Black man convicted by all-white jury in room with Confederate flags gets new trial, appeals court says

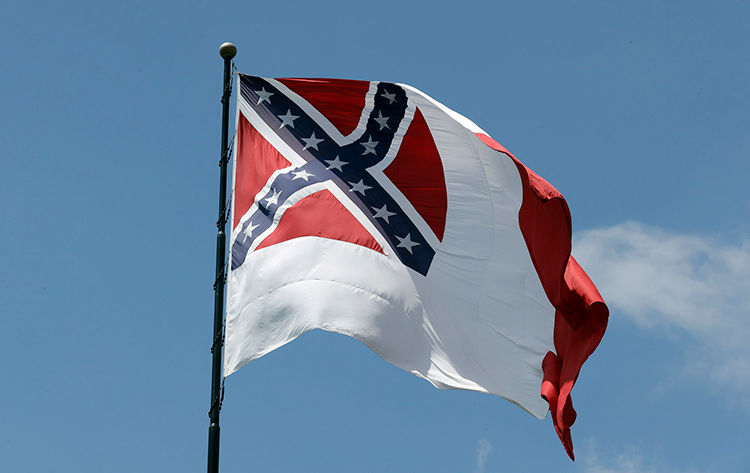

A Confederate flag known as the “Blood Stained Banner” was one of the pieces of memorabilia in the jury room of the Giles County courthouse. (AP Photo/Chris O’Meara, File)

The Tennessee Court of Criminal Appeals has ruled a Black criminal defendant is entitled to a new trial because the all-white jury that convicted him deliberated in a room "adorned with various mementos of the Confederacy."

The intermediate appeals court cited two separate reasons for reversing the aggravated assault conviction of Tim Gilbert. One was because the Confederate memorabilia amounted to prejudicial extraneous information. The second was because a trial judge had improperly admitted a prosecution witness’s inconsistent statement to police to support the government’s case.

The New York Times, the Washington Post and the Tennessean covered the Dec. 3 opinion.

A door to the jury room in Giles County is inscribed “UDC Room,” a reference to the United Daughters of the Confederacy, a group of descendants of Confederate soldiers dedicated to promoting their memory. (The UDC says on its website, however, that it denounces groups that promote racial divisiveness or white supremacy).

A glass panel on the jury-room door has the UDC insignia, which includes the “Stars and Bars” flag—the first national flag used by the Confederate States of America.

Another version of the Confederate flag known as the “Blood Stained Banner” is in a large frame on the wall of the jury room. A plaque on the flag frame reads, “Confederate Flag Property of Giles County Chapter #257 UDC.”

Also hanging on the wall are framed portraits of Jefferson Davis, the president of the Confederacy, and Confederate general John C. Brown.

The appeals court said the memorabilia, particularly the Confederate flag, violated Gilbert’s right to trial by an impartial jury.

“Although the UDC is a private organization and although the flag belongs to that organization, the location of the flag and the other items within the courthouse in a room used on a regular basis, which location has not been historically viewed as a public forum, clothes all of the items, including the flag in particular, with the imprimatur of state approval,” the appeals court said.

“The specter of racial prejudice that might be ascribed to the flag in the UDC room is particularly troublesome given that ‘the jury is to be a criminal defendant’s fundamental protection of life and liberty against race or color prejudice.’ “

The extraneous information raised a presumption of prejudice and shifted the burden to the state to show the information was harmless, the appeals court said.

The state had cited the fact that the same defendant was acquitted by jurors using the same room in an unrelated case. The appeals court said that was not sufficient to rebut the presumption of prejudice.

The New York Times spoke with Michael Working, who led the Tennessee Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers when the group filed a brief supporting Gilbert.

He pointed out that the ruling put the burden on the prosecution to prove the jury room was free of coercion and influence, rather than requiring the defendant to show prejudice.

“That’s a big step,” he told the Times.

Working also wondered whether the ruling could have implications for Confederate statues outside courthouses.

See also:

ABA Journal: “Judicial portraits and Confederate monuments stir debate on bias in the justice system”