How to pull off a successful law firm merger

Illustration By Jim Frazier

Mergers have become an increasingly popular option for law firms seeking to expand their national or global footprint and to weather the changing legal climate. But determining whether a merger is the right option takes more than due diligence. It requires extreme soul-searching and a laser focus on the long game. To this end, Mayer Brown’s playbook could be considered a case study for a successful merger.

In the last 15 years, the firm has undergone three mergers on three continents, transforming it from a Chicago-based firm with just 3 percent of its attorneys outside the U.S. to a global firm with nearly half its lawyers in foreign offices. The firm’s exponential growth was driven by clients’ increasingly global needs, says Paul Theiss, the firm’s Chicago-based chairman.

The mergers are working just as the firm intended: Recently, Mayer Brown’s outpost in Hong Kong collaborated on a client matter with a new lawyer in the Frankfurt, Germany, office. And it’s worked out for the attorneys, too: Mayer Brown experienced a 47 percent growth in net income and a 35 percent increase in profits per partner between 2012 and 2015.

Broad-scale mergers are not a new business strategy. Back in 1987, for example, legal powerhouse Clifford Chance was born when London firms Coward Chance and Clifford Turner combined. Later, in 2000, Clifford Chance completed a three-party international merger with Germany’s Pünder Volhard Weber & Axster and New York’s venerable Rogers & Wells. Similarly, in 2001, white-shoe U.S. firm Sidley & Austin merged with 400-lawyer Brown & Wood.

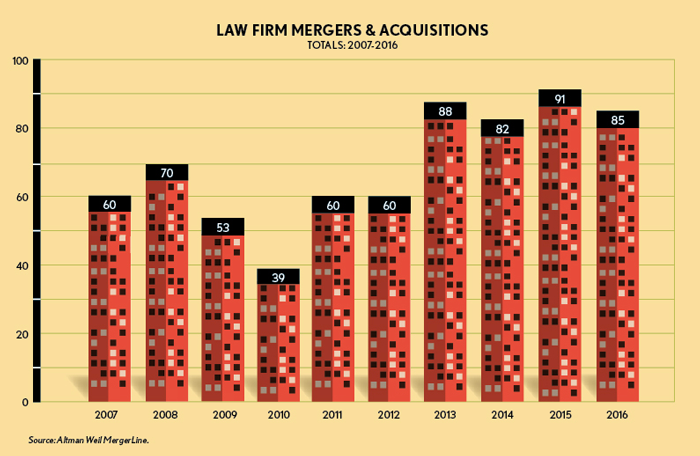

While not a novel tactic, mergers have become much more common since the Great Recession, according to Andrew Jillson, a Dallas-based law firm consultant. “Mergers are a way that many firms are reacting to upheaval in the legal market,” Jillson says. “So there’s been a steady pace upwards.”

According to consulting firm Altman Weil, which keeps a running log of law firm acquisitions on its MergerLine website, 91 law firm combinations were announced in the U.S. in 2015, representing the highest annual total recorded in the 10 years MergerLine has been compiling data. Along with a record number of combinations, 2015 also saw the largest-ever law firm merger when 2,600-lawyer Dentons combined with a 4,000-lawyer Chinese firm, Dacheng Law Offices. In another significant match, DLA Piper acquired firms in both Sweden and Canada last fall.

Sidebar: Not ready for a merger?

THE MERGER STRATEGY

While increasingly popular, merging is not a foolproof business strategy. There are plenty of cautionary tales—mergers that failed altogether, resulting in distress or disaster, or suffered client or lawyer attrition—including those of Bingham McCutchen and Dewey & LeBoeuf.

Indeed, experts agree that a merger should not be an endgame for its own sake. Instead, it should serve a broader business goal. For some firms, that might be reaching new markets or adding practice groups that clients are demanding. For other firms, that might be recruiting higher-caliber lawyers or creating efficiency.

“A law firm merger needs to further a strategic imperative that the firm arrived at in a clear-thinking way, and that imperative should not just be growth,” Jillson says. “If you don’t approach a merger correctly, you can just end up adding more weight to the firm in a way that doesn’t further any strategy.” Firm leaders should determine what they’re trying to accomplish “before the mating dance starts,” he says.

Achieving practice group, industry or geographic synergy—“filling in some holes”—bodes well for a strong merger, says Peter Zeughauser, a management consultant based in Newport Beach, California. “Nobody can hire you if they’ve never heard of you,” Zeughauser explains. “Data supports the notion that the more breadth and depth a firm has, the better known you will be. A firm’s size, relative to market, strengthens the brand. You need to be big relative to your market and ‘market’ is practice, industry or geography.” So a top IP firm in Los Angeles doesn’t need to be 1,000 lawyers, for example, but it may need to be 100 lawyers. “A merger can help you build breadth and depth more efficiently because it’ll be quicker and cheaper than building through lateral hires.”

