North Carolina's Death Row Inmates Let Statistics Back Up Bias Claims

Ken Rose: “[We could] go from being a leader in the area of racial justice to a state that wants to continue to hide from the truth.” Photo by Scott Levoyer

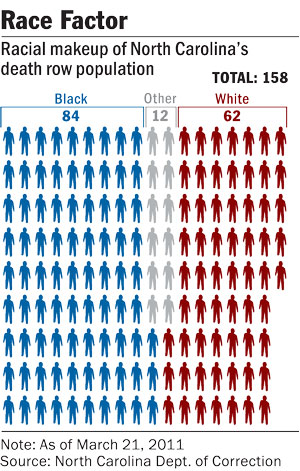

In North Carolina, statistics don’t just tell a story; they can let a death row inmate challenge his conviction. A 2009 state statute allows death row inmates to claim that racial bias unduly influenced the outcome of their trials. The Racial Justice Act specifically allows defendants to use statistics to support their claims. There are more than 150 death row inmates seeking relief under the law.

Errol Duke Moses and Carl Stephen Moseley are two death row inmates seeking to have their cases re-examined under the act. They have been arguing that racial imbalance and bias played a role in both their trials and sentencings.

In February, Forsyth County Superior Court Judge William Z. Wood refused to find that the Racial Justice Act violated the North Carolina Constitution. Wood rejected an argument that the law was too sweeping to apply fairly across the state. Unless reversed on appeal, the judge’s ruling clears the way for other appeals under the law to go forward.

“It will be exciting to watch how the judges rule,” says University of North Carolina law professor Robert P. Mosteller, who recently co-wrote a law review article on the topic. “The first few cases will tell us a good bit about how broadly or how narrowly the courts will apply the statute. No one knows how many people will receive relief under the statute.”

Under the Racial Justice Act, a judge is required to reduce a death sentence to life in prison if it is found that race was a “significant factor” in either seeking or imposing the death penalty. The law allows defendants to appeal using statistics showing racial disparity.

“The statute is hugely important,” says Ken Rose, a senior staff attorney with the Center for Death Penalty Litigation in Durham and an attorney for Moses. “It’s the first of its kind to address in a serious and purposeful way the risk that race is a factor in who lives and who dies in a state’s use of the death penalty.”

SOME BEG TO DIFFER

But opponents say the law is aimed at fixing a problem that doesn’t exist.

“We don’t think that there is a problem of racial bias in the system,” says Peg Dorer, director of the North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys. “What has played out so far has been thousands of hours of prosecutors’ time going back through 20 years of murder cases to try to respond to outrageous discovery demands by defendants, instead of prosecuting the cases that the citizens need prosecuted. This is not a good use of taxpayer money or state employee time.”

Legal scholars following the issue expect that a number of courts in the state will be grappling with how best to apply the statistics in individual death penalty appeals.

Death row inmates challenging their sentences under the law have been relying in large part on two Michigan State University College of Law studies examining racial bias in North Carolina cases. According to one of the studies, 31 death row inmates in the state had all-white juries and 38 had only one person of color on the jury.

One study found that between 1990 and 2009, in more than 1,500 cases, North Carolina defendants of all races were more than twice as likely to receive the death penalty if one or more of their alleged victims was white.

The second study found that in North Carolina’s death penalty cases, prosecutors removed prospective black jurors from jury panels at more than twice the rate that they removed prospective jurors who weren’t black. Under the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1986 case Batson v. Kentucky, a prosecutor may not use peremptory challenges to exclude jurors based on their race.

Other states are also reviewing their death penalty laws. Maryland has suspended the death penalty pending review of lethal injection. In recent years, three states—Illinois, New Jersey and New Mexico—have abolished the death penalty altogether.

Graphic by Adam Weiskind

LONG THREAD OF DEBATE

The issue of racial disparity in capital cases has been debated for decades. In 1987 the Supreme Court said in McCleskey v. Kemp that a statistical study alone was not adequate evidence of racial bias to overturn a death penalty conviction. However, supporters of the North Carolina law say the Supreme Court ruling left open the door for federal and state legislatures to create remedies for addressing racial discrimination in capital cases.

In 1988 death penalty foes applauded Congress’ attempt to pass a federal racial justice act, but the bill was eventually defeated. Subsequent versions of the act were later introduced and defeated in Congress. The American Bar Association has stated its concerns with the application of the capital punishment system in the U.S.

“If you are going to have a death penalty, you should get the death penalty because of the nature of the crimes or crime you have committed in light of your background, not based on your race or the victim’s race or both,” says Ronald J. Tabak, co-chair of the Death Penalty Committee of the ABA’s Section of Individual Rights and Responsibilities and special counsel for pro bono and general litigation in the New York City office of Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom.

“To the extent that valid studies show patterns of racial disparity that cannot be explained by nonracial factors, that is something that the ABA views as unacceptable.”

Kentucky was the first state to pass a racial justice act. But North Carolina’s law appears to have “more teeth,” according to Harvard criminal law professor Carol Steiker, who specializes in death penalty issues.

The Kentucky law allows statistical evidence to be used but requires that this evidence be linked to the defendant’s specific case, Steiker says. The North Carolina statute allows the use of statistics to show a pattern of discrimination in a broad number of cases drawn from the county, prosecutorial district, judicial division or the state at the time the death penalty was sought or imposed.

“North Carolina’s statute is the first one involving capital cases that allows an inference of discrimination to be drawn based on statistics. It is a watershed moment,” Steiker says. “There’s no question that this statute is a new and different animal from anything that has come before.”

Once a defendant has proven that race appears to influence outcomes, the burden then shifts to the prosecution to show that there is a race-neutral explanation.

“Now we wait to see what the defendants can bring by way of statistical evidence and what efforts the state will make to rebut,” says Steiker. “There are clearly a lot of people sentenced to death in North Carolina who believe they can establish a case.”

Death penalty foes and advocates are tracking the appeals in North Carolina for insight into how other states would fare with similar laws. Pennsylvania, for example, has been considering a bill similar to North Carolina’s law.

But the Racial Justice Act may well be headed toward extinction. Republicans in the state legislature have been discussing either severely narrowing or entirely repealing the controversial law.

Dorer says the North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys supports legislative efforts to amend or repeal the law. Dorer argues that there are numerous opportunities during a trial and afterward to pursue an argument that the proceeding is being tainted by racial bias.

“The Racial Justice Act, while it has a very good title and a very good intent, basically says that the way you prove bias is with statistics,” Dorer says. “District attorneys feel like every case, and especially a death penalty case, should be judged on its merits and the actions of the defendant.”

But supporters like Rose say that repealing the statute would be a “huge setback.”

“We would go from being a leader in the area of racial justice to a state that wants to continue to hide from the truth,” Rose says.