Shook Hardy Smokes 'Em

John Murphy, Gary Long,

Madeleine McDonough, Harvey Kaplan

Photo by Jason Dailey

It was a Perry Mason moment.

The witness, an old man dying of lung cancer, had just finished telling the jury why he could be so sure that Kent was the brand of cigarette he had switched to as a young man almost a half century earlier.

The man was the plaintiff in a closely watched 1995 product liability suit against the tobacco industry. He had been diagnosed with mesothelioma, a rare but deadly form of lung cancer caused primarily by exposure to asbestos. And he blamed his disease on a filter containing asbestos used in Kent cigarettes over a four-year period in the mid-1950s.

The witness said he took up smoking during World War II and that he clearly remembered switching from an unfiltered brand to Kent shortly after it came on the market in the spring of 1952.

Since there was no evidence to support his testimony, his credibility was key.

It was an important time in his life, he told the jury on direct examination. He had just finished school in Kansas and gotten a job as a clinical psychologist and instructor at a university hospital in Cleveland. Kent was heavily marketed as the first “healthy” cigarette. One of the doctors he worked with even recommended them.

And he couldn’t forget the distinctive blue color of the Kent filter, because it was “exactly the same color” as his late father’s beautiful blue eyes.

When it was time to cross-examine the witness, the tobacco company’s lead trial counsel—a young lawyer who looked as if he had never smoked a cigarette in his life—wasted no time on pleasantries. He peppered the witness with questions about his medical history and smoking habits. He asked him about the possible side effects of his illness and his understanding of the role that hindsight can play in a person’s ability to recall events clearly.

Then suddenly he brought up the witness’s description of the Kent filter being the same color as his deceased father’s blue eyes.

“Did your father have brown eyes?” the lawyer asked, producing a copy of a citizenship petition apparently signed by the father when he immigrated to the United States from Austria in 1928. It listed the man’s eye color as brown.

“That’s what it says, but that’s not true,” the witness replied, his own blue eyes welling with tears. “Are you telling me that my father had brown eyes?”

“All I’m telling you is that’s what it says in this petition,” the lawyer responded.

“That’s ridiculous,” the witness muttered indignantly, as the document was offered into evidence. “Are you trying to tell me what [color] my father’s eyes were?”

That made-in-Hollywood exchange was the handiwork of lawyers from the Kansas City, Mo., firm of Shook, Hardy & Bacon. It had all the hallmarks of the firm’s style—the search for any relevant record, no matter how obscure; the tough cross-examination; the coup de grâce delivered at just the right moment. It’s made Shook Hardy the firm many of the world’s biggest companies turn to at the first hint of trouble with one of their products.

And it’s a style of litigation that keeps them coming back, even when, as in the case of Kent-smoking Milton Horowitz, the jury awarded $2 million in damages. The foreman told reporters afterward they had been incensed by the cross-examination of the dying old man.

Fifty years ago, Shook Hardy had a local practice and fewer than two dozen lawyers. Starting with cases for Big Tobacco, it has built itself into a national firm handling all manner of product liability cases. It’s defended everything from pharmaceuticals and medical devices to automobiles, chemicals, consumer products and foods. Shook Hardy’s client list has included Philip Morris, Ford, Microsoft, Pfizer, Bayer and Sprint Nextel.

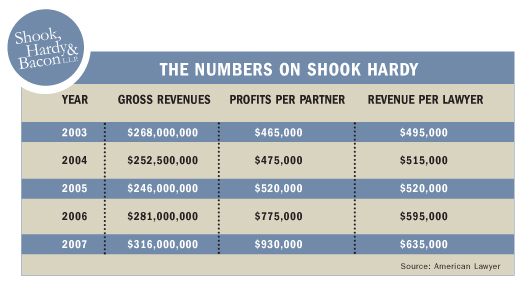

Its growth has accelerated accordingly in the last two decades—increasing from 155 lawyers in 1990 to 509 today. The firm occupies all 24 floors of a sleek new Kansas City tower and maintains branches in eight other cities, including London and Geneva. It had gross revenues of $316 million in 2007 and ranked 67th nationally in profits per partner, at $930,000, up 20 percent from 2006, according to American Lawyer magazine. Part of its appeal, according to its clients, are lower rates than those charged by firms of similar size and experience in larger cities.

With that success—and the manner in which the firm has achieved it—has come the undying enmity of the plaintiffs bar and even some judges. In the 2006 final judgment of the Justice Department’s massive civil-racketeering suit against the tobacco industry, U.S. District Judge Gladys Kessler of Washington, D.C., said the tobacco industry’s lawyers had “played an absolutely central role” in the creation, perpetration and implementation of a racketeering enterprise designed to deceive the public about the dangers of smoking and the addictiveness of nicotine.

