Ex-con fights for prisoner rights and battles censorship

Photo Illustration by Monica Burciaga

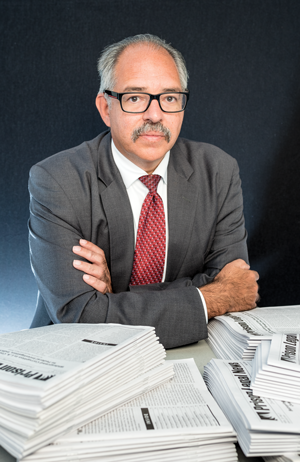

Paul Wright has been fighting to get Prison Legal News into America’s prisons and jails for more than 25 years.

Part journalist, part prisoner-rights advocate, part First Amendment crusader, Wright says his monthly publication doesn’t get a warm welcome from corrections officials whose institutions and practices are often criticized in its pages.

The newsletter, Wright says, “is frequently censored by prison or jail officials around the country who are hostile to an independent media that focus on prison and jail issues.”

Wright’s latest legal battle is in Florida, where the Department of Corrections has been impounding issues for more than a decade based on some of the newsletter’s advertisements, including those for three-way calling services and prison pen pals.

Wright sued the department, arguing that the ban violated freedom of speech and the press as protected by the First and 14th amendments.

“No other prison system or jail in the entire country considers it necessary to censor Prison Legal News on the basis of its advertisements,” according to a PLN brief. “Other prisons face concerns with stamp-based payments or three-way calls and respond to those concerns with sensible regulation of primary conduct, not censorship of critically valuable publications.”

A federal district court ruled in August 2015 that the Florida department’s rule and its application did not violate the First Amendment; however, the court found that there was a due-process problem with how officials confiscated the newsletter. Both sides have appealed to the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Atlanta.

While the battle in Florida continues, Wright and his colleagues have been successful in many other legal battles to get PLN inside prison walls. His organization has even attracted the services of a former U.S. solicitor general.

“One indicator of Prison Legal News’ success is the extent of attempts to ban it by prisons and jails throughout the country,” says Seattle attorney Mickey Gendler, who has represented PLN.

Insider Information

That success was hard-won by a man who’s highly motivated to publicize what he sees as the inequities and indignities of prison life. He should know. He was once on the inside.

Paul Wright spent 17 years in prison after a murder conviction. Photos by Tom Salyer.

Wright was convicted in 1987 for murder in the state of Washington. He was a private in the Army at the time and tried to rob a drug dealer. The dealer attempted to shoot Wright, but Wright shot first and killed the dealer. Wright claimed self-defense but was convicted and sentenced to 25 years in prison. He was released after 17 years in 2003.

While in prison in Monroe, Washington, Wright saw that inmates lacked a constructive outlet to voice their concerns. They had no resources to learn about legal rights, nor ways to advocate for change within the system. He felt that traditional media were either unable or unwilling to report on prisoner rights issues and was compelled to do something himself. “It actually was my frustration with the corporate media ignoring prisoners and our plight on a systemic basis that pushed me to start PLN,” he says.

“Paul was right,” says Peter Y. Sussman, a Berkeley, California-based journalist and author who has written extensively on press access to prisoners. “The press often reflects the public’s lack of interest in knowing anything at all about prison affairs because the public just wants to wash their hands of what happens in prison.”

Sussman says the only way to spark reform is through exposing the system from the inside. “Paul and I share the strong belief that nothing can be done to improve the criminal justice system and the prison system unless the public learns more about what goes on inside these public institutions,” he says.

So in 1990, Wright and fellow inmate and prison activist Ed Mead co-founded the newsletter. “Ed Mead had a history of prisoner-rights activism and publishing when I met him,” Wright says.

The first issue cost $50 to print and distribute—the epitome of a shoestring budget. Wright’s father served as the group’s de facto office manager on the outside.

The first issue featured a variety of articles that included topics such as prisoner-rights court victories, a one-day boycott at the prison in Monroe and a poem by a convicted rapist that was titled The Terror.

Mead has since left the publication, but Wright expanded the newsletter and its reach. Today, Prison Legal News spans more than 70 pages and has a subscription base of more than 10,000. Wright now heads up the Human Rights Defense Center, which began primarily as an organization that published a newsletter on prisoners’ issues out of Lake Worth, Florida.

The Inmates’ Friend

The name Prison Legal News, or its acronym, is instantly recognized among those in the prisoner-rights movement.

