Trans-Pacific Partnership raises question: How should governments and corporations resolve disputes?

Photo Illustration by Brenan Sharp/Shutterstock

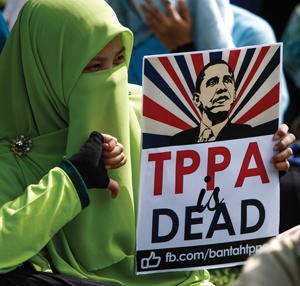

The Trans-Pacific Partnership appears to be a long way from going into force, but as a political issue, it clearly has arrived.

There is little dispute over the potential impact of the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The massive multilateral agreement, which took 10 years to negotiate, would create a framework of new trade rules for the United States and 11 other countries bordering the Pacific Ocean: Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam, which together account for nearly 40 percent of the world’s economy. Notably absent from the list of participating countries is China, which the United States deliberately excluded from the creation of the agreement in order to establish trade rules conforming to U.S. ideas. The United States has indicated a willingness to allow China to join the TPP later, after the agreement’s rules have been put into place. China, however, has not shown a significant interest in joining the TPP, partly because the country could not satisfy a variety of TPP standards. For instance, China’s online censorship would conflict with the TPP’s standards on electronic commerce.

Signed by trade ministers on Feb. 4, the TPP will go into effect after it is ratified by at least six countries that account for 85 percent of the combined gross domestic production of the 12 TPP nations. To reach that threshold, both the United States and Japan must ratify the treaty.

But signing the TPP was the easy part, since it was the trade ministers of the member countries who negotiated it. Ratification promises to be more problematic, since it requires legislative approval. The treaty faces strong opposition in many signatory countries, including Australia, Canada, Chile, Japan, New Zealand and the United States.

In the United States, it is something of a surprise that the TPP, which was negotiated in relative obscurity, has become a hot-button issue in the presidential election. President Barack Obama is the TPP’s primary champion, and in June 2015, he scored a political victory—with the support of Republicans in Congress over opposition from members of his own Democratic Party—when he was authorized to negotiate trade deals that cannot be amended or filibustered by Congress.

The GOP, which historically has favored free trade agreements, has shown little support for the TPP. Last year, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Kentucky, told the Washington Post that if the administration proceeded with its plan to send the treaty for confirmation to Capitol Hill by this summer, the Senate would reject it. “It would be a big mistake to send it up before the election,” he said. “There’s significant pushback all over the place.” There is similar opposition to the TPP in the House.

The presidential nominees of the two major parties both have expressed opposition to the TPP. Republican nominee Donald J. Trump has called the TPP “a horrible deal.” Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton’s position on the treaty is a bit more complicated. Although she supported the TPP as Obama’s secretary of state, she now opposes it. In May, the Post quoted Clinton as saying, “I oppose the TPP agreement—and that means before and after the election.”

Photographs by Kyodo via AP Images

There is widespread opposition to the TPP outside of Congress and the campaign trail as well. Labor unions, environmental groups, internet freedom groups and consumer rights organizations warn that the agreement would enable corporations to export more manufacturing jobs to low-wage nations, limit competition and increase prices for pharmaceuticals and other high-value products by expanding U.S. standards for patent protections to other countries.

But that opposition doesn’t necessarily mean the TPP is doomed. Many establishment politicians, especially in the GOP, support the deal. So, too, do many large and powerful corporations, including Apple, Citigroup, Disney, ExxonMobil, Halliburton, Microsoft and Goldman Sachs, which many opponents interpret as proof that it must be bad for workers.

“It is definitely too soon to tell whether TPP will be ratified,” says Timothy C. Brightbill, a partner in the Washington, D.C., office of Wiley Rein and an ABA representative on the Industry Trade Advisory Committee in the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. “Trade agreements are always close votes in Congress. I would expect it would be a challenging process for the TPP to gain final approval.”

Meanwhile, negotiations on a similar trade agreement that would span the Atlantic Ocean are proceeding under the radar, at least on this side of the pond. The Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership would establish new trade rules for the United States and members of the European Union, where it has triggered widespread protests.

Once the TTIP is finalized, ratification could be even more difficult than for the TPP, since the TTIP must be ratified by every member state in the EU, and that kind of unanimous support is far from a given. French Prime Minister Manuel Valls said in a speech to members of his political party, “I can tell you frankly, there cannot be a transatlantic treaty agreement. This agreement is not on track.”

