Meet the man who would save Guantanamo

Photo of Brig. Gen. Mark Martins by Dave Moser.

For a moment, U.S. Army Brig. Gen. Mark Martins seems discomfited. That is not his nature. In the words of a reporter covering the revamped military commissions now trying accused terrorists in Guantanamo Bay: “Don’t play poker with the man. He has no tells.”

But Martins is visibly stung when told reporters gripe that his lengthy, detailed responses to their questions sometimes don’t contain the direct answers they seek. He winces, holding a squint as he mulls the criticism, his sinewy 6-foot-3 frame folded erectly onto a small couch by a coffee table at one end of his office in a nondescript commercial area of Northern Virginia. His response at first develops in the fashion that brings the complaint: “You have to give them the context. We’re not in the same place we were five years ago. So using the same narratives and storylines when you now have a different statute—Congress has weighed in, we’ve had the judiciary weigh in.”

Martins catches himself in midsentence, then continues in a softer voice that trails off in thought: “So. I probably do. I hope they don’t think I’m pedantic. …”

Transparency has been Martins’ mantra, a theme he returns to often since being assigned in September 2011 as chief prosecutor, the sixth in 10 years, for the controversial military commissions in Gitmo.

In their earlier iterations, one chief and several prosecutors have resigned or sought reassignment, some blaming unethical pressures from both military and civilian higher-ups. Martins knows that perception still rules, and part of his job is to proselytize what he sees as a newfound legitimacy for the rehabilitated military commissions, significantly overhauled to carry the burden of justice for those accused in the September 2001 attacks on New York and Washington and the 2000 bombing in Yemen of the U.S.S. Cole.

But legitimacy is as elusive as it is necessary because of the recent history of military commissions. Dusted off after 60 years of desuetude only a month after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, too much of their modern development took place in the dark underbelly of fiat, political intrigue and utter disregard for justice and the rule of law. Even teachers in the law department at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, Martins’ alma mater, say the system had been reverse-engineered to get hasty convictions and the certainty of executions.

Martins acknowledges that those earlier iterations were seriously flawed, and he has been intimately involved in their reformation. Martins served as executive secretary and co-chair for the interagency Detention Policy Task Force, a U.S. Defense Department group that developed the policies later adopted in the Military Commissions Act of 2009. The legislation attempted to address a variety of criticisms, from the principled stands of civil libertarians to the rebuffs from federal district and appellate courts, and even critics avow the sincerity of Martins’ efforts.

Jennifer Daskal, a fellow at Georgetown University’s Center on Law and National Security, was the senior counter-terrorism counsel at Human Rights Watch when she was hired to work on the task force. Daskal feels that Martins “not only took my views seriously, but actively sought them out and was always incredibly considerate and respectful.” Still, she and those of similar mindset represent Martins’ most formidable audience: She believes the cases should be tried in Article III courts.

“It’s hard to divorce the current military commissions from their history,” says Daskal. “The system is hugely improved, certainly since [earlier versions in] 2001 and including 2006. But with public perception domestically and, more important, internationally, there are huge hurdles for him to overcome. With that said, if the goal is to make the prosecution as fair and transparent and as consistent with the rule of law as humanly possible, Mark Martins is probably the best person for the job.”

Photo of Brig. Gen. Mark Martins by Dave Moser.

SCHOLAR SOLDIER

Any appraisal of Martins, 52, begins with a discussion of his bona fides, which rise above even those of the rarest warrior-lawyer.

In 1983 Martins graduated first in his class of 833 at West Point. Commissioned as a second lieutenant in the infantry, he headed to Oxford University as a Rhodes scholar. While others might have spent the break between them in the tow of Fodor’s England travel guide, Martins squeezed in 61 daunting days of the elite Army Ranger School.

The Ranger regimen pushes soldiers to their limits psychologically and physically, and the washout rate usually is more than 50 percent. A week or so before beginning classes at Oxford, Martins received the coveted Ranger tab on his sleeve.

He graduated from high school in Rockville, Md., just outside Washington, D.C. His father, a colonel, was chief of neurosurgery at the Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Martins met some surgeons on the staff who were West Point grads and found interest in the academy.

“I was a suburban kid,” he says. “Once I got to West Point, now I was orienteering, shooting, mountain climbing, parachuting and doing all of that with buddies,” he recalls. “I love this stuff.”

He runs at least five miles each day and typically sleeps four or five hours a night. Friends say he has been known to self-enforce sleep deprivation at home on weekends to extend his ability to maintain mental acuity without sleep. “It’s like a muscle,” he says, as though that might explain.

