Meet the father of the landmark lawsuit that secured basic rights for immigrant minors

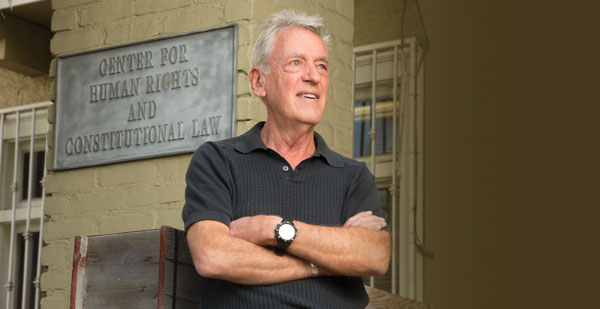

Carlos Holguín. Photo Illustration by Brenan Sharp and Tony Avelar

That wasn’t unusual. Holguín represented such people often as an attorney at the Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law, a public interest firm in Los Angeles. And it was 1984, a time when migrants from El Salvador, like this 15-year-old girl, were coming to the U.S. in droves to escape their country’s brutal civil war.

What was unusual was the caller’s concern: The Immigration and Naturalization Service (a precursor to today’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement) wouldn’t release the girl to anyone but a parent or guardian, a policy created for children’s safety. The problem was that parents without legal status, like the girl’s mother, would be arrested and deported if they came for their children. Civil rights attorneys were starting to believe the policy’s real purpose was to use the kids as bait.

Holguín wasn’t sure it was a good idea to challenge a policy intended to protect minors. But then he saw where they were being kept. In the Hollywood neighborhood of Los Angeles, authorities had taken over a 1950s-style motel. Though it was surrounded by single-family homes, the motel had been an eyesore and was frequented by prostitutes and drug users. The INS contractor Behavioral Systems Southwest had drained the swimming pool, covered the front of the property with chain-link fence and strung up concertina wire.

“Visually, it was the worst facility I’ve ever seen,” says Holguín, still general counsel at the center. “It was an extremely makeshift situation for a facility, especially to be holding children.”

It wasn’t much better inside. The detainees had no right to visitation, no recreation, no education for the minors and little to do. Unaccom-panied minors were often informally adopted by older women who shared their rooms, Holguín says. But during the day, kids mixed freely with adults of both sexes, with no evident concern about safety.

“That treatment and those conditions were completely inconsistent with any real concern for their welfare,” says Holguín. “It certainly persuaded me, and I think it ultimately persuaded the court, that the ostensible concern that the agency had for the well-being of the minors was not sincere.”

“It was horrifying, coming from the child welfare and even the juvenile justice world, to see how these kids were treated,” recalls Alice Bussiere, who eventually became Holguín’s co-counsel on the matter. Then an attorney at the National Center for Youth Law, she works today for the Youth Law Center in San Francisco.

Children also were subject to arbitrary strip searches. John Hagar, who was then an attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, recalls that staff at one big INS facility would bring minors into the gym every morning, erect a screen between boys and girls, and search everyone. Hagar, now a solo attorney in Sacramento, says authorities never found anything in body cavities, though they found broken mirrors on two girls.

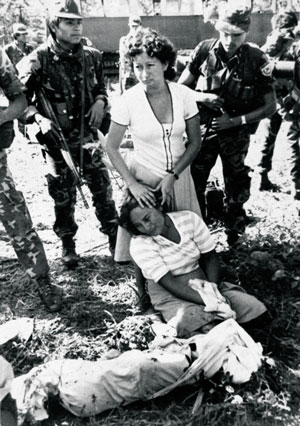

A woman grieves for her son killed in a guerrilla attack in El Salvador, 1984. Photograph by AP Photo/Luis Romero.

In an effort to keep children from living in such conditions, Holguín and his co-counsel sued—and changed the legal landscape surrounding the rights of immigrant minors. The 1985 class action lawsuit they filed to strike down the parents-only release policy became Flores v. Meese (for Edwin Meese, the U.S. attorney general at the time, and lead plaintiff Jenny Lisette Flores, a 15-year-old detainee). The suit ended in a settlement that’s still among the most powerful legal tools available to immigrant children’s advocates.