READY TO RUMBLE

Both advocates and opponents of the TPP come to the debate with plenty of support for their positions.

Advocates maintain that the agreement will bring big economic benefits. The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, which handled negotiations for the administration, maintains that the TPP will reduce or eliminate tariff and nontariff barriers across substantially all trade in goods and services. As a result, the gross domestic product of participating countries could rise by an average of 1.1 percent by 2030, according to the World Bank. The economic benefit for the United States, admittedly, would be below this average. The U.S. GDP would rise by just 0.5 percent by 2030, according to a study issued in January by the Peterson Institute for International Economics. Still, that equates to an additional $131 billion for the U.S. economy, supporters note.

Moreover, say supporters, the agreement offers important geopolitical benefits for the United States. “The TPP means that America will write the rules of the road in the 21st century,” Obama said in a statement posted online. “If America doesn’t write those rules— then countries like China will. And that would only threaten American jobs and workers and undermine American leadership around the world.”

Critics counter that the TPP will hurt, not help, the United States. The treaty would lower U.S. GDP by 0.54 percent after 10 years and cost the United States an estimated 448,000 jobs, according to a study issued in January by Tufts University.

Photo Illustration by Brenan Sharp/Shutterstock

Moreover, the TPP will worsen income inequality in the United States, says David Rosnick, an economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C. He found that the TPP would boost incomes for the highest-earning 10 percent of the population, while decreasing income for all other workers above the poverty line. The Tufts University study concurred that the TPP would exacerbate income inequality. Competitive pressures on labor incomes, combined with employment losses, would “push labor shares of national income further down, redistributing income from labor to capital in all countries” that are parties to the TPP, the study states.

Public Citizen, the consumer rights advocacy organization created by Ralph Nader, warns that the TPP will allow unsafe food to be imported into the United States, boost medical costs by giving pharmaceutical companies new rights to keep lower-cost generic drugs off the market and undermine reforms affecting large banks and other financial institutions.

A POTENTIAL POWDER KEG

And then there is the TPP’s Article 9, which addresses what the agreement describes as investor-state dispute settlement. That chapter has become the focus of strident opposition from many who claim that ISDS dangerously undermines the ability of governments to set public policy.

ISDS “severely constrains environmental, health and safety regulation, and even financial regulations with significant macroeconomic impacts,” wrote Joseph E. Stiglitz in a Jan. 10 op-ed in The Guardian, a British newspaper that publishes a U.S. edition. As a result, the TPP “may turn out to be the worst trade agreement in decades.” Stiglitz is a Nobel Prize-winning economist who teaches at Columbia University in New York City.

At first, ISDS might seem to be one of the more innocuous provisions in the TPP. It enables a company operating in a foreign country to seek redress from that country when its business interests are expropriated or otherwise unfairly harmed by that country’s authorities. The aggrieved company may bring a claim for arbitration, instead of having to risk bias by litigating in a foreign country’s courts.

The arbitration would be conducted by a three-member panel that operates outside the supervision of any national court system. Unless the national parties decide otherwise, the complaining party would pick one private arbitrator, the accused nation would pick another arbitrator, and those two arbitrators would select the third member of the panel. The process would follow the rules of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes or the U.N. Commission on International Trade Law. If the panel were to find that the accused country acted wrongfully, the country would have to compensate the company for the economic harm it suffered. Awards would be enforceable in the courts of every signatory of the TPP.

Protesters in New Zealand. Photograph by Sipa via AP Images.

In addition, a winning complainant could seek to enforce the award in the courts of other countries that signed the ICSID Convention, the New York Convention or the Inter-American Convention. That would allow enforcement in almost every country on the planet.

Investor-state dispute settlement isn’t some radical new legal innovation. It has been included in many international trade agreements over the past 50 years, says Robert E. Lutz II, a professor at Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles and a past chair of the ABA Section of International Law.

ISDS applies only against countries that accept it, as part of an international trade agreement, such as the TPP or the North American Free Trade Agreement. And ISDS doesn’t protect against all foreign government misbehavior. It provides compensation when a signatory country:

- Treats a foreign investor or company less favorably than domestic investors or companies.

- Fails to treat a foreign investor or company “in accordance with applicable customary international law principles, including fair and equitable treatment.”

- Expropriates a foreign investment or company without due process of law and payment of adequate compensation.