The Oxford program is a mix of politics, philosophy and economics, but Martins found himself drawn to studies in jurisprudence. After graduating with first-class honors, he returned to the infantry but after two years entered the service’s Funded Legal Education Program as an Army captain at Harvard Law. Martins graduated magna cum laude in 1990 and was on the law review.

To the extent that authoring particular law review notes might reveal one’s politics, Martins’ writings might illuminate him to philosophical foes. He criticized the U.S. Supreme Court for its handling of Teague v. Lane, which dismissed a habeas petition by a black man challenging prosecutors’ striking of 10 blacks from the jury pool and getting an all-white jury. And Martins wrote that, in Evans v. Jeff, permitting a requirement for waiver of attorney fees in settling civil rights class actions wrongly removed incentives for lawyers to take such cases.

Martins has straddled a sharp divide in the military, in which there is an “operational army” and an “institutional army.” The former includes the armies, corps, divisions, brigades and battalions that carry out military missions around the world. The institutional army, part of which is the Judge Advocate General’s Corps, provides the necessary infrastructure. As the Army’s webpage puts it: “Without the institutional army, the operational army cannot function. Without the operational army, the institutional army has no purpose.”

Martins is well-seasoned in both. But when asked about his various assignments in the operational army, Martins’ instinctive humility subsides a bit. “Since Harvard Law, I’ve been able to spend more time in the operational army than a lot of my brigadier general peers who went into combat arms,” Martins says. “That’s the way it worked out. I’m pretty lucky.”

In 1998, then-Maj. Martins was the first (and, thus far, the only) JAG lawyer awarded the “White Briefcase” as the top graduate of the Army Command and General Staff College, a one-year resident graduate school for grooming top leadership prospects. It’s actually a .45-caliber pistol mounted under glass in a small wooden case, and its other recipients include Gens. Dwight Eisenhower and David Petraeus, Martins’ friend and mentor.

As a lieutenant colonel while he was the JAG lawyer advising the Army’s 1st Armored Division in Iraq in 2003, Martins was tapped to command a 60-vehicle convoy going 400 kilometers over nearly 19 hours from Kuwait to Baghdad—a decidedly dangerous and nonlawyerly mission. Before that, as a major, he was chief of staff providing options in tactical and strategic decision-making (not as an advising lawyer) to the general leading a peacekeeping mission in Kosovo in 1999.

Since 9/11, Martins has been deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan for about 4½ years, including two years at a time in each. He was away from his wife, Kate, herself a West Point grad and former Army helicopter pilot, and their children, who were then in high school. Their son, Nate, graduated from West Point last spring and headed to Ranger School, while daughter Hannah is in ROTC at Princeton University.

Brig. Gen. Mark Martins: “Except for yours truly, this is such an impressive legal team. The partnership we’ve forged between the defense and justice departments serves the American people exceptionally well.” Pictured left to right are: Omar Qudrat, Marine Capt. Michael Krouse, Alan Ridenour, Danielle Tarin, Navy Lt. Jaspreet Saini, Brig. Gen. Mark Martins, Air Force Col. Michael O’Sullivan, Courtney Sullivan, Haridimos Thravalos and Mikael Clayton. Photo by Dave Moser.

ACCOLADES FROM ABOVE

When Martins commanded a large counterinsurgency operation helping develop local legal systems to lessen Taliban influence in the far reaches of Afghanistan, his boss, Vice Adm. Robert Harward, a Navy SEAL, wrote in his evaluation: “Tremendously fit, infectiously successful, visionary yet practical, caring toward his troops and always leading from the front, this is the first officer I would pick for the hardest commands and the most important fights.”

In an evaluation of Martins’ earlier work in Iraq, U.S. Air Force Gen. Richard B. Myers quoted Petraeus as saying Martins was “the most outstanding officer with whom I ever have served—bar none.”

“He’s fiercely competitive, but at the same time he lacks the arrogance that someone with his intelligence, education and background might justifiably display,” says Darrel Vandeveld, who studied international law under Martins at the Judge Advocate General school at the University of Virginia in 1994. “At heart, he’s a very humble person.”

Martins was handpicked to lead the Guantanamo prosecutions by Jeh Johnson, then-general counsel at the U.S. Defense Department, who had seen his work on the Detention Policy Task Force. It was Martins’ experience at dealing with detention problems and rule of law efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan that led to that job.