“The Flores case overall is a crucial landmark case in U.S. immigration history and, frankly, in the treatment of children under U.S. law generally,” says Denise Gilman, director of the University of Texas School of Law’s Immigration Clinic and current vice-chair of the Committee on Rights of Immigrants in the ABA Section of Civil Rights and Social Justice.

“The difference today, where the [federal government] is putting people in foster care and looking at other avenues to house these kids, as opposed to putting them in detention centers, is really remarkable,” says Steve Schulman, leader of the pro bono practice at Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld in Washington, D.C., and another former co-counsel.

The Flores settlement has been invoked in at least four enforcement actions and numerous individual petitions, and it continues to make a difference today. Last year, the settlement formed the basis for a strongly worded federal court order stopping Immigration and Customs Enforcement from detaining all immigrant mothers with children. Now styled Flores v. Lynch—the case has outlasted eight attorneys general—it’s currently pending before the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at San Francisco.

Throughout the case’s convoluted history—which includes a trip to the U.S. Supreme Court and yearslong settlement negotiations—Holguín has been its lead counsel and shepherd.

“No question that he is the driving force behind this litigation for a long, long time,” says Peter Schey, who—as president and executive director of the Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law—has been Holguín’s boss for more than 30 years. “We wouldn’t be where we are today without his creative development of strategies and legal brief-writing.”

Carlos Holguín. Photograph by Shutterstock.com.

UNWELCOME MESSAGE

The Flores case garnered widespread media attention because of the 2014 surge of Central Americans seeking refuge from rampant gang violence in their home countries. Much of the publicity focused on unaccompanied minors, whose numbers had been increasing dramatically over the past few years. Federal authorities, trying to keep up, established temporary shelters and “rocket dockets” in immigration court for the minors.

However, the media paid less attention to the increase in apprehensions of mothers with small children in tow. Immigrant adults, even those with children, have fewer legal protections than unaccompanied minors—whose treatment by authorities is prescribed by the Flores settlement and federal law.

As a result, the federal government could quietly adopt a policy of detaining all immigrant women with children, which was expressly intended to deter would-be migrants. Upon the opening of the South Texas Family Residential Center in Dilley, Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson told a press conference: “Frankly, we want to send a message that our border is not open to illegal migration; and if you come here, you should not expect to simply be released.”

Immigrant advocates picked up on that message, and they were not pleased. Holguín, who as Flores class counsel has a limited right to enter detention facilities, went to visit the Artesia, New Mexico, temporary family detention center. (The center was closed in fall 2014 to shift inmates to more permanent facilities.)

There he was surprised and disturbed to see “very, very young children”—nursing babies to maybe 6 years old—in secure lockdown facilities. He was used to seeing minors in prisonlike conditions, but they’d typically been 12 to 17. It was disconcerting to see so many babies, he says, particularly since there were complaints about poor medical care.

Holguín came away saddened at first—and then motivated by anger to do something about it. It’s a progression he’s felt over and over throughout his career.

“There’s just no way to describe what it’s like to sit across the table from [people] like the women who are being held in Texas, and not come away with an intense emotional experience,” he says. “I’m not one to wear my emotions on my sleeve, but I’m not going to deny that I’ve been very moved by a lot of the suffering of the people I’ve dealt with and defended over the years.”

Holguín’s closest colleagues say this kind of quiet passion is not unusual for him—especially on issues affecting immigrant kids. “He seems to be very motivated by correcting injustices, particularly, in my experience, those that affect children,” says Bussiere of the Youth Law Center, one of the few Flores co-counsel who has stayed involved throughout the case’s history.

“He’s clearly motivated by his strong commitment to social justice,” says Schey, “and much of that time has been dedicated to the plight of immigrant children.”

He’s also a very practical lawyer, Bussiere says. “I think he starts with ‘What is the problem we’re trying to solve?’ and moves to ‘What is the legal mechanism for solving that problem?’ ” she says. “In other words, he’s not always immediately going to litigation.”

Photograph by Tony Avelar

Holguín himself illustrates that with a story about California’s Proposition 187, a 1994 ballot initiative intended to deny eligibility for most state services to immigrants in the country without papers. Holguín and Schey were counsel in one of the four lawsuits—which were consolidated before the 9th Circuit—challenging the measure. The state had been fighting those cases until 1999, when Gov. Gray Davis was elected and pushed for a settlement.

