Lawsuits aim to put iconic folk songs back in the public domain

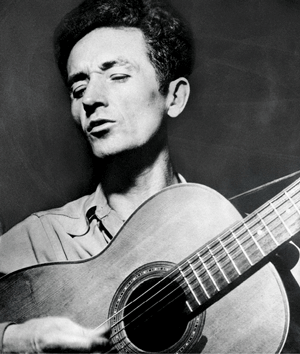

Woody Guthrie. Getty Images

As he hitchhiked around the country in 1940, Woody Guthrie got sick of hearing Irving Berlin’s patriotic hit “God Bless America” on car radios and jukeboxes. So the itinerant folk singer penned his own anthem in response—with lyrics that challenged the concept of private property. He called the song “This Land.” Five years later, Guthrie included the lyrics in a booklet of 10 songs he’d written. He printed copies and put a 25-cent price on the cover—along with “Copyright 1945 W. Guthrie.”

That same decade, striking tobacco workers in Charleston, South Carolina, lifted their voices to an old African-American spiritual, vowing that they’d triumph: “We Will Overcome.” Or did they sing “We Shall Overcome”? At some point, someone tweaked the lyrics, which had been evolving for decades. The word will became shall, and the phrase down in my heart changed to deep in my heart.

Those new words were on the page when Ludlow Music applied for a copyright in 1960, crediting Zilphia Horton, Frank Hamilton and Guy Carawan—not as authors of the original song but as the people who’d written new verses and a new arrangement. The company filed for another copyright in 1963, adding more verses and another name: Pete Seeger. But were these people responsible for the words in the most famous verse? Or do those words belong to the public?

These questions are at the heart of two class action complaints filed this year in federal court in New York. The attorney pursuing both is Mark Rifkin of Wolf Haldenstein Adler Freeman & Herz in New York City. He made headlines in 2015 when he won a lawsuit that ended Warner/Chappell Music’s claim on the copyright for “Happy Birthday to You.” Now, he’s taking on a publisher that administers two of America’s most famous folk songs.

“The work we do in these cases … is serving the public interest,” Rifkin says, emphasizing that artists have to have freedom to create something new based on older works that belong in the public domain. “ ‘This Land’ and ‘We Shall Overcome’ have a common element, which is the way folk music is created in this country. People take work that is already in existence, and they change it—maybe a little, maybe a lot—and they make it their own.”

Paul LiCalsi of Robins Kaplan in New York City represents the defendants in the two suits. He says he’ll be able to prove that his clients—Ludlow Music and its parent company, the Richmond Organization—have valid copyrights. He also argues that “This Land Is Your Land” (as it’s dubbed since a 1956 copyright) and “We Shall Overcome” deserve to be protected from commercial exploitation.

“It’s not so cut-and-dried that this attempt to put this in the public domain is really such a great thing for the culture and for the public,” he says. “If ‘We Shall Overcome’ is in the public domain, what’s to stop a hamburger franchise from saying ‘We shall overcome greasy burgers’?”

LEGAL DISHARMONY

In the litigation regarding Guthrie’s song, Brooklyn rock band Satorii is suing to get back $45.50 it paid for a license to cover “This Land Is Your Land.” The group also wants to release a different version, combining Guthrie’s lyrics with a new melody. According to the lawsuit, Guthrie took his melody from an old hymn that’s known variously as “Fire Song,” “When the World’s on Fire” and “O My Loving Brother.”

The lawsuit argues that Guthrie’s copyright on his lyrics began in 1945, when he printed that booklet. Guthrie died in 1967, and his heirs didn’t renew that copyright when it expired in 1973. But LiCalsi insists that the 1945 songbook doesn’t qualify as a publication.

“We’ve never seen any indication that copies of this thing were sold by Woody to the public,” he says. “At the most, he gave one or two to Alan Lomax, who was his record producer [and] gave one maybe to a manager.”

Rifkin disagrees, saying, “It was obviously offered to the public.”

Folkways Records released a record with Guthrie singing “This Land Is Your Land” in 1951, with the lyrics in the liner notes—but no copyright notice. Finally, Ludlow registered a copyright for the song in 1956, calling it “an unpublished work” and identifying Guthrie as the author of the song’s words and music.

Satorii’s lawsuit argues that this copyright—still administered by Ludlow, with 75 percent of royalties going to Guthrie’s family—is invalid. Woody Guthrie’s daughter Nora Guthrie told the New York Times in July: “Our control of this song has nothing to do with financial gain. It has to do with protecting it from Donald Trump, protecting it from the Ku Klux Klan, protecting it from all the evil forces out there.” (The Woody Guthrie Foundation, where she is president, declined to make her available for an interview.)

In the other suit, a California nonprofit, the We Shall Overcome Foundation, wanted to make a documentary about the civil rights anthem, but Ludlow denied permission to include the song. Another plaintiff, Butler Films, paid $15,000 for a license to use three seconds of “We Shall Overcome” in the 2013 movie The Butler. The producers wanted to feature the song in several prominent scenes, but Ludlow demanded $100,000, a cost the producers say is too much.

Rifkin argues that the 1960 and 1963 copyrights don’t cover the song’s melody or its most famous words. But LiCalsi says the wording change is covered by those copyrights.

“This is a very simple change, but it was obviously a profound change,” he says. “The word will is somewhat passive. It’s an expression of faith that things will change someday.” The song became more assertive with the word shall, he says. “Significantly, it was that version … that caught the imagination of the movement that became popular.”

Rifkin’s lawsuit questions how LiCalsi’s clients can hold a copyright on those words when it isn’t clear who wrote them.

“No one is certain who changed ‘will’ to ‘shall,’ ” wrote Seeger, who died in 2014, in his 1993 book Where Have All the Flowers Gone: A Singalong Memoir.

Adapting lyrics

Dick Weissman, a member of the Journeymen in the 1960s, says it was common practice for folk musicians to claim copyright on old songs they hadn’t written, adding phrases like “adapted and arranged by.” He explains, “The notion is you’re doing some sort of new version of it—which in some cases was quite true and in some cases was a joke. … If we didn’t do this, the record companies would simply keep the money for the publishing and songwriting rights.”

Weissman, author of Which Side Are You On? An Inside History of the Folk Music Revival in America, says this attitude might explain why Seeger and the others put their names on “We Shall Overcome.”

The songwriting royalties from “We Shall Overcome”—about half its annual $70,000 in earnings, LiCalsi says—are donated to a fund for social programs at the Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market, Tennessee, which popularized the song in the 1950s and ’60s.

“The royalties go back to the African-American communities from which the song came,” says Pam McMichael, Highlander’s director. “The funds support projects all over the South … benefiting justice and fairness.”

That’s what musician Elijah Wald finds obnoxious about the lawsuit. “What this case potentially does is … defund the civil rights organization that introduced the song,” says Wald, the author of several books on the history of American music.

Rifkin acknowledges the Highlander projects might be a good cause but says that doesn’t justify an invalid copyright. And LiCalsi says, “The song is really being preserved for the integrity of the civil rights movement.”

This article originally appeared in the November 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: "This Song Is Our Song: Lawsuits aim to put iconic folk songs back in the public domain."