When Bradley Arant Rose & White, a 250-lawyer multi-office Alabama-based firm, merged with midsize Nashville, Tennessee, firm Boult, Cummings, Conners & Berry in 2009, there were “two overriding rationales,” says Beau Grenier, chairman of Bradley Arant Boult Cummings, now a 500-lawyer firm. “The way the industry was moving, having a more geographically diverse firm better positioned us in the market to serve and attract clients. So the business case to becoming a super-regional firm was compelling. Also, specific synergies between the two firms made that business case even stronger.” In particular, one legacy firm had health care clients but not many health care lawyers, whereas the other legacy firm had the opposite, Grenier says. Since the merger, revenue is up about 65 percent. Also up are profits per equity partner and the number of client matters imported and exported among the firm’s now nine offices.

Like Mayer Brown and Bradley, other firms have successfully completed mergers in recent years, including Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer, Bryan Cave, Hogan Lovells, Reed Smith, Sidley Austin and Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr, to name a few.

Paul Theiss At Mayer Brown, “we rise and fall together as a partnership. It creates the right incentives.” Photograph by Wayne Slezak.

Despite this record of successful industry mergers, firms must pursue acquisitions with “a high level of discipline,” Jillson advises. Firm leadership must define criteria that will guide them and then remain faithful to that criteria through the process. A merger, adds firm management consultant John Olmstead in St. Louis, “is a very serious thing.” It must not be “a knee-jerk decision that’s all about the short term, all about money.”

Experts offer specific tips for the process of merging once a firm decides the approach is in its best interest. Brad Hildebrandt, a New Jersey-based law firm consultant, suggests keeping preliminary meetings between the two firms small. “Usually, it’s just me and the two law firm chairs,” Hildebrandt says. “Later, we include the two executive committees and then key practice group leaders. After that, it’s a delicate balance. You have to put it out there [to the wider firm] or you have a timing problem. If you’re quiet too long, the partners at large may revolt.”

But before spending months and months on a merger, Hildebrandt says leaders should work quickly to resolve potential deal breakers. First and foremost, firms must look very early for conflicts, particularly business conflicts in which the two firms represent clients that compete with each other. “Most mergers that don’t go anywhere are because the firms waited too long” to iron out conflicts, Hildebrandt says, citing as an example a doomed merger between Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman and Orrick Herrington & Sutcliffe.

Even if conflicts are overcome, sometimes merger talks fail for more personal reasons, Hildebrandt adds. Partners can have an extreme emotional attachment to the legacy firm, making them unable to get behind a new combination. “Partners’ egos get in the way,” he says. “Plus, there’s always the infamous discussion about the new firm’s name. No one wants to be second. My advice? Put off the name discussion a little bit. Let people get excited about the merger first.”

That said, law firms must also have the discipline to end discussions when necessary. “You can’t get so invested in the thrill of the pursuit that you make a bad decision,” Jillson says. “You need to be able to say, ‘This looked like a good deal, but we need to walk away.’” Danger signs include firms that seem desperate to merge or one firm that tries to out-negotiate the other. Another potential red flag: Firms that have recently acquired a slew of lateral attorneys can easily lose those same lawyers because they’ve got experience packing up their practices and heading out the door.

Once discussions are underway, Jillson’s primary advice is to “really scrub the compatibility metrics.” That includes everything from finances, clients and operations to culture and strategy.

When it comes to practice compatibility, variables such as the level of sophistication (commoditized vs. bet-the-company matters) and client base (including size and industry) must line up. Does one firm typically represent management while the other represents labor? Is one primarily a plaintiffs firm and the other more defense? How are client relationships established and nurtured?

FISCAL PEACE

Financial compatibility is also essential. A firm’s balance sheet—including debt, spending, distributions and capital structure—reveals its culture, Hildebrandt adds. “These can be sticky points.” In addition to the standard profits-per-partner and revenue-per-lawyer data points, which some argue are easily manipulated, firm leaders should scrutinize billing rates and office leases. Compensation, of course, is a critical facet of a deal. Does one firm use a formula system and the other a tiered system? Is compensation evaluated annually or every two years? Are some partners at one firm guaranteed income?

A uniform compensation system across borders results in a unified firm post-merger, according to Mayer Brown’s Theiss. His firm operates “as one economic partnership around the world,” he explains. “Partners share in a single profit pool at the end of the year. That’s key—we rise and fall together as a partnership. It creates the right incentives. We share responsibility for client service and professional excellence. We’re not small-group silos.”