Over time, however, lawyers have prodded arbitrators to interpret these ISDS clauses in a surprisingly expansive way. As a result, settlement arbitrators have repeatedly ordered governments to pay millions of dollars when foreign companies’ anticipated profits were hurt by health, safety, environmental or labor protections.

Protesters in Malaysia. Martin Hunter/SNPA via AP.

In Metalclad v. Mexico, ISDS arbitrators ruled that Mexico indirectly expropriated the assets of a U.S. waste management firm and denied the firm “fair and equitable treatment” because the firm was denied a permit to expand a toxic waste facility onto an environmentally sensitive area. Mexico was ordered to pay $16.7 million to compensate the U.S. firm. In Abengoa v. Mexico, ISDS arbitrators found expropriation and unfair treatment when a Spanish firm was refused a license to operate a toxic waste disposal plant on a fault line near an environmental preserve. Mexico was ordered to pay over $40 million.

Similar cases are ongoing. Costa Rica is fighting an ISDS proceeding over its rules protecting endangered sea turtles. Peru is battling over its rules to stop lead pollution. Germany is fighting such proceedings brought by Swedish energy firm Vattenfall AB, which is challenging Germany’s decision to phase out nuclear power.

“In contrast to court opinions, arbitration submissions and awards are often confidential,” states the website of the law library at Columbia University. “This makes locating the awards much more difficult than locating court opinions. ... These awards are sometimes excerpts (and confidential information has been removed).” The Columbia site lists publications and websites that publish arbitration decisions.

CAUTIOUS GOVERNMENTS

The mere threat of an adverse ISDS ruling has caused countries to back away from actions to protect health, safety, workers’ rights and the environment. Here is one example: After Canada banned a toxic gasoline additive called methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl, it was forced into an ISDS proceeding by Ethyl Corp., which had been selling the additive in Canada. Ethyl argued that Canada’s ban diminished its anticipated profits and demanded that Canada pay the company all that it would have earned from selling MMT in Canada. The settlement panel handed down a preliminary ruling in favor of Ethyl. Before the arbitrators could issue a final decision, Canada settled. The nation repealed its ban on the additive, paid the firm $13 million in damages and legal fees, and posted ads saying that MMT was safe—even though Ethyl’s home country, the United States, bans its use in gasoline.

Some experts point to all this and conclude that investor-state dispute settlement is a pernicious impediment to public policy. “ISDS is a major problem that is undermining the rights of governments to regulate in the public interest,” says Lori M. Wallach, director of Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch.

The Obama administration asserts that the TPP contains a new, improved ISDS chapter, which avoids past problems. The administration points, for instance, to Article 9.16, which states, “Nothing in this chapter shall be construed to prevent a party from adopting, maintaining or enforcing any measure otherwise consistent with this chapter that it considers appropriate to ensure that investment activity in its territory is undertaken in a manner sensitive to environmental, health or other regulatory objectives.”

Protesters in Philippines. Photograph by AP Photo/Bullit Marquez.

Lutz says, “Arguably, this completely prevents ISDS challenges to ‘environmental, health or other regulatory objectives.’ ” He notes that a similar provision in NAFTA protected the United States when an investor-state dispute settlement challenge was brought against California’s ban on the gasoline additive MTBE. The state had banned the additive in order to protect the environment and public health, and this ban did not unfairly harm a foreign company selling chemicals used to make the additive, an ISDS arbitral panel held in Methanex Corp. v. United States.

ArTIcle Scrutiny

The NAFTA provision at issue in that dispute, Article 1114, Paragraph 1, has the same language as the TPP’s Article 9.16, except that the NAFTA provision protects only environmental regulations, while the TPP provision protects “environmental, health or other regulatory objectives.”

Brightbill also thinks highly of Article 9.16. “It is too soon to tell if this creates a complete firewall,” he says. “But the Obama administration has heard the concerns of TPP opponents and has tried in the text to respond to those complaints. Hopefully, this will create a better balance of the right to regulate and right to protect investments.”

Others doubt the effectiveness of Article 9.16. They note that the Methanex interpretation of Article 9.16’s language is at odds with the rulings in Metalclad and Abengoa. That’s not a problem for ISDS arbitrators, says Wallach, since they are not bound by precedent. Rather, the inconsistency is a problem for nations threatened with ISDS proceedings because they can’t know whether arbitrators will apply Article 9.16 in accordance with Methanex or Abengoa.

