The Hacktivists: Web Vigilantes Net Attention, Outrage and Access to Your Data

Illustration by Stuart Bradford

Law firms, security experts, international law enforcement agencies, major corporations and even the FBI are wrestling with a hard realization these days: From the darkest reaches of the Internet, a strange sort of “law” has come to town, and its name is Web vigilantism.

The tools of these “enforcers” are not new: Distributed denial-of-service attacks, website vandalism, hacks into stored information, and release of secret documents and personal data have all been used by computer-savvy intruders having fun, individuals expressing a gripe, protesters pressing a cause and criminals seeking illicit gain.

What’s new is a public bravado and political stance taken by the new vigilantes, or hacktivists, as some call them.

Among the most celebrated (and feared) of such groups is the one known as Anonymous, a loosely associated assemblage of hacktivists that gained national media attention claiming that had it disrupted business for some of the biggest corporations online. Much U.S. coverage dealt with Anonymous denial-of-service attacks in defense of Julian Assange and the WikiLeaks release of secret U.S. government emails.

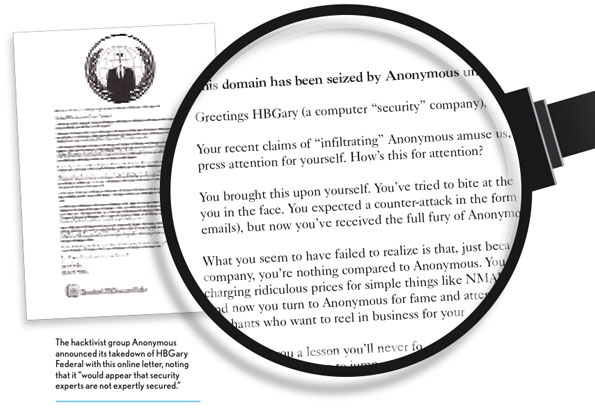

Less known in the States is how Anonymous allegedly brought a computer security firm to its knees, tainted the career of the firm’s now-former CEO, hung the company’s law firm client out to dry—and so far has gotten away scot-free.

“Anonymous is heroic to many people who are sick of government lies and weary of government intrusion —unwarranted and warrantless—into the lives of U.S. citizens,” says Sharon D. Nelson, president of Sensei Enterprises, a legal IT/computer security firm in Fairfax, Va.

“They have become very much like, in the Terminator movies, the resistance fighting Skynet,” she says. “Many are script kiddies, or amateur hackers. But there is a core group of hackers who have extraordinary skills. They present one of the greatest security threats of recent years. And we have not, so far, done a lot to counter their intrusions.”

CYBERSHREDDING

As many law firm security experts know all too well, the computer security firm whose reputation was shredded by Anonymous was HBGary Federal, and the incident raised serious questions about the activities of major law firm Hunton & Williams.

The techno-vengeance was claimed as a pre-emptive strike by Anonymous, triggered by threats from HBGary Federal’s then-CEO Aaron Barr, who had boasted to the Financial Times that he knew the names, identities and addresses of key members of the group and planned to publicly reveal them to law enforcement and others at a computer security conference.

Within days Barr’s firm saw its website compromised and email database raided. According to press reports, Anonymous announced that the firm employees’ passwords were changed, a server was wiped and its landing page defaced. Before the company could say “goodbye credibility,” more than 70,000 of its private company emails had been published online for all to see.

Besides making a sham of HBGary Federal’s reputation for security, the stolen emails revealed what appeared to be evidence of a plot: Embedded in the electronic communications were exchanges about an alleged campaign of dirty tricks HBGary Federal and two other computer security firms were concocting on behalf of Hunton & Williams. The campaign’s alleged target: StopTheChamber.com, a group opposed to the political campaigns waged by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce on behalf of business interests.

According to the published emails, HBGary Federal and others were planning to discredit and neutralize StopTheChamber.com through the use of an array of dirty tricks, including forged documents, fake social media personas, spyware and malware designed to disrupt computer systems, and a news media disinformation effort.

The alleged beneficiary of all the back-alley work would be the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, a Hunton & Williams client. The chamber did not respond to requests for comment on this matter.