If Martins’ personal accomplishments have propelled him through the ranks, many believe his personableness and reputation for trustworthiness give him the best hope for his current, unenviable task. And reluctant critics like Daskal and Vandeveld speak to some of the best examples of that.

Vandeveld, now retired as an Army Reserve lieutenant colonel, resigned as a prosecutor at Gitmo in 2008, upset after finding that discovery had been withheld from the defense in a case he was handling. The defendant, Mohammed Jawad, was a teenager when first brought to Guantanamo. Vandeveld came to believe that Jawad was probably innocent, and that he had been subjected at Gitmo to the “frequent flyer program,” in which he was awakened every three hours and moved to different cells for weeks at a time.

Superiors rebuffed Vandeveld’s desire to plea-bargain. In 2009, Jawad was released after a successful habeas petition.

Vandeveld’s noisy exit included testifying in 2009 against the legislation for reformed military commissions. But last year, after Martins contacted him, Vandeveld wrote an opinion piece on the Lawfare blog reversing his position. He cited a mix of admiration for Martins’ professionalism, sufficient fairness built into the revised system and the need to provide long-delayed justice to the defendants in what, at this point, is “the only legal array we have to end a decade of panicky missteps and failure.”

It is difficult to get Martins to toot his own bugle; he’s quick to emphasize the team aspect of whatever he’s doing. Indeed, while he has argued in court in recent hearings when matters touched on the commissions’ legitimacy, the substantive prosecution is being done by others, such as Robert Swann, a retired Army colonel who was chief prosecutor in 2004, and Edward Ryan, who joined the 9/11 prosecution team in 2007 after lengthy experience as a federal prosecutor and more than 100 RICO convictions involving Colombian drug cartels.

While many see the military commissions as intertwined with their complicated history, Martins is driven to legitimizing his prosecutorial task. As the new round of commissions convenes, the ultimate outcome may have a good deal to say about a far broader issue: whether the proper democratic response to terrorism in some instances is found in civilian law enforcement or by military means.

No one wears military uniforms in Martins’ office in Northern Virginia. The building resembles others along block after sprawling block of suburban business-park development. There is a guard desk just outside the elevator on his floor in a reception area so plain and bare, it strongly hints at governmental presence. At either end heavy, locked metal doors lead to the prosecution team’s offices.

Martins, wearing a dark-blue business suit, emerges to greet a guest rather than sending a staffer. He is known for the personal touch and for charm offensives. There is a clear-domed, rotating light on the hallway ceiling outside his office door that flashes red when there’s need to signal “Do not disturb.”

But he is clearly disturbed as he thinks out loud about complaints over his handling of news conference questions. After all, he says, reporters have benefited significantly from the changes he helped engineer.

For example, reporters now can watch Gitmo proceedings on live video feed to several U.S. locations if they choose not to travel to the military base in Cuba; even down there, they are somewhat freer to move about than before. (Their view, though, is through Plexiglas, and they complain about the extraordinary, censor-driven delay in audio. A lawyer’s gesture occurs a clumsy 40 seconds before the words that accompany it.) Same-day transcripts are usually available online. Documents are put up as soon as possible, though it often takes weeks because various federal agencies must vet them for classified information.

Still, it is the issue of torture, not credentialed press logistics that will ultimately determine the fate of the new commissions.

David Nevin, Mohammed’s Attorney: “My question is, when is it OK to use statements they uttered after being waterboarded? …Khalid Sheikh Mohammed [was waterboarded] 183 times in March 2003. Is it OK a day later, a week, a month, a year? When?” AP Photo/File

It is no secret that a number of defendants were tortured or coercively interrogated by the CIA at “black sites” abroad before being brought to Gitmo in 2005. And under some circumstances evidence obtained by torture, “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment” or other coercion can be admitted—though Martins insists he will not avail himself of that.

But the trials under way sometimes look like a game: the defense trying to make the proceedings all about torture, and the prosecution trying to keep any utterance of the word out of the courtroom.

Martins has said the prosecution will not use evidence derived from torture, but defense lawyers and others say the government will bootstrap coerced admissions using similar statements taken later by other, noncoercive interrogators. The prosecution has a different perspective: a “clean team” of FBI agents at Guantanamo later spoke with the detainees in relaxed settings. The clean team spent months being friendly and solicitous with the men, building rapport before questioning them. To defense attorneys, this is a distinction without a difference.

“My question is: When is it OK to use statements they uttered after being waterboarded?” says Boise, Idaho, attorney David Nevin, a lawyer for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the self-admitted mastermind of 9/11. “It’s unclassified, so I’ll say this: Khalid Sheikh Mohammed [was waterboarded] 183 times in March 2003. Is it OK a day later, a week, a month, a year? When?”