Holguín and Schey were particularly concerned about minors being denied the right to go to public schools, in part because they’d worked on Plyler v. Doe, a 1982 case in which the Supreme Court said children without papers may attend public schools. Holguín says one of the other attorneys on the case resisted settling, arguing that they should keep appealing so the court would revisit Plyler. But Holguín felt he had an obligation to his clients.

“I said no, we’re not going to place the education of thousands of kids at risk,” Holguín says. “I’d just as soon get the win. If kids go to school, move on to something else.”

In the end, he says, he was “tickled pink” when the state settled the matter with mediation. What remained of Proposition 187 was later repealed.

JUSTICE YOU SHALL PURSUE

Holguín says activism is a family business. His grandfather, who left Mexico during the country’s 1910-1920 revolution, was a union organizer who “used to make speeches to the organizing workers in the plazita” in Los Angeles. His father, a teacher in the heavily Latino public schools of East Los Angeles, was involved in the Los Angeles Unified School District’s 1968 student walkouts protesting open racism and substandard education for Mexican-Americans. The district asked the elder Holguín to organize the parents into advisory councils intended to mollify them; instead, he encouraged sit-ins and confrontations with administrators.

The Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law in Los Angeles. Photograph by Tony Avelar.

The focus on social justice has carried on to Holguín’s own children. His son, a recent law graduate, had volunteered with the ACLU, the Inner City Law Center and other public interest organizations throughout law school. His daughter, a baby in his desktop photo, was working on a master’s degree in social work last fall. After graduation, she planned to work for the Los Angeles County child welfare agency, just like Holguín’s wife.

Though Holguín is from the second generation of his family born in the United States, he believes his heritage plays a part in his focus on immigration. He has plenty of relatives in Mexico and even recalls an uncle from Chihuahua, who had no papers, living with his family when he was young. “The differences between us, when you’ve got family ties and so forth, are not that great,” he says. “And when you see people who are ‘but for the grace of God, there go I,’ it definitely is key to the things that one thinks are important.”

In his spare time, Holguín is still focused on social justice. For years, he’s played with a band performing nueva canción—the Latin American genre of politically aware folk music. (One of its most famous artists was the Chilean Víctor Jara, who wrote his last poem just before his torture and execution by Augusto Pinochet’s forces.) Over the years, he says, they’ve played at events for unions and other causes.

He has a vacation house in Mexico, and even when he goes there for time off, he’s working to help migrants. His house happens to be near a rail line that carries Central American migrants north. Sympathetic locals regularly wait for trains, then drive alongside and throw bags of food to the migrants huddled on top. Holguín took a trip in November that included meeting up with those migrants, as well as taking a trip to migrant camps in the state of San Luis Potosí.

“It’s killing two birds with one stone,” he says. “There’s the musicians I play with down there. I’ve got artist friends, but everyone’s kind of mixed up in trying to do something, particularly recently with respect to the Central American migrants.”

LAW AS ENTRÉE TO POWER

As a young adult in the late 1970s, Holguín decided law school was the best way to pursue justice. “It seemed to me, and I think this has proven to be a correct assumption, that the courts and the law offer us an entrée point to political power that is very difficult to get through other means,” he says. “It always struck me that as long as the U.S. judicial system is inclined to intervene on behalf of disadvantaged people, that we ought to be taking advantage of that opportunity.”

The law school he chose was not one of the prestigious programs at LA’s major universities, but the People’s College of Law, a school founded to train lawyers—particularly lawyers of color—“dedicated to securing progressive social change and justice.”

In the late 1970s, Holguín says, the school attracted students who turned down Harvard. And it provided experiences he “wouldn’t change for anything,” he says, including courses taught by working civil rights lawyers. One, Ben Margolis, had famously defended blacklisted entertainment writers and directors who refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1947.

“There was an environment of ‘We’re here to learn how to have social impact and political impact through the practice of law,’ ” Holguín says.

While he was still in law school, Holguín started working at the National Center for Immigrants’ Rights (today called the National Immigration Law Center), a backup facility for legal aid workers dealing with immigration law. It was housed at the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles. After passing the bar in 1979, he worked there full time under Schey.