“Allowing cyberconspiracies to attack active citizens and journalists to cower them into inaction is unacceptable,” says Kevin Zeese, a lawyer and spokesman for StopTheChamber.com. Zeese, a longtime public interest activist, says he has filed a formal complaint with the District of Columbia Bar’s Board on Professional Responsibility demanding the disbarment of three Hunton & Williams attorneys named in the stolen HBGary Federal emails as part of the alleged dirty tricks campaign.

“The actions of the H&W attorneys in this case constitute very serious violations of the disciplinary rules and very likely also violate both state and federal criminal statutes,” Zeese says. “We have asked for a criminal investigation of this matter.”

The board, as a matter of policy, does not acknowledge the existence of any ongoing complaint in process, according to Wallace “Gene” Shipp Jr., bar counsel for the D.C. Bar. Hunton & Williams did not respond to requests for an interview for this article.

But U.S. Rep. Hank Johnson, D-Ga., has questioned whether HBGary Federal and two other computer security firms may have violated federal law in one of the alleged plots by proposing the use of malware developed under government contracts for the U.S. military.

Johnson sent requests (PDF) for copies of those contracts to the U.S. departments of Defense and Justice, and the director of national intelligence. Although Johnson has received most of the requested information, appropriate U.S. House committees have declined to hold hearings on the matter, according to Andrew Phelan, Johnson’s communications director.

“This scandal cries out for a full investigation,” Johnson says. “I am concerned about this case and the way it’s being swept under the rug.”

In April, HBGary published an open letter on its website, distancing the company from Barr. The letter took great pains to assert that HBGary and HBGary Federal were two distinct companies, and that the former company was in no way involved in Barr’s alleged plans.

“HBGary Inc., the COTS [commercial off-the-shelf] software company, was not involved in Mr. Barr’s research or his proposals for social networking surveillance,” the letter stated. “Rather, HBGary Inc. was a victim of circumstance, caught within the storm of a vengeful retribution attack against Mr. Barr for his claim that he had infiltrated the hacking group. In short, HBGary Inc.’s emails were compromised merely because it shared the same cloud-based email system with HBGary Federal.”

The letter is no longer accessible online, and a request for access drew no response.

Amid all the scandals, tainted careers and sheer humiliation, perhaps most disturbing for law firms and the business community at large is that Anonymous was able to devastate the defenses of a computer security firm so easily—and that after months of investigation, not a single hacker associated with the HBGary Federal break-in was identified, although there have been arrests of alleged Anonymous members in the United States and Europe involving similar hacks.

“As cybercrime groups increasingly recruit experienced actors and pool resources and knowledge, they advance their ability to be successful in crimes against more profitable targets and will learn the skills necessary to evade the security industry and law enforcement,” Gordon M. Snow, assistant director of the FBI’s cyber division, told a U.S. Senate Judiciary subcommittee on crime and terrorism in April. “The threat has reached the point that, given enough time, motivation and funding, a determined adversary will likely be able to penetrate any system that is accessible directly from the Internet.”

Photo by Sklathill’s Photostream

CAUSE, NOT CASH

What helps make Anonymous baffling and unpredictable to law firms and security experts is that the group is not driven by avarice. Its image is one of a shadowy hodgepodge of technologically gifted wunderkinder who crave the ultimate goof with a take-no-prisoners attitude. And increasingly, their skills are being directed in support for the latest cause célèbre.

“The truth is, Anonymous isn’t primarily an evil computer intrusion gang,” says Kevin Poulsen, news editor at Wired.com in San Francisco and a notorious former hacker in his own right. “Most of the time it’s an unorganized collection of apolitical pranksters who are sometimes good, sometimes evil, and mostly don’t care.

“Occasionally a large number of Anons will coalesce around an ideological cause, like defending WikiLeaks, or a couple of years ago attacking Scientology. But once these campaigns stop producing laughs—“lulz”—you invariably start seeing grousing among the Anons that they’ve lost their way.”

Ira Winkler, founder of the Baltimore-based computer security consulting firm Internet Security Advisors Group, has a similar perspective. In many ways Anonymous reminds him of an infamous group of hackers prominent in the mid-’90s, the Gray Areas Liberation Front. As with Anonymous, it was tough to know what to make of GALF, which many perceived as subversive, ominous and fathomless.