Moreover, skeptics add, there is a large loophole in the TPP’s Article 9.16: It protects only those regulations that are “otherwise consistent with this chapter.” So the article protects only those government actions that do not create ISDS liability—and thus do not need protection under Article 9.16. This provision is simply “irrelevant,” Wallach says.

Article 9.16 is further undermined by another provision in the TPP. Article 25.5, Paragraph 2 states that before taking regulatory action, signatory nations should “assess the need” for such action and “examine feasible alternatives.” ISDS arbitrators have used this language in other trade agreements to attack government regulations, and the same can be done under the TPP. “This gives the arbitral panel plenty of discretion to decide if the measure being challenged is strictly necessary or whether there were less intrusive measures that could be taken,” says Timothy A. Canova, a professor at Shepard Broad College of Law at Nova Southeastern University. Rather than providing any real protection, Article 9.16 is simply a “fig leaf,” Canova says.

Protesters at the Democratic National Convention. AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite

The TPP’s Annex 9-B imposes another limit on investor-state dispute settlement. It declares that nondiscriminatory government regulations that “protect legitimate public welfare objectives, such as public health, safety and the environment, do not constitute indirect expropriations, except in rare circumstances.” Annex 9-B can thus protect public welfare regulations against ISDS claims of indirect expropriation. Suppose that tougher environmental standards prevent a foreign company from operating a toxic waste dump in some wetlands. These regulations would not directly expropriate the company’s toxic waste dump, but because they would prevent the dump from operating, the standards could constitute indirect expropriation. The foreign company might thus win an indirect expropriation claim under ISDS—were it not for Annex 9-B.

But Annex 9-B’s protections are limited. It is a defense only against claims of indirect expropriation. It does not protect against other common ISDS claims, such as discriminatory treatment or violation of customary international law principles. And these two sorts of claims have been the basis of repeated ISDS rulings against government efforts to protect the environment and public welfare.

Moreover, even the protection against indirect expropriation claims is qualified. Annex 9-B states that nondiscriminatory public welfare regulations “do not constitute indirect expropriations, except in rare circumstances.”

That creates a big loophole, Canova says. “The TPP doesn’t define ‘rare circumstances.’ That gives a lot of discretion to the arbitrators.”

Canova has little faith that ISDS arbitrators will use their discretion fairly. That’s because the pool of potential arbitrators is largely composed of attorneys who bring ISDS claims. “When you look at who composes the arbitral panels, they are essentially lawyers who represent large corporations and investors in these types of suits,” Canova says.

Robert Lutz II. Scott J. Ferrell/Congressional Quarterly/Getty Images.

One example is Railroad Development Corp. v. Guatemala. In that case, an ISDS arbitral panel considered whether Guatemala had violated customary international law principles when it initiated a process to revoke RDC’s contract to provide railway services.

The United States, El Salvador and Honduras filed submissions supporting Guatemala and urging a narrow interpretation of “customary international law principles.” These three nations, as well as Guatemala, asserted that customary international law principles arise only from agreements and decisions made by nations, not by interpretations made by arbitral panels. These countries also pointed to Annex 10-B of the Central American Free Trade Agreement, under which the ISDS proceeding was brought. The annex stated, in part, “The parties confirm their shared understanding that ‘customary international law’ ... results from a general and consistent practice of states that they follow from a sense of legal obligation.”

However, this treaty language and the representations by four of the treaty signatories did not hinder the arbitral panel. The panel conceded that ISDS arbitral rulings “do not constitute state practice,” but held such rulings are evidence of what state practice is. Then the panel adopted the broad interpretation of “customary international law principles” set out in a prior ISDS arbitration ruling, declaring that prior ruling “persuasively integrates the accumulated analysis of prior [arbitral] tribunals.” Applying the broad interpretation made by other arbitrators—not nations or their courts—the panel found Guatemala guilty of violating customary international law principles.

NO SMOKING

The TPP contains one exceptional new ISDS provision. Even critics agree this provision has no loopholes and will effectively halt ISDS claims against some public welfare regulations. The catch, however, is that the provision grants protection only to government efforts to control tobacco use.

Lori Wallach. Photograph by Earnie Grafton.

Article 29, Paragraph 5 of the TPP states that a nation “may elect to deny” foreigners the right to bring ISDS “claims challenging a tobacco control measure.” If a nation makes this election, “such a claim shall not be submitted to arbitration” under ISDS. If a nation has not made this an election before the commencement of an ISDS claim against a tobacco control measure, the country may make the election “during the proceedings.” Finally, if a nation elects to deny ISDS claims against its tobacco control measure, “any such claim shall be dismissed.”

