Features

The lawyer who took down Lance Armstrong is on a mission to end the culture of cheating

Photo of Travis Tygart by Michael Friberg

On the wall, he noticed a poster of Lance Armstrong on his bike with a quote: "What am I on? I'm on my bike, busting my ass six hours a day. What are you on?"

Tygart appreciated Armstrong's message about hard work and the encouragement the cyclist had given millions of cancer victims.

"Lance was a true hero to so many people," Tygart says. "He had beaten cancer, won seven times at the Tour de France, dated Sheryl Crow and had become an American icon. His story was such an inspirational story to so many people, including me."

Little did Tygart know at the time how intertwined his life would become with Armstrong's. During the past decade, the two men have battled mightily.

They accused each other of lying and cheating. They threatened each other's financial future. Diehard advocates of Armstrong's innocence threatened Tygart.

Today, everyone knows Lance Armstrong doped in order to win.

Travis Tygart is the reason they know it.

Tygart has become America's evangelist of ethics. His sermons advocate playing by the rules and proclaim the pitfalls of cheating. He preaches around the country like Billy Graham and Billy Sunday. His congregations are bar associations, law firm retreats, investment banking seminars, law school lectures, general counsel conferences and corporate compliance events.

"Cheating is cheating, whether you are practicing law or selling mortgage-backed securities," Tygart says. "We have lost our way in this country. It started with sports and trying to give kids and young adults a little bit of an advantage, and it ends with hedge fund managers going to prison for insider trading."

Tygart's sermons are packed with personal anecdotes, accompanied by a PowerPoint that flashes photographs of Floyd Landis, Marion Jones, Kelli White and Barry Bonds.

Tygart has been near or at the heart of nearly every major doping investigation during the past decade.

He played a key role in the 2002 investigations into BALCO, the Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative. The San Francisco business is alleged to have provided performance-enhancing drugs to sprinters Jones and Tim Montgomery and to baseball players Bonds and Jason Giambi.

Five years later, Tygart was instrumental in Operation Raw Deal, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration's probe into 30 Chinese companies that shipped 11.4 million doses of illegal growth hormone substances to 56 laboratories in the U.S.

He has advised Major League Baseball and the National Football League in the development of their anti-doping policies. His best friend describes Tygart as the "Eliot Ness of sports."

"It has become culturally acceptable to cheat," Tygart says. "We have become a society that accepts a win-at-all-cost attitude—as long as you don't get caught."

But none of those other doping targets, including Bonds, came close to the global popularity and celebrity of Armstrong. And none of those investigations were anywhere near as controversial as USADA's probe into cycling.

"Lance—and just about everyone around Lance—believed that he was too big to fail," Tygart says. "We live in a society that feels that if you get too big and too popular, you will never be held accountable. That goes right to the heart of the rule of law."

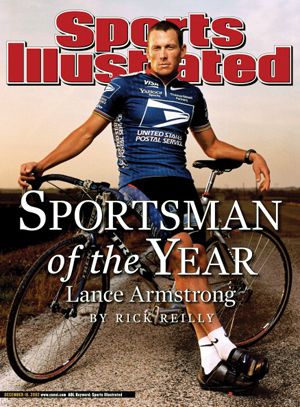

Lance Armstrong on the cover of Sports Illustrated, 2002. Photo by Jonas Karlsson/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images.

NOSE TO NOSE

Tygart is 43—the same age as Armstrong. Both men played sports. But there, the similarities end.

"Travis and Lance are complete opposites, except that both wanted to win," says New York Times sports reporter Juliet Macur, who covered the Armstrong scandal for more than a decade. "Lance is a symbol of all that is wrong in sports and in our society, while Travis followed all the rules—and that drove Lance crazy.

"Lance is an atheist, while Travis is a faithful, churchgoing Christian," says Macur, author of the book Cycle of Lies: The Fall of Lance Armstrong. "Travis' family is very tight-knit and supportive, while Lance is scarred by alcoholism and divorce."