Others, including Winkler, were considerably less awed. “Frankly, somebody would just say, ‘I’m bored, I wanna hack something,’ and they’d put the GALF label on it,” says Winkler, who made his bones in digital intelligence during an eight-year stint at the National Security Agency before setting up in the private sector. “And then somebody else would get bored and put a GALF label on that. And everybody was ‘Ooooh, GALF.’ ” In reality, Winkler believes, the GALF name was itself a ruse, a label hackers pasted on a hack simply to “screw with the media.”

The problem, of course, is that once a group of techno-wizards goes giddy with power, there’s a tendency to see how broadly it can be wielded. In the case of HBGary Federal, for example, Anonymous went beyond simply ravaging the company’s security and publishing its emails on the Web.

It also publicly demanded Barr’s resignation as CEO of the company. And while Barr’s departure was initially described as a leave of absence, the facts speak loudly: Before the Anonymous break-in, Barr was riding high as a crusader ready to vanquish the vigilantes of the Web. After the Anonymous break-in, he was on the sidewalk.

“When you proclaim yourself to be one of the country’s leading information security companies, you are begging hackers to take a whack at you,” says Sensei’s Nelson. “And when you give them a reason, you can be sure they will. [HBGary Federal’s standards] were so out of compliance with industry best practices that it defies belief.”

Adds Winkler: “What Aaron Barr did was pretty much proliferate the nonsense.” Instead of quietly forwarding the Anonymous identities he said he possessed to proper authorities, Barr announced to the world that he would release the names with great fanfare at an upcoming computer security conference, Winkler says.

“The greatest irony is that after all of this stuff, apparently he didn’t have any real information,” Winkler says. “Because if he had real information, he could have helped put ’em in jail.”

SECURE YOURSELF

The Anonymous raid on HBGary Federal should be a cautionary tale for law firms on the realities of cybersecurity. Firms need to understand that the threat won’t be neutralized anytime soon, and they need to fess up that their current computer defenses are probably Silly Putty in the hands of the experienced hacker.

“It is difficult to argue that attorneys should not be required to provide at least the level of protection required for banking, credit card, health and similar kinds of personal information,” says David G. Ries, a partner at Thorp Reed & Armstrong in Pittsburgh.

But these businesses can also take some measure of comfort in knowing that HBGary Federal was hacked because its leaders ignored some of the most basic tenets of their own security industry.

For instance, their content management software was custom-made. Such programs are rarely subjected to the rigorous security testing that popular, established software endures.

Custom-made content management systems are a bad idea, Nelson says. “Either [HBGary Federal] did no independent assessment of the CMS security or they inexplicably missed a gaping bug.”

Then there were the passwords. Many security companies recommend complex alphanumeric passwords of more than 12 characters, which are tough to crack—even by password-stealing software. Moreover, they recommend a change of IDs and passwords as you pass through various system gateways. HBGary Federal apparently didn’t bother.

“Barr and COO Ted Vera used passwords of six lowercase letters and two numbers—easy as pie to compromise,” says Nelson. They “used the same password in numerous places, so once the hackers had the password, they could get into social media accounts and email, for instance.”

And while security firms warn others about the dangers of “phishing” and “social engineering,” Anonymous was able to get an HBGary Federal trading partner to give up the ID and password for its website using a woefully unoriginal email ruse.

After breaking into the email account of Greg Hoglund, co-founder of HBGary, the hackers sent an email from Hoglund’s account requesting the company’s website ID and password. On the receiving end was Jussi Jaakonaho, chief security specialist at Nokia.

“Jussi fell for it, surrendering the critical information they needed,” Nelson says. “How could he believe that Greg had forgotten both his password and his ID? He should have been more suspicious and been wary of handing credentials out via email.”

NO JOKE

Long term, the real worry over Anonymous may hinge on whether the group’s increasing predilection to lend its tech skills to popular causes morphs into its core identity. There was nothing funny about the Anonymous decision to attack Visa, PayPal and Master Card in connection with the WikiLeaks data release, at least for those on the receiving end. Instead of simply goofing around, Anonymous has caused real damage in the name of ideological belief.

It’s enough to give pause to any law firm rep resenting a client caught in the crosshairs of public controversy. If the computer systems of Internet goliaths are child’s play for idealistic digerati, what chance do small, medium or even large law firms have?

