Logjam

Photo by Kristine Strom

In 1994, Judge J. Dickson Phillips Jr. of the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals took senior status—a form of semi-retirement available to judges who turn 65 and have completed at least 15 years of service.

So far, no one has been able to take his place, literally. The seat held by Phillips, a 1978 appointee of President Carter, is the longest-running vacancy in the federal appellate system.

President Clinton tried twice to fill Phillips’ seat and was foiled both times by Sen. Jesse Helms, R-N.C. Helms was reportedly miffed at Senate Democrats for having previously failed to confirm Terrence Boyle, a federal judge and former Helms legislative aide, who had been nominated for a different opening on the Richmond, Va.-based circuit.

Shortly after President George W. Bush took office, Boyle was once again nominated—reportedly at Helms’ urging—this time for Phillips’ seat. But another North Carolina senator, Democrat John Edwards, blocked the appointment—doing unto Boyle what Helms had done to the Clinton nominees.

Last year, Boyle took himself out of contention. Six months later, Bush nominated Chief Judge Robert J. Conrad Jr. of the Western District of North Carolina for the slot. Conrad is opposed by liberals for his views on abortion, religion and the death penalty, leading some to believe that Democrats plan to hold the seat open until they see whether it can be filled by a Democratic president.

Phillips, now living in Chapel Hill, N.C., seems resigned to the political aspects of the judicial selection process but is none too eager to discuss it. “I’m 85 years old and I’m sitting here calmly,” he says. “I’d rather not get into it.”

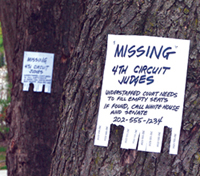

The 4th Circuit is the most shorthanded of any federal appeals court, by a wide margin. As of early May, five of its 15 seats were empty, accounting for more than one-third of the 13 circuit court openings nationwide. Only five other circuits have empty chairs—and no other circuit has more than two.

Three of the 4th Circuit’s openings are considered “emergency” vacancies—a designation based on circuit panel caseload, as well as duration of the vacancy.

At deadline, Senate leaders had reached a tentative agreement to confirm G. Steven Agee, a justice on the Virginia Supreme Court who was nominated in mid-March. Should the full Senate vote to confirm Agee, he would be the first judge to join the 4th Circuit since 2003.

POLITICAL SPLIT

The reason the nomination logjam has lasted this long is that judicial retirements have turned what was once the nation’s most reliably conservative appellate court into one split evenly—between judges appointed by Democratic presidents and those appointed by Republicans.

With the circuit’s ideological direction hanging in the balance, there’s been near-paralysis in Washington. The president has nominated reliably conservative lawyers to fill most of the vacancies, and the Democrat-controlled Senate has failed to act on most of the nominations. Meanwhile, the work of the circuit grinds on, with fewer and fewer judges to shoulder the burden.

Since Democratic Party leaders are feeling confident about their prospects for retaking the White House this fall, chances that any nominees beyond Agee will be confirmed before Bush leaves office in January range from slim to none, most experts say. And if the next president is a Democrat, his or her nominees could remake the 4th Circuit into a more moderate appeals court for a generation or more.

“I think the president has missed whatever opportunity he may have had to leave his mark on the 4th Circuit, which is really kind of ironic,” says University of Richmond law professor Carl Tobias, who studies the federal judicial selection process in the city where the circuit is based. Bush “basically did everything he could to make the court even more conservative than it was—and it’s actually become less conservative over the course of his administration.”

The 4th Circuit, which hears appeals from the federal trial courts in five mid-Atlantic states from Maryland to the Carolinas, is neither the biggest nor the busiest of the 12 geographically organized circuits. But it is arguably one of the most influential.

Through much of the 1990s, the circuit became an ideological testing ground for cases advancing a conservative agenda, observers say. In key cases, the court sided with those advocating for a strong executive branch and the rights of corporations.

The 4th Circuit essentially gutted the citizen-suit provision of the Clean Water Act in Friends of the Earth v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, 149 F.3d 303 (1998); found the civil rights remedy of the Violence Against Women Act unconstitutional in Brzonkala v. Virginia Polytechnic Institute, 169 F.3d 820 (1999); upheld a challenge to the Miranda rule in United States v. Dickerson, 166 F.3d 667 (1999); and blocked an attempt to regulate nicotine by the Food and Drug Administration in Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp. v. Food and Drug Administration, 153 F.3d 155 (1998).

Since 9/11, the circuit has been at the forefront of the government’s legal war on terrorism. That’s partly a matter of geography. The circuit includes the Eastern District of Virginia, where the Pentagon and CIA headquarters lie, just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. It is also home to military bases where three enemy combatants who are American citizens have been held.

