In states where inmates can vote, few exercise their right to cast ballots

Image from Shutterstock.

When Sen. Bernie Sanders championed voting rights for prisoners during a CNN town hall, he spotlighted an intensifying national debate about why going to prison means losing the right to vote.

In only two states, Maine and Vermont, all prisoners are eligible to vote. However, some prisoners in Mississippi, Alaska and Alabama can vote while incarcerated, depending on their convictions. Sanders is the sole presidential candidate to support the idea of prisoners voting, regardless of their crimes. His stance may reflect the reality that his home state of Vermont, and its neighbor Maine, have long-established procedures, and general public acceptance, of people voting from behind bars.

The idea is percolating in other states, however. In June, six of the 13 council members in Washington, D.C., endorsed legislation that would let the city’s prisoners vote. Legislators in Massachusetts, Hawaii, New Mexico and Virginia introduced measures to allow prisoners to vote earlier this year. None succeeded, but several others states are making it easier for people to vote once they leave prison. In May, Nevada’s governor signed a bill that automatically restores voting rights for parolees. And, last year, voters in Florida re-enfranchised nearly 1.5 million residents with felony convictions while Louisiana restored voting rights for nearly 36,000 people convicted of felonies. Lawmakers are still considering similar proposals in Connecticut, New Jersey and Nebraska.

Still, most prisoners lose the right to vote while incarcerated. Roughly 15 states automatically restore voting rights upon release, but several states such as Alabama and Mississippi ban people from voting for life for some crimes.

The exceptions

Why are Vermont and Maine outliers? They share several characteristics that make voting by prisoners less controversial. Incarcerated people can only vote by absentee ballot in the place where they last lived. They are not counted as residents of the town that houses a prison, which means their votes can’t sway local elections if they vote as a bloc. And unlike many states, the majority of prisoners in Maine and Vermont are white, which defuses the racial dimensions of felony disenfranchisement laws.

Laws barring people with felony convictions from voting first began cropping up in Southern states during the Jim Crow era. Many voting rights advocates say the laws were a deliberate attempt to limit black political power. Of the nearly 6.1 million people estimated to be disenfranchised because of a felony conviction, nearly 40 percent are black, according to a 2018 report by the Sentencing Project.

Joseph Jackson, founder of the Maine Prisoner Advocacy Coalition, suspects the racial demographics in Maine and Vermont may account for the fact that prisoners in either state never lost the right to vote. In Maine and Vermont, black people represent a larger share of prisoners compared with their share of the general population, but are a minority of the state’s prisoners overall, nearly 7 and 10 percent respectively.

In Maine and Vermont, the state constitutions guarantee voting rights for all citizens, interpreted to include incarcerated people from the earliest days of statehood (in Vermont, a legal decision dates from 1799). Past attempts to exclude those convicted of serious crimes have failed in the legislatures. Currently, there is no organized opposition in either state to voting from prison.

Corrections officials in both states encourage inmates to vote, but rely on volunteers to register inmates. In recent election years, voting advocacy organizations such as the League of Women Voters and the NAACP have coordinated with corrections departments to hold voter registration drives in the prisons. To bridge the information gap, they share one-pagers with information about the state candidates and explain their positions on key issues.

Yet the barriers to voting, both external and internal, remain high. Incarcerated people are restricted from using the internet and often cut off from news in the places they used to live. They are not allowed to campaign for candidates, display posters or show other signs of political partisanship.

Experts and volunteers who try to encourage voting from prison suspect that very few actually exercise the rights they have. Neither corrections department tracks inmate voting or registration, so statistics on participation or the political ideologies of prisoners are unavailable. Because their votes are counted along with other absentee ballots, election officials in Maine and Vermont do not specifically tally how many incarcerated people vote.

Polarized politics

For John Sughrue, the law librarian at Southern State Correctional Facility in Vermont, voting is imperative, the only “effective tool” inmates have for bringing change to the prison system. Yet, he notes, only a tiny percentage of the people in the prison where he is incarcerated end up voting. Among the few interested in politics, discussing issues can be dangerous in prison; as in the rest of the country, liberal and conservative inmates are increasingly polarized.

“It seems the current political climate has rendered us inexorably divided,” he wrote via the prison email system.

But the biggest issue, Sughrue says, is the shockingly high illiteracy rate among Vermont’s prisoners. In helping people with their legal cases, Sughrue realized many can’t read, and even those who can read struggle to write, which makes registering to vote and filling out a ballot practically impossible without help. The corrections departments don’t track literacy rates among prisoners, but in Vermont officials estimate nearly 20 percent of inmates entered prison with less than a high school education. Some studies estimate nearly 60 percent of people in prison are illiterate.

Despite volunteers’ efforts to engage incarcerated voters, many inmates in Vermont don’t seem particularly interested, said Madeline Motta, who helped register Vermont prisoners in 2018. Motta says some of the inmates were surprised to find they could vote, assuming their felony conviction was an automatic disqualifier. Others were more cynical, and expressed a general distrust of anyone seeking public office. A handful felt as if there was no point. Motta and the other volunteers tried to explain the benefits of voting during registration drives.

“We explained to inmates that elected officials are making decisions about your quality of life while you are incarcerated and once you are out,” she said.

Motta estimates several dozen men registered to vote between the two prisons she visited, which house roughly 500 prisoners. Other volunteers had already registered some inmates, so even her count was inexact. In Maine, Jackson estimates the NAACP registered more than 200 voters last year, but he can’t say how many actually voted.

Before the 2018 midterms, Kassie Tibbott traveled to five of Vermont’s prisons registering voters. Tibbott runs the Community Legal Information Center at the Vermont Law School. She said she heard very little political chatter during her visits, but a handful of prisoners were buzzing over a state attorney race in Bennington. Tibbott recognizes that a lack of access to information may be partly to blame. Inmates can’t go online to research candidates. Many watch television and listen to the radio, but may not tune into the news.

“They don’t know enough about the candidates, so why would they vote?” she asked.

Apathy in general

Voter disaffection is hardly unique to prisoners, said Paul Wright, executive director of Prison Legal News. Sixty-one percent of all eligible voters cast a ballot in the 2016 presidential election, and in the 2018 midterms, usually a time of lower turnout, that number dropped to 49 percent, according to Pew Charitable Trusts.

Wright suspects that some of the apathy about voting stems from the relatively few candidates with track records on criminal justice that would appeal to incarcerated people or those with raw memories of encounters with police and prosecutors.

At the local level, he pointed out, officials who play a major role in shaping criminal justice outcomes such as sheriffs, judges and prosecutors often run unopposed or on tough-on-crime platforms. Progressive prosecutors are a relatively recent phenomenon. So, like disaffected segments of the general electorate, inmates may believe their votes will make little difference.

“We don’t have much of a democracy when it comes to candidate choice,” he said. “Making the conscious choice in refraining from exercising your rights is just as important as exercising them.”

This article was originally published by the Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for the newsletter, or follow the Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.