Finding that bright line in all this will be up to the judge, Army Col. James Pohl, who is handling both the 9/11 and U.S.S. Cole trials. He will determine whether the FBI agents, if brought in to testify, picked poisoned fruit from the CIA’s tree.

Martins points out that Pohl already has shown independence and resolve in speaking truth to power: He prohibited the Bush administration from razing the notorious Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq on grounds that it was a crime scene; he similarly refused the Obama administration’s request for a stay in the Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri case (the Cole bombing) while a task force studying new approaches to Gitmo was under way. Pohl required dismissal without prejudice.

Beyond that, the prosecution has another avenue to present such evidence. On Feb. 29, 2012, Majid Khan, a well-spoken man whose command of English reflects his having grown up in the Baltimore area, entered a plea agreement on conspiracy and murder charges. Now 32, he had been held in detention for nine years—after his 2003 arrest in Pakistan—before being formally charged just a month before his plea. He is expected to testify against Mohammed and others, and will not be sentenced until after their trial. Thus, mention of the fact that he, too, was tortured won’t occur until then.

©Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis

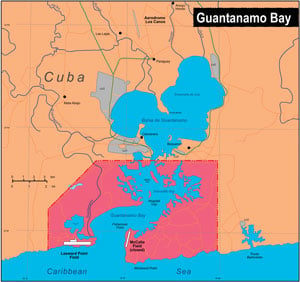

©Maps.com/Corbis

WHAT STAYS CLASSIFIED

Reporters and defense attorneys alike complain of the overclassification of information, especially when it concerns the treatment of detainees. Courts have ruled it improper to do so solely to avoid embarrassment to the U.S. or to conceal illegal activity. But it is the CIA, not the courts, that determines what is a secret and what is not.

Until Martins pulled back the parameters in early September, any utterance by any of the defendants, even telling their lawyers what they had for lunch, was presumptively classified. For two months in 2010, for example, a note from one defendant to his lawyer remained top secret while the government vetted it. It said professional basketball player LeBron James should apologize to the citizens of Cleveland for having jumped to the Miami Heat. Classified information for the trials now is limited to anything having to do with “sources and methods” of interrogations before the defendants’ arrival at Gitmo. Still, critics complain that those interrogations took place eight to 10 years ago, and that the government says coercive practices are no longer permitted. So why the need?

“From where I sit, they’ve structured the entire environment so that the government can talk about the bad things the defendants did, but the defendants are not allowed to defend themselves in any meaningful way,” Nevin says. “The result is a system designed to guarantee convictions and minimize the possibility that anything of substance will come out about torture.”

Nevin—founding partner of Nevin, Benjamin, McKay & Bartlett—has a storied history of challenging what he sees as governmental overreach: In 1993 he won acquittal on all charges for one of two men accused of killing a U.S. marshal during a siege and shootout at Ruby Ridge, Idaho. In 2004 he persuaded an Idaho jury to acquit Sami Omar al-Hussayen, a Saudi student accused of recruiting terrorists. Nevin wants to argue, in part, that the conspirators planning the 9/11 attacks sought retaliation against the U.S. for its own actions against their people.

Harvard professor Jack Goldsmith says, “One aim of defense counsel in high-profile cases like these—and this is what they sometimes do in our civilian courts also—is to try to delegitimate the whole system.”

A friend and admirer of Martins’, Goldsmith resigned as head of the Office of Legal Counsel under the Bush administration, in part over that administration’s justifications for mistreatment of detainees. Goldsmith says critics of the military commissions haven’t thought through the consequences. “The alternative to military commissions for the people being tried in them is not to set them free,” he says. “The alternative is military detention, which puts a lower burden on the state. I think it’s self-defeating for critics just across the board to be against the military commissions when they are a legitimate tool, and when they should see the alternatives as worse.”

As critical as Nevin is of the prosecutions, he sees Martins as a principled force behind them. “The government [still] hopes to execute them and extinguish the only eyewitnesses to the events, the only ones who have any motivation to tell the truth about what happened,” Nevin says. “I find Gen. Martins to be an intelligent and honorable guy. If I had to guess, I’d say he has inherited some limitations in the ways he can go forward that are achieving the effect of the ends I’ve described.”

Martins, in his combat uniform, checks on troop living conditions at a partnered police station in Afghanistan.

HANDPICKED PROSECUTOR

Meanwhile, Martins has been spending a lot of time onstage, often on camera and usually in dress uniform, trying to live the transparency he preaches.