Tygart's great-grandparents migrated to the U.S. from Lebanon. His father and grandfather were lawyers. So were his uncles. They raised Tygart in the Christian faith with strict biblical principles. No lying. No cheating. No stealing. Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

In high school, Tygart played baseball and basketball. Even as a teenager, Tygart displayed leadership skills. When as class president he was asked to lead the graduating class in prayer, a school official reviewed his written prayer and instructed Tygart to remove references to Jesus. Tygart refused, saying he wouldn't offer a prayer that didn't reflect his beliefs.

"Travis has always displayed a steely underbelly," says Craig Camp, who has been Tygart's best friend since they were in kindergarten together. "He's a natural leader and has an unshakable character."

Camp says that Tygart, when he was president of his fraternity at the University of North Carolina, caught a very popular fraternity brother eating from the Pi Kappa Alpha kitchen. The schoolmate had not paid his fraternity bill. Tygart kicked him out.

"Why not just look the other way?" Camp said others asked his best friend.

"That would have been the easy way out," Tygart responded. "What would I say to the other fraternity brothers who had paid their dues?"

"Travis took a lot of flak for that decision, but he knows right from wrong and he's always been willing to stand up for right, even when it cost him," says Camp, who is a director at Merrill Lynch in Atlanta.

Despite a family filled with lawyers, Tygart graduated from UNC with a degree in philosophy, and he taught high school economics and world history for three years.

"I fought hard against going to law school, even though I kind of knew that was my destiny," Tygart says. "I finally gave in, and it has proven to be one of the wisest decisions of my life. Law school taught me so many skills and tools that I used throughout this process, including critical thinking and how to prepare a complex case for public presentation."

He graduated fom Southern Methodist University's Dedman School of Law in 1999 and went to work as a litigator at Fulbright & Jaworski in Dallas.

But Tygart's passion was sports, and he read everything he could about sports law. In 2000 he joined Denver-based Holme Roberts & Owen (which has since merged into Bryan Cave) because of the firm's sports law practice. His clients included the U.S. Olympic Committee and the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency.

Two years later, Tygart became USADA's legal director.

Travis Tygart in Paris last year on the way to an anti-doping inquiry by the French government. AP Photo/Francois Mori

THE ANTI-DOPING CRUSADE

USADA was founded in 2000 as a 501(c)3 after the leaders of the U.S. Olympic Committee decided it was best to assign anti-doping efforts to an independent body.

USADA was created by Congress and gets $9 million of its $14 million annual budget from the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy, but the agency gets none of its oversight authority or power from the federal government. Instead, the Colorado Springs-based organization's authority is completely contractual.

Athletes who compete in marathons, swim meets, amateur hockey and soccer events, and a host of other Olympic-related events are required to sign a licensing contract to be a USADA member. As such, the athletes agree to abide by the agency's rules, which include no cheating and no use of performance-enhancing drugs.

More than 15 million people participate in the Olympic-related events—from local races, swimming contests and soccer matches to the Pan American and Paralympic games and, of course, the Olympics. All of them fall under USADA's jurisdiction.

"I have seen an 8-year-old at a noncompetitive swim meet being given Monster and 5-Hour Energy," Tygart says. "I saw the parents of a 14-year-old inject high dosages of testosterone into their child to help make the kid better at rollerblading.

"This idea that we need to take something to think faster, to stay up longer and to give us an advantage is ingrained in our society," he says.

"There is this mentality that we will do what it takes to be the best and not worry about the consequences until later. It starts with youth sports and follows the rest of our lives," he says.

Then there's the elite of the elite—3,000 athletes who are competing at the Olympic level. USADA requires these athletes to let the agency know their whereabouts at all times so officials can administer unannounced drug tests.

About a month after Tygart started his job at USADA, Armstrong called him to complain about this rule. "This is bullshit," Armstrong yelled, according to Tygart. "Showing up at my house to do a drug test is not right and it's not fair."

Tygart says he told Armstrong that the surprise tests are the best way to catch cheaters.

"If you're clean, as the poster says, you have nothing to worry about," Tygart said.

Tygart said he wanted nothing more than to believe that Armstrong was clean.

"People need heroes and Lance was a hero to so many people, including many people I know personally," Tygart says. "I prayed that the rumors that he had doped were untrue."