“What a sad and disquieting chapter in the history of an honorable and often courageous profession,” Kessler wrote about the role of lawyers.

Her 1,700-plus-page opinion mentioned Shook Hardy and at least a dozen current or former tobacco industry lawyers by name nearly 200 times. It said that for 50 years, the tobacco companies’ lawyers directed the course of scientific research, vetted scientific papers and public relations materials, identified “friendly” scientific witnesses, paid them enormous fees, helped hide their relationship to the industry and took shelter behind baseless assertions of the attorney-client privilege.

While there’s plenty of smoke, there’s been no ethical fire. Even the firm’s harshest critics admit there’s no evidence any of the firm’s lawyers have ever been charged with professional misconduct.

“There’s nothing about our representation of a client that’s been unethical,” says firm chair John Murphy, who makes no apologies for representing clients whose products sometimes kill and injure. Plaintiffs lawyers are “just doing their job, and we’re doing ours.”

MODEST BEGINNINGS

The firm traces its roots back to 1889, when frank Payne Sebree, a Marshall, Mo., lawyer looking to build his practice in a bigger city, moved to Kansas City and set up shop in a third-floor walkup with another solo practitioner. Over the years, the firm attracted a small stable of lawyers, including name partner Edgar Shook, who joined in 1934, and name partner Charles L. Bacon, who came on board in the mid-1950s.

Madelyn Chaber

Photo by Melissa Barnes

However, it was David R. Hardy, a skilled trial lawyer with a larger-than-life personality, who did more to change the firm’s fortunes than anyone.

Hardy made a name for himself in the late 1950s by winning a $200,000 verdict—then a state record—on behalf of a motorcycle cop who had been badly injured in a collision with a cement truck. And when the first anti-smoking suit against a tobacco company in Missouri went to trial in 1962, Hardy was asked by Philip Morris to lead the defense.

Hardy made quick work of the plaintiff, a 62-year-old businessman who claimed he lost his larynx to cancer because of his three-packs-a-day habit. The jury deliberated less than an hour before returning a verdict for the defense.

Philip Morris executives were so impressed with Hardy that they put him in charge of the company’s tobacco litigation nationwide. Five of the industry’s “Big Six” tobacco companies eventually followed suit.

That early tobacco victory also led indirectly to Shook Hardy’s eventual foray into pharmaceutical defense work. Following the verdict, Hardy was asked to speak to a meeting of a national manufacturing group. A lawyer with Eli Lilly and Co. who was present later asked Hardy to recommend a lawyer in St. Louis. Lilly had two cases: One involving an oral contraceptive product and the other the DPT vaccine, a mixture of three vaccines to guard against diphtheria, whooping cough and tetanus. Hardy, who never recommended another lawyer for a job he thought he could do, said he’d do it himself.

Shook Hardy went on to become Lilly’s regional counsel—a new concept at the time—in the oral contraceptive cases and its national counsel in the DPT vaccine cases. Lilly hired the firm as co-national counsel in one of the first pharmaceutical mass tort cases involving diethylstilbestrol, a hormone prescribed for pregnant women at high risk for miscarriage. DES was later found to cause cancer and other diseases in their children.

Other big pharmaceutical companies and medical device makers followed Lilly’s lead. Today, Shook Hardy still represents Lilly and more than 30 other pharmaceutical companies and medical device makers, including Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis, Guidant and Wyeth.

Hardy was the epitome of the well-prepared but down-to-earth trial lawyer, according to John Dods III, who spent 50 years at Shook Hardy. Until his death in early June, Dods served as its unofficial in-house historian.

Hardy spoke in a friendly, folksy manner that juries could relate to. He loved baseball and kept a transistor radio in his shirt pocket so he could keep score of Kansas City Athletics games at work. And he was totally without pretension, Dods said, ordering the blue-plate special for lunch at the four-stool diner down the street from his office.

He was something of a visionary, too. He recognized early on, when most lawyers still thought that all law practice was local, that there was nothing to prevent him from trying cases beyond the borders of Kansas City or Missouri.

Hardy, ironically, didn’t live long enough to see the full fruits of his labors. A longtime Marlboro smoker himself, he died of heart failure at 59 in 1976. A life-size oil portrait of him, holding a pipe, still hangs on one wall of the firm’s mock courtroom, alongside those of the firm’s other name partners.