“There are so many folks disaffected with government and corporate lies,” says Nelson. “This group and others like it are likely to thrive in a world where lies can be exposed electronically. It was actually much tougher in the paper world.”

Adds former hacker Poulsen: “The battle over WikiLeaks has exposed a cultural divide between two groups who both think the Internet belongs to them—large corporations on one hand and a generation that grew up online on the other. I think if ideological hacking really takes off, a lot of organizations are going to look like old-growth forests about to see their first lightning strike.”

One thing working for investigators, if fitfully, is that large-scale computer attacks against large corporations like those launched against Visa and PayPal often leave behind scores of digital fingerprints from thousands of less-savvy, wannabe hangers-on. Such digital trails have led to international arrests related to those hack attacks.

The Visa campaign, which overwhelmed the corporation’s website with simultaneous requests for downloads of its home page, could not have been done without an army of tens of thousands of drone computers. And in the case of that Visa onslaught, a denial-of-service attack, those drones can be easily identified, Winkler says.

Truth be told, Anonymous made no secret of its intent to bring down Visa’s home page, Winkler says. It very publicly posted a malware tool on the Web that, once downloaded, transformed an individual’s PC into a drone primed for havoc. And tens of thousands of people downloaded the malware, knowing full well their PCs would be transformed into mindless digital soldiers programmed to butcher corporate websites, Winkler says.

Even more unbelievable, Anonymous made no effort to hide the digital tracks leading back to the PCs that helped the group pummel Visa, according to Winkler. “If law enforcement wanted to, they could have gone out and arrested literally thousands of people. If they had the will to do it, they could have vac uumed up a whole bunch of people for doing incredibly stupid things.”

The upshot? As Anonymous leaps from one escapade to another, a disturbing message is emerging, according to Winkler: Hacking, no matter how destructive, carries no repercussions except in a few isolated cases. That encourages Anonymous to engage in even more outlandish and destructive antics. And it encourages a rash of copycats to lunge for the limelight.

Says Winkler flatly: “There should be enough information to go after people.”

Sidebar

HACKS AND HACKERS

In popular culture, hacking has long been regarded as a kind of impish, even roguish, intellectual exercise.

In the movies, hackers are hunted by cops and evil moguls as they try to steal money or secrets for the greater good. On television, many of them are cops who have no problem finding phone records, bank ac counts or credit card receipts. No one on NCIS seems to need a search warrant.

In reality, hackers are college students, mobsters, vandals, protesters, corporate spies, even journalists. Here’s a small sample of their most notable work.

THE MORRIS WORM: In 1988, Robert Tappan Morris crippled a tenth of the Internet when he released a worm that wreaked havoc on computer systems all over the world. Morris, who had bragged about the effectiveness of his worm on Internet chat sites, was later arrested and convicted under the newly created Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

KEVIN MITNICK: One of the first—and easily the most famous—of the large-scale hackers, Mitnick used “social engineering” to con identities and passwords from high-level computer users. Mitnick made the FBI’s most-wanted list after he bolted while on probation. He’s been the inspiration for several movies about hacking, including WarGames, which describes a hack of the North American Air Defense Command—and one that he steadfastly denies. In 1998, he also inspired another famous hack, one in which intruders defaced the New York Times with a rambling “Free Kevin Mitnick” manifesto.

THE MELISSA VIRUS: In 1999, David Smith created global panic of the computer kind with a devastating email virus apparently named after an exotic dancer. The virus contaminated more than 300 companies across the planet and caused an estimated $400 million in damages to corporate computer systems worldwide.

GOOGLE: In June, the search-engine giant Google announced that hackers had invaded its systems, apparently in search of the accounts of high-level officials. Google said it believed the highly coordinated attack came from the Chinese government, a charge the Chinese angrily denied. It claimed the intruders tried to steal the passwords for hundreds of Google’s Gmail account holders—among them U.S. officials, journalists and Chinese political dissidents.

NEWS OF THE WORLD: In July, one of media mogul Rupert Murdoch’s most successful news ventures, News of the World, was forced to close its doors after allegations that reporters and editors at the paper had been routinely hacking cellphones for news stories. Founded in 1842, the paper was the first and most visible casualty of the scandal, which is still unfolding in the U.K., as well as in the U.S.

Joe Dysart is a freelance journalist and business consultant based in Manhattan. His website is at joedysart.com.