Plain talk: A conversation on simplicity with Rudolf Flesch

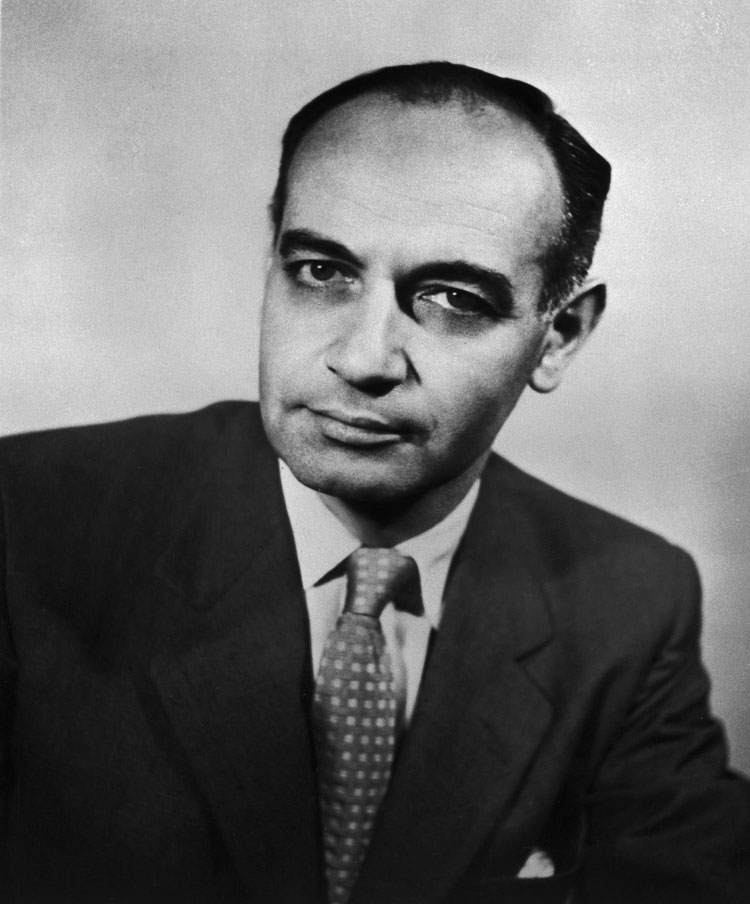

Rudolf Flesch: “What is certain is that legal language is hard even on lawyers.” Photo by Bettmann/Contributor

Garner: You’re especially critical of rules that begin with unless and then stack lots of negatives.

Flesch: Try to read and understand, “Unless you don’t disapprove of saying no, you won’t refuse.” Here it is in Federalese: “Unless the Office of Price Administration or an authorized representative thereof shall, by letter mailed to the applicant within 21 days from the date of filing the application, disapprove the maximum price as reported, such price shall be deemed to have been approved, subject to nonretroactive written disapproval or adjustment at any later time by the Office of Price Administration.”

Garner: That’s certainly opaque.

Flesch: What does that mean for an ordinary person who has reported a ceiling price? Let’s see: Suppose your price is not so high that OPA would disapprove of it. Then OPA would simply not answer, and if 21 days go by without an answer, you would know that your ceiling is all right. All you have to do is send in your application and sit tight for three weeks. So here is what the Federal Register says between the lines: “You must wait three weeks before you can charge the ceiling price you applied for. OPA can always change that price. If they do, they will write you a letter.”

Garner: That’s stunningly simpler.

Flesch: Whenever the government says something in a negative form, turn it around to see what it means. For example: “Sale at wholesale means a sale of corn in less than carload quantity by a person other than one acting in the capacity of a producer or country shipper to (1) any person, other than a feeder; or (2) a feeder in quantities of 30,000 pounds or more.”

Garner: I assume you’ve reworked that regulation without the two other thans.

Flesch: Yes: “A sale at wholesale is a sale of less than a carload of corn by anyone except a producer or country shipper. But a sale of less than 30,000 pounds to a feeder is a sale at retail.”

Garner: Impressive.

Flesch: Underneath the particular features of the nasty, or official, style, there are all the stock elements of bad and unreadable style, and you are back in the familiar game of breaking up worm-sentences, substituting help for facilitate, writing you instead of “the persons named in Appendix 1,” making “upon consideration” into “we have considered,” hunting for whiches that should be thats and so on and so on. The only difference is that officialese is, on the average, worse than any other kind of writing, so that rewriting it in everyday English seems often almost impossible.

Garner: You wonder how lawyers learn to put it into officialese in the first place.

Flesch: They multiply words and use roundabout wordings. When we get down to it, the answer to the question how to read the Federal Register is the same as to the question how to read any other difficult writing: Translate it into your own words, as you would in conversation. That’s a big order, I know, but it’s often the only way to read and understand Uncle Sam’s own prose.

Garner: Can you give us another example?

Flesch: Here’s a complicated legal definition: “Ultimate consumer means a person or group of persons, generally constituting a domestic household, who purchase eggs generally at the individual stores of retailers or purchase and receive deliveries of eggs at the place of abode of the individual or domestic household from producers or retail route sellers and who use such eggs for their consumption as food.”

Garner: Doesn’t seem too bad. How would you translate that?

Flesch: “Ultimate consumers are people who buy eggs to eat them.”

Garner: That’s certainly clearer. It’s so direct that many might fear you’ve lost meaning there.

Flesch: The clauses with the word generally in them don’t belong in a legal definition. And eat is better than use for consumption as food. And let’s just say people instead of a person or group of persons.

Garner: I suppose you’re quite right. In your books, you conceive of language as being essentially democratic.

Flesch: Language is the most democratic institution in the world. Its basis is majority rule; its final authority is the people. If the people decide that they don’t want the subjunctive anymore, out goes the subjunctive; if the people adopt okay as a word, in comes okay. In the realm of language, everybody has the right to vote; and everybody does vote, every day of the year.

Bryan A. Garner, president of LawProse Inc., is the author of Legal Writing in Plain English and more than 20 other law-related books. His most recent is the fourth edition of The Redbook: A Manual on Legal Style (2018). Follow on Twitter @bryanagarner.