NO HOLDS BARRED

Product liability defense lawyers—particularly those who represent tobacco companies—aren’t known for being meek. But Shook Hardy lawyers have taken tough tactics to another level, plaintiffs lawyers say. They maintain that the firm is probably in a class by itself when it comes to digging up potential dirt on a plaintiff.

When the daughter of a longtime New Jersey smoker sued several tobacco companies over his death from lung cancer in 1982, the firm’s lawyers reportedly looked into the plaintiff’s two marriages, the guest lists at each of her weddings, the churches her family attended, her childhood friends, even her deceased father’s favorite foods.

That case, which went on for 20 years, was finally settled in 2004 for an undisclosed amount long after the plaintiff’s original lawyers had thrown in the towel, saying they could no longer afford to subsidize the litigation. It was also long after the judge had dismissed most of the claims and three of the four defendants.

In Horowitz’s case, Shook Hardy lawyers even tracked down a cousin in Florida with whom Horowitz used to play poker to ask him if he remembered what brand of cigarette Horowitz was smoking when the two of them got together in Cleveland nearly four decades earlier, according to San Francisco-area lawyer Madelyn Chaber, who represented Horowitz.

Four years after the Horowitz trial, Chaber represented another client in another product liability suit against Philip Morris. Her client was Patricia Henley, a Los Angeles woman who was diagnosed with lung cancer after smoking Marlboros for 35 years.

Henley, then the divorced mother of a 25-year-old woman, hadn’t seen or heard from her ex-husband since he walked out on her and her daughter when the daughter was a young girl. Shortly after the suit was filed, Chaber says, somebody from Shook Hardy managed to locate the man, who was remarried and living in Canada, to inquire if he could ask him a few questions about his ex-wife.

“They’ll do whatever it takes to dig up the least bit of dirt on the plaintiff, no matter how much it costs or who they might offend,” Chaber says. “They’ll investigate every single detail of the plaintiff’s life, from the time they’re born until the time they die, and maybe even further.”

Ray Goldstein, a San Francisco paralegal who has worked opposite Shook Hardy in several anti-smoking suits, says the firm brings in an army of lawyers for every case, deposes everyone they can find, and overwhelms the plaintiff’s side with paperwork.

If you ever lose your dog or you need to locate a missing relative, Goldstein likes to joke, you should just file a product liability suit against a tobacco company and let its lawyers do the work for you. “They’re really good at it,” he says.

Such tactics can sometimes backfire. Henley won a record-setting $51 million verdict, including $50 million in punitive damages, although the judgment was subsequently reduced on appeal to about $17 million, with interest.

Portland, Ore., plaintiffs lawyer Chuck Tauman, who tried a tobacco liability case against Shook Hardy, says the firm tried the same tactic against his client, a former school janitor who died at 67 after 42 years of smoking Marlboros. Firm lawyers went so far as to examine school records in the Texas town where the plaintiff grew up to find out if he had ever attended a health class in which the dangers of smoking were explained.

It didn’t work in that case either. In 1992, the jury awarded the man’s estate $80 million, $79.5 million of it in punitive damages, although the family has yet to see a penny. The case is being reviewed for the third time by the U.S. Supreme Court, which has twice vacated the punitive damages part of the award and ordered the state supreme court to reconsider it.

Judge Kessler isn’t the only jurist to attack the firm as part of the tobacco industry’s defense team. In 1992, U.S. District Judge H. Lee Sarokin of New Jersey issued a stinging opinion in Haines v. Liggett Group, in which he suggested that the tobacco industry had—with the help of its lawyers—engaged in a 50-year conspiracy to conceal the dangers of smoking from the American public. The judge, since retired, was later forced off the case by the industry for alleged bias.

Shook Hardy’s Murphy says he’s not familiar enough with the particulars of the New Jersey judge’s criticism of the firm to comment. And he wouldn’t comment on Kessler’s later opinion except to disagree with it, noting that both sides are appealing the ruling. Kessler found for the government on two counts of racketeering and ordered strict new limits on the marketing and advertising of cigarettes.

MUCH IN DEMAND

The firm’s somewhat mixed trial record hasn’t diminished its appeal to corporate America. Shook Hardy currently is helping coordinate Lockheed Martin’s defense of several hundred silica exposure claims nationwide. It represents the Miller Brewing Co. in several class actions alleging the company’s advertising targeted underage drinkers.

The firm was recently appointed by Pfizer subsidiary Parke-Davis to oversee several hundred cases involving allegations that the anti-seizure drug Neurontin triggered suicide attempts in users. And it serves as national counsel over wholesale price litigation involving prescription drugs for the Paris-based pharmaceutical maker Sanofi-Aventis.

