Can Rudy Giuliani rely on attorney-client privilege to avoid congressional testimony?

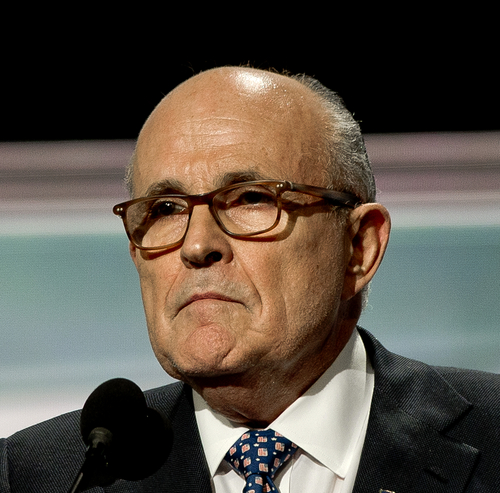

Rudy Giuliani, President Donald Trump’s personal lawyer, in July 2016. Photo from Shutterstock.com.

Rudy Giuliani, President Donald Trump’s personal lawyer, has suggested that he is protected by attorney-client privilege in the impeachment inquiry by Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives. But at least one expert takes issue with that assertion.

House Democrats subpoenaed Giuliani on Monday, report the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times. They want Giuliani to provide documents to three House committees by Oct. 15 concerning efforts to get Ukraine to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden and his son, Hunter, a paid board member with a Ukrainian gas company.

The committees are seeking information in connection with Trump’s bid to get Ukraine to investigate whether Biden stopped a Ukrainian investigation of the gas company. In a Sept. 30 letter to Giuliani, the committee chairs said they are investigating allegations that he aided Trump “in a scheme to advance his personal political interests by abusing the power of the office of the president.”

On Sunday, Giuliani reminded Fox News that he is an attorney, and “there’s something called attorney-client privilege.”

Giuliani also mentioned the privilege in an interview with the New York Times, although he didn’t say whether he would refuse to comply with the subpoena. “We’re getting really close to, if we haven’t met, the standard of the McCarthy hearings where nobody seems to care about things like attorney-client privilege,” he said.

John Bies, a former lawyer in the Obama administration’s Department of Justice, wrote in a Sept. 30 post for the Lawfare blog that Giuliani might have to rethink any plans to rely on attorney-client privilege. According to Bies, it’s unclear whether much of the information of interest to Congress is even protected by the privilege.

“The privilege exists to protect the confidential communication between a client and an attorney made for the purpose of obtaining legal advice,” said Bies, who is currently the chief counsel at American Oversight, a government accountability nonprofit. “It does not protect, for instance, communications your attorney may have had with, say, foreign government officials—or, for that matter, with U.S. government officials.”

Pushing arguments about potential corruption to foreign officials doesn’t appear to involve providing confidential legal advice, Bies said. “It is not even clear that Giuliani’s conduct constitutes legal work performed in his capacity as Trump’s attorney, even if it were charitably viewed as something other than political campaign work,” Bies said.

Nor does it appear that Trump was conveying confidences to Giuliani, rather than directing him to undertake nonlegal activities on his behalf, Bies wrote.

Even if some of the communications are privileged, they would have little protection against compelled congressional testimony, Bies asserted. He cited three reasons why.

• First, Congress has long taken the position that it can insist on disclosure of privileged communications.

• Second, attorney-client privilege can be waived when privileged communications are disclosed to a third party—and Giuliani has discussed his efforts with a large number of people.

• Third, the crime-fraud exception to attorney-client privilege could apply if the actions violate campaign finance laws.

Bies also considers whether executive privilege would be available to Giuliani. Bies concluded that the answer is no because Giuliani is representing Trump in a personal capacity, rather than an official capacity.

“Representing the president in his personal capacity involves a different set of interests and concerns than the official, governmental decision-making processes executive privilege is designed to protect,” Bies said.

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.