In 2006, Tygart received a surprise call from a close adviser to Armstrong saying the cyclist wished to donate $250,000 to USADA's anti-doping efforts.

Tygart politely turned down the gift, saying it would be inappropriate for the agency to receive money from an athlete it might have to drug-test in the future. But the call raised Tygart's suspicions about the motivation behind the offer.

In the spring of 2010, Tygart, who had been promoted to CEO of USADA three years earlier, received a phone call from Landis, a former teammate of Armstrong's on the U.S. Postal Service team. That call set in motion everything that has happened since.

Landis won the 2006 Tour de France, but he was stripped of the title the following year when he was charged with using performance-enhancing drugs.

In a conference room at the Marriott Hotel in Marina del Rey, California, Tygart says, Landis told him a story that was stunning in its detail. According to Tygart, Landis described the scene when members of the USPS team, including Armstrong, were on the team bus headed toward the hotel near the next stage of the 2004 Tour. The bus driver suddenly pulled over to the side of the deserted road.

In minutes, according to Landis' story, the bus was transformed into a medical facility. Team doctors traveling on the bus quickly injected the cyclists, including Armstrong, with chilled blood from transfusion bags. That blood, taken from the cyclists before the race, increased their red blood cell count, which had been depleted from the rigors of the race. The replenished blood cells acted like a super energy shot into their bodies, according to Tygart.

"The cycling team had created the cone of silence," he says. "Those participating agreed to take the cheating to their graves, and they were sophisticated and financially backed enough to beat the testing in place."

But Landis' testimony was the key. Soon, Tygart had other cyclists confessing.

Tygart and his team developed a strategy for the investigation. Over the next few months, 10 cyclists confessed and provided insider details that implicated Armstrong, team doctors, trainers and other officials involved in professional cycling.

Floyd Landis testifies at a 2007 arbitration hearing. Photo by Reuters/Max Morse.

THINGS GET OFFICIAL

About that same time, Tygart learned that U.S. Attorney Andre Birotte Jr. of the Central District of California, who had handled the BALCO inquiry, had opened an official criminal investigation into Armstrong and others in cycling.

Tygart cooperated fully, giving criminal investigators all the evidence he had obtained. He also agreed to put USADA's investigation on the back burner while the feds took the lead.

After a nearly 18-month probe, Birotte's office recommended seeking an indictment against Armstrong, according to multiple media reports. They predicted a 99 percent probability of success at trial.

But in February 2012, Birotte shocked everyone when he announced he was ending the investigation without bringing any charges against Armstrong. He offered no explanation.

Tygart was stunned. Within hours, he posted an announcement on USADA's website.

"Unlike the U.S. attorney, USADA's job is to protect clean sport rather than enforce specific criminal laws. Our investigation into doping in the sport of cycling is continuing, and we look forward to obtaining the information developed during the federal investigation."

Only a few days later, the USADA board voted to officially move forward with its investigation.

"We decided if we were going to follow our oath to protect clean athletes, then we had to move forward with this matter," says Tygart. "If not, then we might as well shut down as an anti-doping agency."

On June 4, 2012, Tygart sent a letter to Armstrong's lead lawyer, Tim Herman of Austin, Texas, asking that Armstrong come clean and tell everything he knew about doping in cycling.

Washington, D.C., lawyer Robert Luskin, also representing Armstrong, responded.

"We will not be a party to this charade," Luskin wrote. "Lance has publicly and repeatedly made clear that he never doped.

"But neither will we be spectators to a lynching," Luskin continued. "This investigation is a disgrace. Far from cleaning up cycling or discouraging the use of performance-enhancing drugs, your conduct will undermine USADA's legitimacy and sabotage its mission."

Luskin also stated that if USADA continued to "vilify Lance Armstrong," the legal team would take action to "expose your motives and your methods and to hold you accountable for your conduct."

Luskin declined to discuss Tygart or the case with the ABA Journal. Herman did not respond to inquiries.

The letter did not persuade or slow Tygart.