“PLN is an indispensable part of the prisoner-rights movement,” says David C. Fathi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project. “PLN has done more for the First Amendment rights of prisoners and their correspondents than anyone else.”

Prison Legal News publishes articles that inform inmates of their constitutional rights, reports on prison abuses, develops articles based on public records requests and chronicles the continuing expansion of mass incarceration.

“We’re proud of most of our content published over the past 26 years, including our extensive reporting on issues like solitary confinement, the Prison Rape Elimination Act and sexual abuse of prisoners,” says managing editor Alex Friedmann, who started writing for the newsletter in 1996 while incarcerated in Tennessee.

Friedmann says the publication has had significant impact with stories that exposed the price gouging of families through the prison phone industry. The stories helped convince the Federal Communications Commission to order rate caps and launch other reforms in 2013 and 2015.

Prison Legal News not only publishes prison-related news but also has a role in litigating prison censorship and public records cases across the country. “Their success rate is close to 100 percent” Fathi says. “They have been described as a litigation juggernaut. If anything, that is an understatement.”

To do all that legal work, PLN has developed a litigation network headed by Human Rights Defense Center General Counsel Lance Weber, who practiced criminal defense in Kansas City, Missouri, for the first decade of his career. “We have established a moderate-sized network of lawyers across the country with whom we have teamed up over the years,” he says.

Lance Weber is general counsel for the HRDC.

Some are high-profile, including former U.S. Solicitor General Paul D. Clement and Michael McGinley of Bancroft in Washington, D.C., who head the PLN appellate team in the Florida case.

Even their adversaries acknowledge the depth and breadth of PLN‘s work. “They know what they are doing,” says Athens, Georgia-based attorney Andrew H. Marshall, who went up against PLN in the state federal court. “It is part of their business to bring suits. They do it quite a bit. They are a well-oiled machine.”

Wright and his team have fought prison and jail officials in more than 30 states that tried to ban Prison Legal News. Many times, a correctional institution will simply confiscate the newsletter and not deliver it to inmate subscribers.

When that happens, the HRDC springs into action. The organization has obtained consent decrees in 10 states that prevent prison officials from failing to deliver the newsletter to inmate subscribers.

In 2010, for example, the HRDC challenged a South Carolina jail’s policy of disallowing inmates any newsletters, magazines or other reading materials. The only reading materials that inmates could receive were paperback Bibles. The U.S. Department of Justice intervened in 2011 on behalf of Prison Legal News. The case was settled in 2012 for $100,000 in damages and nearly $500,000 in attorney fees.

“PLN is the only national organization that I am aware of that has taken on this issue,” explains San Francisco-based attorney Ernest J. Galvan, who has represented the group. “If you look at the major decisions in this area since the mid-1990s, almost all of the important ones have Prison Legal News in the caption.”

Litigating can be costly, but PLN has benefited through some of its victories. Prevailing parties in civil rights cases can recover attorney fees, and PLN and its attorneys have won some large attorney-fee awards. One filed in federal court in Oregon led to an attorney-fee award of more than $800,000.

Wright’s colleagues give him much of the credit for their legal victories, especially because of his unconventional thinking. “Paul is one of the most creative thinkers in our movement,” says Fathi, who’s known Wright for more than 20 years. “He is a master at thinking of new approaches to problems.”

Fathi even has a favorite Paul Wright story. “When Paul was still in prison, prison officials erected an electric fence to prevent prisoner escapes,” Fathi says. “Instead of filing a lawsuit, Paul wrote a letter to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and got the prison in trouble for violating the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.”

While PLN has an impressive litigation record, it’s had some disappointing defeats. In 2012, the 5th Circuit at New Orleans sided with the Texas Department of Criminal Justice after PLN challenged the censorship of several books, including The Perpetual Prison Machine: How America Profits from Crime, in the Texas penal system. The court reasoned in Prison Legal News v. Livingstone that deference and discretion should be given to prison administrators in these subjective assessments of what materials are dangerous.

“Prison and jail officials have found that contraband is smuggled inside correctional institutions through reading materials,” says Virginia Beach, Virginia-based attorney Jeff Wayne Rosen, who is defending a case brought against the Virginia Beach sheriff by PLN. “Courts have upheld many of these policies that restrict the types of materials that inmates can have in prison or jail.”

Sending postcards

PLN also has challenged postcard-only policies in jails across the country. Under these policies, inmates can only receive metered postcards—not even care packages from family members or longer private letters from friends. Officials claim the policies are necessary for security and cost reasons.