Rate structure and compensation compatibility are so important that they should be addressed in the first meeting or two between the firms, Olmstead says. “Compensation breaks down a lot of deals. If one firm charges $450 an hour and another $200 an hour, that could be a problem. It’s the ‘qualify your prospect’ concept from sales. Also, determine how partners pay themselves—it’s not just the money but how it works. There’s eat what you kill versus we’re all in this together. Those are two different kinds of worlds.”

Source: Altman Weil MergerLine

Regarding operations, a merger can provide distinct opportunities to establish new best practices. Rather than simply continuing with one of the two firms’ operations, the combined firm should seize the chance to adopt new approaches that are an improvement for both, according to experts. To that end, Hildebrandt recommends moving forward “as if starting a new law firm.” Everything from cybersecurity to governance should be re-evaluated and possibly restructured.

Experts agree that the most important area to ensure compatibility is culture. Both firms “better make sure they really understand the two cultures and whether they fit,” Bradley chairman Grenier advises. “There are always cultural differences between two institutions—you can’t avoid that. But you do need a fundamental understanding” about critical elements such as governance, work-life balance and “how you treat your people.” In Bradley’s case, the two firms spent 18 months talking before the merger closed in early 2009. “By that time, we knew each other really well. It was the lowest point of the economic downturn and the two firms got to go through it together,” Grenier says. “It was tough for everybody but a great bonding experience.”

Even though a merger may make economic sense, talks may still fail because law firms are “very tribal in their culture,” Zeughauser says. “As much as they’re the same, they’re different and differences emerge during merger talks.” Culture includes everything from workload expectations to the client service commitment to staff employment policies. It’s personalities, philosophies and lifestyles. In talking with potential merger partners, “start with the people and the culture first,” Olmstead advises. “Many mergers fail because the wrong people got married.”

TEAM POWER

Once a merger is underway, a transition committee composed of lawyers and staff from both firms should gather input from rank-and-file lawyers and employees. An integration plan with a timetable should be developed as early as possible to avoid stumbling through decisions by default.

“That can sound counterintuitive,” Jillson notes. “Many firm leaders think: ‘Let’s get the deal done and we’ll deal with integration later.’ But it’s smart to be thinking early about how the firms will be integrated. You must dedicate a lot of time post-closing—at least as much as before—establishing processes and procedures. You can’t just flip a switch.”

In Mayer Brown’s case, it became increasingly apparent with each merger that the new partners should be immediately commingled in client teams and practice leadership. “Just as for lateral hires—it’s not good enough to say, ‘Here’s your office, computer and assistant; let us know if you have questions’—the same principle applies to a merger,” Theiss explains. Mayer Brown’s recent Hong Kong-Germany crossover was the fruitful result of new lawyers traveling to different offices to learn about everyone’s expertise and clients. “That builds internal trust and gives a superior level of service” to clients.

Indeed, the real work begins after the transaction closes, Grenier adds. “There’s a whole psychology around how people respond to change. It’s called change management. People feel a certain sense of loss. We know a lot more about that in hindsight.” Being sensitized to that loss can help with “cultural assimilation,” Grenier says. In fact, preserving too much independence—such as keeping the same leaders in the old offices—works against integration. Firm management should also recognize that mergers can sometimes be harder on administrative staff than on the lawyers.

Once complete, a merger’s success may be evaluated at least in part by post-transaction attrition, Jillson says. But Hildebrandt notes that “regrettable and nonregrettable departures” should be distinguished. Some departures “may always have been the plan,” either due to conflicts or previous underperformance, Hildebrandt explains. “Both firms may have already baked in those adjustments.”

In addition to attrition, indications of a problematic merger include weakening financial performance or the loss of major clients. But Zeughauser cautions that a merger’s success may not be immediately gauged because it can take as long as five years for everything to shake out. To that end, firms should be realistic about post-merger economics. “Don’t over-budget revenue in the first year,” Hildebrandt advises. “It takes time. And firms should overestimate merger expenses,” such as technology costs.

Hildebrandt also suggests questioning the combined firm’s partners about the merger’s success. “Are they making more money? Do they have new clients? Have they achieved a main goal: to broaden and deepen the platform?”

One clear measure of a merger’s success is clients who come to believe the combined firm is better able to service their needs, resulting in more matters being sent there. “Consummating a merger is hard work,” Mayer Brown’s Theiss says. “But that’s actually the easier part. The harder part is making it work weeks and months after” and teaching clients about the advantages of a merger. “We explain that the merger provides them with a very strong solution for their complicated problems.”

Correction

Print and initial online versions of “Make Me a Match,” June, should have stated that Mayer Brown has undergone three mergers in the last 15 years.The Journal regrets the error.

Leslie A. Gordon, a former lawyer, is a legal affairs journalist based in San Francisco. This article originally appeared in the June 2017 issue of the