But experience also plays a part. In a 2002 interview with the ABA Journal, Paul McNulty—then the U.S. attorney in Alexandria, Va.—said terrorism cases are often filed there because of the jurisdiction’s prosecution-friendly juries and judges familiar with the handling of classified information in spy trials.That’s why 9/11 conspirator Zacarias Moussaoui—who could have been tried in Minnesota, where he was arrested, or Manhattan, where most of the 9/11 fatalities occurred—stood trial in Alexandria. That also explains why the military plane carrying “American Taliban” John Walker Lindh landed at Washington Dulles International Airport in the Virginia suburbs, rather than San Francisco International Airport, where his journey to the war began.

FED-FRIENDLY

Like the Eastern District of Virginia, the 4th Circuit has been largely supportive of the government’s positions in terrorism cases. It denied the right of a U.S. citizen captured overseas and held without charge to use the courts to challenge his detention as an enemy combatant in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 316 F.3d 450 (2003); upheld the indefinite detention of an American citizen captured in the United States as an enemy combatant in Padilla v. Hanft, 423 F.3d 386 (2005); and refused to reinstate a lawsuit by a German citizen who claimed he had been tortured by the CIA in an Afghanistan prison after mistakenly being identified as a terrorist in El-Masri v. United States, 479 F.3d 296 (2007).

The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear appeals by Jose Padilla, 126 S. Ct. 1649 (2006), and Khaled El-Masri, 128 S. Ct. 373 (2007). But it reversed the 4th Circuit in Hamdi, ruling 6-3 that an American citizen has a due process right to contest the factual basis for his classification as an enemy combatant. 542 U.S. 507 (2004).

ENDLESS DEBATES

That so many of the 4th circuit’s judgeships remain vacant is not for lack of trying. The circuit’s fractious history says much about the politicized—and increasingly polarized—judicial selection process of the past two decades.

The constant bickering “causes delays, creates hardships, frustrates the goal of appellate justice and undermines public respect for all three branches of government,” Tobias says.

The second-oldest vacancy on the 4th Circuit was created in 2000, with the death of Judge Francis D. Murnaghan Jr., a 1979 Carter appointee.

Early in Bush’s first term, the administration had floated the name of Peter Keisler, a prominent D.C. lawyer who lived in Bethesda, Md., as a possible nominee. But Keisler, who was not a member of the Maryland bar, took himself out of the running when Maryland’s two Democratic senators made it known they wanted a nominee with deeper ties to the state. (Keisler has since been nominated for the District of Columbia Circuit to the seat vacated by John G. Roberts Jr. when he left to become chief justice of the United States.)

In his place, the president nominated another former Helms aide, Claude Allen, who served as Bush’s chief domestic policy adviser. The nomination of Allen, a Virginia lawyer with few apparent ties to Maryland, went nowhere. And Allen, who eventually withdrew his nomination, later resigned from the administration after being arrested in a bizarre scheme to defraud retailers by returning goods he never purchased. He subsequently was fined and placed on probation after pleading guilty to a single count of shoplifting.

Bush has since nominated Maryland U.S. Attorney Rod Rosenstein for Murnaghan’s seat. But Rosenstein’s nomination may also be in trouble because the state’s two Democratic senators say they want him to remain the state’s top prosecutor. They also say his roots in the state aren’t deep enough to merit appointment for a seat representing Maryland on the 4th Circuit.

The 4th Circuit’s third pending vacancy stems from the sudden resignation in 2006 of J. Michael Luttig, a 1991 appointee of President George H.W. Bush, to take a position as general counsel and senior vice president of the Chicago-based Boeing Co.

At the time of his resignation, Luttig, one of the court’s resident intellectuals and a frequently mentioned candidate for an opening on the Supreme Court, attributed his decision to leave to the “sheer serendipity” of having been approached about the Boeing job only a few weeks earlier. But Luttig also clashed with the administration over its handling of the terrorism case against alleged “dirty bomber” Padilla and was said to be deeply disappointed at having been passed over for the Supreme Court vacancies that went to Roberts and Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. Luttig declined to comment for this story.

If the Senate confirms Agee—whom Bush nominated nearly two years after the vacancy was created—he would take Luttig’s place.

The appeals court’s fourth vacancy was created last July, when Chief Judge William W. Wilkins, a 1986 appointee of President Reagan, took senior status. Two months later, Bush nominated Columbia, S.C., lawyer Steve A. Matthews.

But Matthews, whose nomination is still pending, has also come under fire from some liberals for his conservative background and his limited courtroom experience.

The 4th Circuit’s most recent opening has been in the works since 2001, when H. Emory Widener Jr., a 1972 appointee of President Nixon, announced his intention to take senior status as soon as a successor was confirmed.