A footnote states that “tobacco control measure” is to be interpreted broadly. “A ‘tobacco control measure’ means a measure related to the production or consumption of manufactured tobacco products (including products made or derived from tobacco), their distribution, labeling, packaging, advertising, marketing, promotion, sale, purchase or use, as well as enforcement measures, such as inspection, recordkeeping and reporting requirements.”

Critics of investor-state dispute settlement laud this provision as a powerful protection for government anti-smoking regulations. However, the strength of this provision provides a vivid contrast with the TPP’s other limits on ISDS. Why does the TPP not include similarly strong limits on settlement claims against other public welfare regulations?

Experts suggest that there is a policy reason for treating anti-tobacco regulations differently than other public health regulations. “Unlike alcohol or other types of drugs, any exposure can be dangerous,” Lutz says.

And there is a global commitment to curtail tobacco use. The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control has been signed by 180 countries (out of 196 U.N. member states), including all 12 nations that have signed the TPP. The framework convention requires all signatory countries to prevent and reduce tobacco use.

“One part of that treaty said that countries should not provide any incentives for the tobacco industry, and many would consider ISDS an incentive. So the carve-out is consistent with that. It provides for the ability of countries to regulate for the health and welfare of their citizens,” Lutz says.

Health and safety issues

TPP critics, however, dispute the rationale for treating tobacco control regulations differently than other public health or safety regulations. Tobacco is important, but it is no more important than many other public health issues, such as toxic waste or air pollution, they say. Yet the partnership provides no ISDS carve-out for these or other public health issues.

Supporters counter that exempting all health and safety regulations from ISDS would go too far. “Any regulation on behalf of the health and safety of citizens can be a cloaked protectionist action,” Lutz cautions.

So why did the authors of the TPP create a carve-out for one type of health regulation? The answer, suggest many experts, is politics. Philip Morris’ ISDS challenges to Australia’s and Uruguay’s cigarette packaging laws created a great deal of bad publicity for ISDS. The tobacco company’s actions “focused attention on ISDS,” and many people believed this “was an example of how ISDS could be misused to undermine important public health goals,” Brightbill says.\0x2029

Timothy Brightbill. Photograph by David Hills Photography.

This had to be addressed if the TPP were to be ratified in the United States and other signatory nations. So the TPP negotiators added the exemption for tobacco control measures. “By mid-2015, adding a tobacco carve-out became a political imperative so the Obama administration could claim that the TPP’s ISDS regime was somehow fixed,” Wallach says.

The carve-out undermined ISDS but only to a very limited extent. “It was felt that for tobacco products, the danger of limiting public health regulations outweighed the danger of taking away legal recourse for these companies,” Brightbill says.

The Obama administration says there is no need to worry about any harmful ISDS arbitral rulings because all ISDS awards are subject to subsequent review, either by domestic courts or international review panels. This is true, but the reviews are extremely limited.

There is no substantive review of awards. Even clear errors of law or fact are not grounds for overturning an award. “There is no review of the merits of the case, the facts of the case or the arbitrators’ interpretation of ISDS standards,” Wallach says.

“ISDS awards can be reversed only for gross procedural error,” Canova says. And only certain types of gross procedural errors can result in reversal: The arbitral panel was not properly constituted; the panel manifestly exceeded its powers; an arbitrator was corrupt; the panel committed a serious departure from a fundamental rule of procedure; or the panel failed to state the reasons for its award.

Awards may be revised if new facts are discovered. “There is rarely an annulment or a modification in the amount of the award,” Wallach says.

Even if a nation does manage to get an ISDS award annulled, that does not necessarily end the matter. The foreign company that brought the arbitration may simply bring the dispute before another ISDS panel.

It is unclear how great a role investor-state dispute settlement will play in the upcoming ratification debate over the TPP. Yet for many, ISDS is reason enough to oppose the TPP. ISDS “is part of a corporate agenda to dilute government regulation,” Canova says. “It is an attempt to rebalance, in a fundamental and dangerous way, the power of the state and investors and corporations. For me, it is a deal killer for the TPP. ISDS is a deal breaker.”

Steven Seidenberg is an attorney and freelance reporter in the greater New York City area.

This article originally appeared in the November 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: "Turmoil in the Pacific: A controversial trade agreement raises questions about how disputes should be resolved between governments and private corporations."