“Gen. Martins has done distinguished work and he’s taken what I think is a thankless task, all to his credit,” says Eugene R. Fidell, a visiting lecturer at Yale Law School, former Coast Guard JAG and an expert in military law. “But he also has felt impelled to spend a lot of time defending the system. You have to wonder why so much effort has been spent justifying its existence when we already have a fabulous judicial system.”

Some see it as double duty. “Gen. Martins and his team are essentially going to have to try two cases in every one case they do because they will be trying to convict a defendant and trying to legitimize their system,” says David Raskin, who just a few years ago was himself readying to try Mohammed in federal court in the Southern District of New York. “That’s twice as much work.”

Raskin is one of many critics who believe the cases should be in federal court. For him it also is a personal disappointment. After 12 years as an assistant U.S. attorney, the last 4½ of them as chief of that district’s terrorism and national security unit, he lost his opportunity to prosecute the worst of all terrorists when President Barack Obama abruptly renewed the military commissions in 2009.

Raskin, who joined the New York City office of London’s Clifford Chance to do white-collar criminal defense, believes military commissions require extra effort in matters that Article III courts already handle in stride. Hundreds of terrorism cases have already been prosecuted in our federal courts, a criticism Martins knows all too well.

“We don’t seek to displace the federal courts in international terrorism cases,” Martins says, “but there is a narrow category of cases where counterterrorism professionals, prosecutors, intelligence and law enforcement officers might determine that the best forum is a military commission.”

Criteria include point and circumstances of capture, foreign policy concerns, evidentiary problems, and the nature and gravity of the conduct. If there are violations of the laws of war, more serious matters might be better handled by military commissions if certain other factors come into play, too. One of those, as Martins has put it in some of his speeches, “is the manner in which the case was investigated and evidence gathered, including which entity conducted the investigation” and a particular forum’s capability for protecting “specific intelligence sources and methods.”

Some critics turn that argument back on itself. “In these cases the government is trying desperately to avoid their own shadow, from abusing detainees,” says Stephen I. Vladeck, a law professor at American University and regular contributor to the Lawfare blog. “Not that it changes the terrible crimes the defendants committed. That’s the tragic irony.”

But Robert Chesney, a professor at the University of Texas law school, believes military commissions have become a proxy in the debate over the U.S. approach to battling terrorism. “The commissions have a profoundly significant symbolic value for both sides,” says Chesney, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution. “If you step back from the debate, people who want military commissions are that way not so much because they believe them to be better than civilian courts; they want a symbolic statement that this is a military concern, and they are opposed by most on the other side for that same reason. I’m not saying Mark Martins and others have this view. But it drives the narrative.”

Martins thinks the context of terrorism is too complicated for Manichean choices: “I don’t identify with either side, but we do face serious and adaptive yet entirely surmountable threats from irregular, nonstate groups—an attack can be characterized as both an act of war and a crime. Seeing military and law enforcement responses as mutually exclusive is a false choice. And lawfully gathered, noncoerced evidence in armed conflict should not be subject to identical rules of admissibility in a criminal trial. With that said, there is of course a critical role for law enforcement, and I believe our federal courts should continue to be our primary venue.”

For Martins, military commissions aren’t just the only game in town—they are the only possible one for now. Since 2009, to thwart Obama’s then-stated desire to close down detention and trials at Guantanamo, Congress has issued successive legislation prohibiting the use of any government funds to bring detainees onto U.S. soil from Gitmo.

“I want to push back the notion that military commissions are what you use when you can’t prove the case in federal court,” Martins says. “It doesn’t work that way. This has to be a public trial; it has to exclude coerced evidence and provide counsel rights. I’m going to present cases based on admissible evidence, and that’s also not classified. The accused and counsel can litigate admissibility and refer to matters that relate to prior treatment. It is wrong out there to say we are attempting to sidestep relevant matters.”

Chesney offers a counterfactual explanation for how things might have worked out better: “If in 2001 we’d had the 2009 Military Commissions Act and Mark Martins in charge of the prosecution, from the get-go there would have been significant focus on the legitimacy of the system, rather than on the more draconian-looking, multiyear process we got. I’m sure some would still be critical, but it would not have become the cause célèbre it continues to be.”

The facts on the ground are, of course, very different, and the military commissions remain under siege as they have been for years, even as they proceed.

Martins, meanwhile, adheres to the Army’s colloquial maxim, often barked by sergeants, which could apply from firing ranges to mess halls to command positions: “Stay in your lane.”