Shook Hardy is Philip Morris’ national counsel in two pending class actions—both medical monitoring claims—in New York and Boston. It is also defending several thousand individual claims in Florida stemming from a 2006 Florida Supreme Court decision to throw out a $145 billion punitive damage award against the industry and decertify a class of 700,000 individual smokers.

Brian Eckman, litigation counsel for Bausch & Lomb, hired Shook Hardy in 2006 as its national coordinating counsel over claims arising from eye infections allegedly caused by one of its contact lens solutions. He says the firm was selected after a search involving about 30 firms.

“They litigate cases as if they’re going to trial, which is not to say they do so unnecessarily. Just that if a matter does end up going to trial, they’ll be in the best possible position to defend it,” he says. “And we like that.”

Best of all, Eckman says, Shook Hardy’s blended hourly rate is a relative bargain, perhaps 10 percent less than many of its big city competitors. Ronald Milstein, senior vice president and general counsel of Lorillard, the country’s oldest and third-biggest tobacco company, agrees. He says he likes “the fact they’re not a big coastal firm. Their rates are better than most big coastal firms. And the quality of the work they do is every bit as good, if not better.”

Laurie Polinsky, former assistant general counsel in charge of U.S. litigation at Sanofi-Aventis, compliments the way Shook Hardy handled a potentially big problem with Ambien, the company’s biggest product and the country’s most widely prescribed sleep aid.

Two years ago the company was hit with a federal class action alleging Sanofi-Aventis had failed to warn consumers about the possible side effects of Ambien, which had been linked to episodes of binge eating and driving while asleep.

In May 2007, a little more than a year after it was filed, the suit was abruptly dropped. Harvey Kaplan, the Shook Hardy partner who chairs the firm’s pharmaceutical and medical device litigation practice, says he and his team talked the plaintiffs’ lawyer out of pursuing the case.

“We convinced her that the chances of class certification were virtually nil,” says Kaplan, who is also a pharmacist and is widely—and affectionately—known in the industry as the godfather of product liability law. “Once she realized we were right, she voluntary withdrew the claim.”

Even Susan Chana Lask of New York City, who filed the case, says it was never about money but about getting the proper warnings out to Ambien users. Once the FDA agreed to mandate such a warning, she says, the issue was settled.

IN-HOUSE EXPERTISE

A big part of the firm’s success, according to Murphy, is its pioneering decision—borrowed from its tobacco industry clients—to create an in-house team of research analysts and paraprofessionals to support its attorneys. That team—which includes more than 100 experts with advanced degrees in biochemistry, neuroscience, electrical engineering, toxicology and other fields—helps create trial exhibits, prepare witnesses, formulate discovery and trial theories, and evaluate complex scientific and technical issues.

“Other firms have tried to emulate our analyst program,” now in its 35th year, Murphy says. “But I don’t think anybody else has duplicated the depth and scope of our program.”

Having that kind of expertise on staff comes in handy, even in a seemingly run-of-the-mill case. Murphy once represented the owner of a drive-in theater that had been sued for negligence by a woman on kidney dialysis treatment who claimed to have ruptured her quadriceps in a slip-and-fall on the premises. A nurse on staff at the firm who reviewed the woman’s medical records knew of a medical link between kidney dialysis patients and a weakening of the quadriceps, which helped nip that claim in the bud.

In addition to its team of in-house experts, many of Shook Hardy’s lawyers also have scientific or technical backgrounds. Partner Madeleine McDonough, who does a lot of pharmaceutical and medical device defense work, was a clinical pharmacist at a university teaching hospital before going to law school. She once put out a firmwide e-mail in connection with a case she was handling involving an alleged E. coli infection. It just so happened that a lawyer in the firm’s Houston office not only had a Ph.D. in microbiology but had written his doctoral thesis on the misdiagnoses of E. coli strains.

The firm has begun growing other practices, particularly its environmental and intellectual property groups, which Murphy says have exploded in the past five or so years. But product liability work remains its core. The practice accounts for three of every four Shook Hardy lawyers and about 70 percent of annual revenues, according to Murphy. About 90 percent of its lawyers are litigators of one sort or another—a remarkably high number for a firm of its size.

With globalization comes the opportunity to introduce more foreign companies to what is, in essence, the world’s largest product liability boutique. As more Asian-made goods are exported to the United States, particularly from China, their makers will undoubtedly face new product liability concerns and have many questions about doing business in America, Murphy says.

“I see a real opportunity to move forward there,” he says.

Source: American Lawyer