On June 28, the USADA board voted to officially charge Armstrong, his team doctor, a trainer, a team leader and others involved in cycling with creating and facilitating a dirty culture for riders. Tygart said USADA would seek a lifetime ban, which would be decided in an arbitration proceeding.

Within days of the USADA charges being announced, death threats from Armstrong's legions of devoted followers flooded Tygart's work and home phones and his personal email.

During his tell-all interview with Oprah Winfrey in January 2013, Armstrong admitted it was "dumb" to tweet an image of himself lounging near his Tour de France jerseys after USADA stripped him of his titles. Photo courtesy of @LanceArmstrong/Twitter.

A LEGAL BRAWL

The Armstrong team responded with a double-barrelled approach: lobbying Congress to eliminate USADA's funding and filing an 80-page suit against the agency and Tygart in federal court in Austin.

The suit, filled with what District Judge Sam Sparks called "totally irrelevant" details, was tossed and refiled. The new complaint argued, among other things, that USADA had gone back too far, exceeding the statute of limitations. But Tygart held firm.

"Our position, and we feel the law clearly supports our position, is that if you lie about doping—which Armstrong did on the record and under oath in an arbitration proceeding—there's the principle of equitable estoppel or fraudulent concealment that tolls the statute of limitations, which allowed us to go back further than the eight years," Tygart says.

On Aug. 20, 2012, a judge rejected Armstrong's arguments, setting the stage for a brawl over the allegations before a panel of arbitrators.

Three days later came a shocking announcement.

"There comes a point in every man's life when he has to say, 'Enough is enough.' For me, that time is now," Armstrong said in a written statement.

The announcement meant he would forfeit the seven Tour de France titles, the Olympic bronze medal he won in 2000 and every other victory he'd achieved since 1998. But despite the white flag, Armstrong remained defiant in opposing Tygart.

"Regardless of what Travis Tygart says, there is zero physical evidence to support his outlandish and heinous claims," Armstrong said. "The only physical evidence here is the hundreds of controls that I have passed with flying colors."

Armstrong accused Tygart of being on an "unconstitutional witch hunt."

The comments only infuriated Tygart, who says Armstrong believed quitting the battle would mean that the evidence against him would never be made public because there would be no arbitration trial.

"Lance would not stop attacking Travis personally for being corrupt," Macur says. "If Lance had just shut up, Travis probably wouldn't have fought back so vigorously."

But respond Tygart did.

On Oct. 10, 2012, USADA posted a 202-page report (PDF) on its website detailing its findings and more than 1,000 pages of supporting documents, including drug tests. The agency cited 26 witnesses, including 11 former teammates of Armstrong's, providing testimony against the cyclist and those around him.

"We knew we could win the legal battle, but we knew we had to win the PR battle because that was about people's minds and public support," Tygart says. "The report had to be substantive, but it also had to be readable. We needed to show people that this was a slam-dunk case."

The reaction was fast and decisive. Nike, Radio Shack, Anheuser-Busch and a half-dozen other corporate sponsors quickly dropped their support of Armstrong. The cyclist resigned from the board of the very foundation he'd created and co-chaired.

For the past year, Tygart has traveled the globe to preach his message of clean living and abiding by the rules.

"There is tremendous pressure today ... to do whatever it takes to win, including cheating," he told SMU law students last fall. "It seems like you have to cheat to win today.

"This is not limited to sports. It is a cultural phenomenon, especially in the U.S., to win at all costs," Tygart said. "Don't get me wrong—there's nothing wrong with winning. We want our athletes and our businesses to be successful. But we have put so much pressure on everyone, from the youth sports level and going all the way up to professional, Olympic and elite levels. It is in banking and Wall Street.

"Whether you are an athlete or running a business or practicing law, if you do it by fraud, it is all going to come down at some point," he said. "Only those who play by the rules are ultimately going to win."

Correction

“Thou Shalt Not Cheat,” October, page 46, should have identified Craig Camp as a director at Merrill Lynch. It also should have reported that Camp was quoting others asking Travis Tygart “Why not just look the other way?” when Tygart kicked a fraternity brother out of the Pi Kappa Alpha kitchen because he hadn’t paid his dues.The ABA Journal regrets the errors.

.jpg)