“A postcard-only policy helps jails tremendously by decreasing the risk of contraband, crime planning and similar activities,” says Spokane, Washington-based attorney Milton G. Rowland, who has litigated two postcard-only cases against PLN. “If promulgated and enforced correctly, with great care for legitimate interests, a postcard-only policy can be a tremendous benefit to a corrections facility with minimal, if any, impact on the inmate population.”

But Weber argues that postcard policy can deprive detainees of access to important communications. “The majority of the prisoners in county jails are usually pretrial detainees who have not yet been convicted of any crime,” says Weber, who monitors all of PLN’s litigation efforts. “With that in mind, perhaps the most dangerous aspect of postcard-only mail policies is that they tend to completely cut off communication between pretrial detainees and their loved ones outside of the jail.”

PLN successfully has challenged such policies in many counties, including Columbia County in Oregon and Ventura in California. A federal judge explained in Prison Legal News v. Columbia County (2012) that jail officials “have failed to offer evidence or even an intuitive, commonsense reason why the postcard-only mail policy more effectively prevents the introduction of contraband than opening and inspecting letters.”

On the other hand, a federal district court in Georgia ruled in 2014 that there is a “commonsense connection between a jail goal of reducing contraband and limiting the number of pages of correspondence.”

“Challenging these policies is akin to the game Whac-a-Mole,” says Friedmann. “You strike one down and others keep popping up around the country.” The group has pending challenges to postcard-only policies at jails in Michigan, Oklahoma and Tennessee.

Public Records

In its ongoing crusade for prisoners’ rights, the HRDC also advocates for open records within the correctional system. Staff and contributors frequently encounter resistance from prison officials or other government officials when seeking information crucial to their reporting.

“Prisons and jails are the least transparent of all American institutions, including the CIA, the FBI and the NSA,” Wright says. “In the United States, you can learn more about what is going on in a prison in Guatemala than you can learn about what is going in a local jail in the United States.”

The group has sought information detailing how much public money is spent defending prisoner-based litigation each year, and asked for telephone contracts between departments of correction and private companies.

“PLN‘s public records requests frequently get refused or delayed far beyond what would be reasonable, and typically there are no consequences for government officials who refuse to follow the law by honoring the public record requests properly,” Weber says.

In fact, the HRDC, with legal assistance from the American Civil Liberties Union of Vermont, battled for three years with the Corrections Corporation of America over whether records of the private company contracted to run prisons were subject to Vermont’s public records act.

A state judge ruled in 2014 that the CCA was a governmental entity, reasoning that the corporation carries out “uniquely governmental acts” by keeping inmates in captivity, disciplining them, regulating their liberty and carrying out the punishment imposed by judges and juries. The case was settled last November.

“Our position at PLN has long been that when private companies provide essential, fundamental government services, including operating prisons and jails, then their records must be available to the public to the same extent as government agencies,” explains Friedmann.

Trusted and Recognized

The work that Wright and his colleagues have done through Prison Legal News and the Human Rights Defense Center is highly valued among prisoner-rights advocates.

“PLN is a trusted source of information not only for pro se prisoner litigants but also for experienced prisoner-rights attorneys,” says David A. Singleton, executive director of the Ohio Justice & Policy Center, which frequently litigates prisoner-rights cases. “On more than one occasion I have learned of prisoner litigation in another part of the country that has inspired me to bring a similar claim in Ohio.”

The HRDC also has received accolades for its zeal in challenging censorship and pushing for more transparency. In 2013, the HRDC received the First Amendment Award from the Society of Professional Journalists. Wright won the James Madison Award for his efforts to further open government from the Washington Coalition for Open Government in 2007.

Wright is not motivated by awards. “Everything has gotten worse,” he says. “When we began PLN in 1990, there were a million people locked up. Now there are more than 2.5 million locked up. The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world.”

That makes the work even more important, especially when mainstream media seem little interested in covering prison censorship issues. “We are committed to freedom of speech,” Wright says. “We are the only publisher that routinely challenges censorship in the prisons. We are driving this whole area of law.”

“What Paul and Prison Legal News are doing is not only for the benefit of prisoners; it also is for the benefit of society,” journalist Sussman says. “The legacy and great achievement of Paul Wright is that he has linked together the legal aspects, the human aspects, the civil rights aspects, and the information aspects, which affect not just prisoners but the public in general.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Fighting for prisoner rights and battling censorship: An ex-con turns his frustration with corporate media into a ‘litigation juggernaut.’”

David L. Hudson Jr., a regular contributor to the ABA Journal, serves as the ombudsman for the Newseum Institute's First Amendment Center.