The first case Holguín felt was his own was Orantes-Hernandez v. Meese, a class action on behalf of Salvadoran nationals alleging mistreatment by U.S. immigration authorities. The Border Patrol was used to getting Mexican nationals to sign voluntary departure forms, he says—but for Salvadorans, going home could be fatal.

“The Salvadorans were refusing to sign the voluntary departure forms, and the Border Patrol just didn’t know what to do,” he says. “So they started in all sorts of shenanigans. They lied to them, they would choke them, they would deprive them of food.”

SLOW START

It was an uphill struggle, Holguín says—a major, fact-intensive class action case. He’d only been admitted to practice law for about a year at that point, but he was lead counsel.

Looking for more information on the allegations of abuse, Holguín drove down to El Centro, a small city east of San Diego and near the border, where the INS had a detention facility. His employer couldn’t afford a motel, so he slept in his van outside the facility.

Peter Schey. Photograph by Tony Avelar.

There, he got the names of a few detainees, then filed entries of appearance as their attorney and interviewed them. Each time he spoke to someone, he asked for the names of other detainees willing to tell him about abuses.

Then, he says, it snowballed to 50 or 60 declarations. One migrant told him INS agents ambushed him in the street, beat him and shoved him in a van during his arrest. Another, a woman, said INS officials implied that if she didn’t sign a voluntary departure form, they’d permit male detainees to rape her. Migrants said INS agents routinely told them they would be imprisoned for a long time if they refused to sign, that signing was mandatory, and that they would be deported no matter what.

Back in LA, Holguín went to federal court to ask for an injunction against abuses. After making his argument, he was surprised to see the government’s attorney addressing the judge in a way that seemed overly familiar. His co-counsel, a pro bono attorney from Munger, Tolles & Olson, told him the government’s attorney played golf with the judge. Holguín saw it as a transparent attempt by the INS to win by networking instead of on the merits—but ultimately, the judge sided with him, giving him his first major victory.

In 1988, Orantes-Hernandez led to a permanent injunction from the Central California district court, forbidding the INS from using threats, intimidation and misrepresentations to pressure Salvadorans into signing the forms.

But by then, Holguín was off the case. In 1982 and 1983, when the Legal Services Corp. became politicized, Congress forbade LSC-funded organizations from pursuing class actions or representing immigrants present illegally. That was essentially all Holguín and Schey did, so they left.

Schey founded the Center for Human Rights and Constitutional Law, but Holguín didn’t immediately follow. Rather, he spent 1983-1984 at Westside Legal Services, a legal aid center that closed in 1994. There, he discovered that he was burning out from too many 70-hour workweeks. Looking for a position where he could work more reasonable hours—but still make a difference—he rejoined Schey at the center.

THE CALL THAT CHANGED IT ALL

Shortly after he started at the center, Holguín got the call from the Hollywood actor (whom he declines to name for attorney-client privilege reasons)—and launched into what became the Flores case that, more than 30 years later, is still one of the most important of his career.

Holguín started out by visiting immigration detention facilities to talk to the minors about the parents-only release policy. After seeing the Hollywood facility and others, he grew concerned about the conditions of their detention as well. He enlisted Bussiere, Hagar and others for their expertise in youth law.

Bussiere says their original strategy illustrates Holguín’s practical approach to problem-solving. The goal was to get the kids out, not file headline-grabbing impact litigation—so they started by trying to get a court to appoint nonparents as guardians. Immigration judges sent them to federal court, which Holguín says eventually appointed guardians, despite a lack of clear authority to do so.

But, looking for a broader solution, Holguín and his co-counsel filed a class action lawsuit, seeking to end both the parents-only rule and the poor conditions in the facilities. Holguín says he can no longer remember why Flores was chosen as lead plaintiff. But her story is not unusual: She came to the United States at the age of 15, intending to reunite with her mother in Los Angeles. But because her mother wasn’t there legally, she was stuck in INS detention in Pasadena.

The case had some early victories: The court certified a class, then struck down the strip-search policy. Not long afterward, the federal government entered into a partial settlement—a memorandum of understanding covering the con-ditions of detention.

But the real fight was about detaining the minors in the first place. Holguín’s team wanted kids to be released to any responsible adult who would claim them, provided he or she had received the kind of vetting a child welfare agency would use. The INS had never done that and claimed it couldn’t afford to.

It was a lengthy fight. The plaintiffs eventually won at the district court on due process grounds, but the case was reversed at every stage: a 9th Circuit panel found for the government, the en banc 9th Circuit found for the plaintiffs, and the U.S. Supreme Court found for the government.

Holguín argued the case before the Supreme Court—his first argument, though he’d been there three times before with Schey. “It was a remarkable experience,” he says. “It’s an honor to be able to go to the court and argue, and you’ve got the history that’s there. In some way, you’re in the shadow of Justice Marshall when he was working for the NAACP.”

But from a practical standpoint, a trip to the court was bad news for his clients. “I felt that the only way to go after the 9th Circuit’s en banc decision was down, which is exactly what happened,” he says. “I think as a lawyer, your first duty is to your clients; and if your clients have won, you don’t want that win exposed and jeopardized by taking it to the Supreme Court.”

‘GOOD ENOUGH’

That apprehension was borne out by the 1993 Supreme Court decision, which was a defeat on the law. Writing for the seven-justice majority, Justice Antonin Scalia framed the issue as the right to be released to a nonparent adult—then said there was no such right. He also found no requirement in the Constitution for a hearing on alternative placement “so long as institutional custody is (as we readily find it to be, assuming compliance with the requirements of the consent decree) good enough,” he wrote.

Holguín wasn’t surprised. From the questions asked at oral argu-ment, he’d figured Justice John Paul Stevens was on his side, but he wouldn’t be able to enlist enough support to form a majority. (Indeed, Stevens dissented, joined by Justice Harry Blackmun.)

“The real question was: ‘Would the court leave enough for us to be able to salvage something?’ ” Holguín says.

It did. Over the next four years, Holguín and his co-counsel persisted, negotiating a settlement that Bussiere says “achieved all our goals.” Holguín says public pressure on the INS—which had “taken a beating in the press”—was a major factor, along with the Supreme Court’s “good-enough language.”

“When it was remanded, we began to marshal evidence showing that conditions weren’t quote-unquote good enough,” he says. “They continued to violate even the memorandum of understanding to keep kids in substandard conditions.”

The result was the 1997 Flores settlement. Today, it’s one of the key legal protections for unaccompanied immigrant minors who are detained by the federal government. The settlement requires minors to be released promptly or, if that’s not possible, placed in the least restrictive setting appropriate for their situations. It lays out the right to basics like adequate food, water, sinks, toilets and medical care. Holguín says it was the basis for a provision in the 2002 Homeland Security Act that took detained minors out of INS custody.

And it’s been a powerful tool for immigrant children’s advocates. During the most recent wave of immigration, students at the University of Texas immigration law clinic regularly invoked Flores when arguing for releasing mothers with children, says the clinic’s Gilman. During a prior wave, it was the basis for civil rights lawsuits against a now-closed family detention facility in Texas.

Flores itself has been reopened at least three times—in 2001, 2004 and 2014—because of alleged violations of the settlement’s guarantee of safe conditions and prompt release. The most current reopening ended with an order giving the federal government until October to release minors and their mothers from immigration jails. The government has done so, but advocates are still concerned about conditions for those who remain.

PROUD COMPARISON

Though three decades of litigation haven’t eradicated bad conditions for detained immigrant minors, Holguín says he’s proud of what he’s been able to accomplish, in the face of “very, very macro political forces” that have stymied current immigration reform efforts, even under a Democratic president.

“The power of argument, which is all we lawyers have—it’s just a weak tool given these global forces,” he says. “So when I stop and think about what our office has accomplished in that context, then I’m quite proud.”

The changes they’ve won have permitted thousands of kids every year to be released from custody, improving their chances of winning asylum. Holguín has met just a few of them—that’s the nature of “impact litigation,” he says. Even Flores and her co-plaintiffs fell out of touch in the 1990s. But he knows he’s made a difference.

“I know people who are sort of new to this, and they go into the facilities and they say, ‘This is horrendous,’ ” Holguín says. “And they’re right. But the truth of the matter is that if they would have gone in and seen how these kids were being treated in 1985 and 1986, you would see it’s like night and day, how much better things are.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “The Passionate Pragmatist: Meet the father of the landmark lawsuit that secured basic rights for immigrant minors.”