In 2003, Bush nominated William Haynes II, then-general counsel of the Defense Department. But Haynes’ nomination drew opposition from Democrats and some Republicans for his role in the drafting of controversial interrogation techniques and detention policies for suspected terrorists.

When Haynes withdrew early last year, Bush chose Richmond lawyer E. Duncan Getchell Jr. to succeed Widener. But Getchell—whose name had not been on a bipartisan list of five candidates recommended by the state’s two senators—pulled out of the race in January, citing the “unfavorable” political climate.

Widener, in the meantime, had given up waiting for a successor. He took senior status in July last year but died a few months later, his seat still unfilled.

SMALL BUT SPEEDY

Despite the judicial shortage, the 4th circuit continues to dispose of cases quicker than almost any other circuit. But it does so while granting oral argument in fewer cases than its counterparts, and by issuing fewer substantive opinions explaining its decisions.

In 2006, the 4th had an average disposition time per appeal of 91⁄2 months, which tied the 11th Circuit as the quickest in the nation. The 9th Circuit had the slowest, at nearly 16 months. The national average was slightly longer than 12 months.

Judges in the 4th Circuit also consistently rank as among the hardest-working in the federal appeals courts. In fiscal year 2006, 679 appeals per active judge were terminated on the merits. Only the Atlanta-based 11th Circuit, with 877, and the New Orleans-based 5th Circuit, with 836, ranked higher. The D.C. Circuit had the fewest, at 173. The national average was 539.

But the 4th Circuit granted oral argument in less than 12 percent of its cases in 2006, far and away the smallest percentage of any circuit in the country. The average for all circuits was nearly 26 percent. That same year, the circuit also issued the lowest percentage of published opinions, at just over 6 percent. The average for all circuits was just under 16 percent.

Chief Judge Karen J. Williams, a 1992 appointee of the first President Bush, says the court is making the best of a bad situation.

The circuit has been able to stay current with its workload so far without suffering any loss in quality—in part by relying on its senior judges, and by inviting trial judges in the 4th Circuit and senior judges from other circuits to sit by designation, she says.

But she also says it won’t be able to do so indefinitely. “While we can continue to get our work done in a timely manner for the near future, over time the vacancies on our court, if not filled, may begin to have an adverse effect,” she says.

STATS ‘N’ SPATS

Predictably, liberals and conservatives point the finger of blame at each other for the impasse.

In February, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy, D-Vt., said the Senate had confirmed nearly as many Bush nominees in 30 months of Democratic control as Republicans had confirmed in their previous four years as the majority. As of Feb. 4, he said, the Senate had also confirmed a higher percentage of nominees under Bush (nearly 87 percent) than it did under Clinton (almost 75 percent).

But pick a different time frame, and the numbers can tell another story. In early April, Sen. Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania, the ranking Republican on the Judiciary Committee, noted that during the last two years of the Clinton administration, “15 circuit judges were confirmed compared to six in the past two years, so far, of the Bush administration.”

Of Bush and the Senate Republicans, Leahy said, “They seem to have short memories indeed as they whip up complaints about the pace that the Senate is confirming nominations. If President Clinton’s judicial nominees had received the fair treatment we have given to President Bush’s nominees in the last seven years, judicial vacancies at the end of his administration would not have been at record high levels.”

Nan Aron, president of the liberal judicial watchdog group Alliance for Justice, says that the president is more concerned about “mollifying his conservative base by picking a fight with the Senate over ultraconservative nominees” than he is about filling vacancies on an understaffed court.

Bush countered that the confirmation process has become so partisan and mean-spirited that qualified candidates are refusing to be considered because they don’t want to go through the “search and destroy” missions that those hearings often become. He said Senate Democrats have imposed a new standard on nominees, under which even a qualified candidate who has the support of a majority can be blocked from even getting a hearing by a minority of “obstructionists.”

Curt Levey, executive director of the Committee for Justice, which exists in part to defend and promote what it calls “constitutionalist” judicial nominees to the federal courts, blames Senate Democrats’ dogged adherence to the “blue slip rule,” which allows a home-state senator to block nominations to circuit seats “belonging” to that state. He chides Senate Democrats for rejecting nominees solely on ideology, something he claims Republicans never did when they were in the majority. “The Democrats apparently don’t want to confirm anybody who’s even a little conservative these days,” Levey says.

Academics say there is enough blame to spread around. The president has taken too long to nominate candidates for some openings, has chosen some highly controversial nominees, doesn’t always consult with a nominee’s home-state senators, and tends to stick by a nominee long after it becomes clear he or she will never be confirmed, they say.

“When you consider how important the 4th Circuit has been to this administration, or should be, you would think the president would put more of a priority on getting his nominees confirmed, rather than just sitting around and waiting for it to happen,” says University of Pittsburgh law professor Arthur Hellman, an authority on the federal appeals courts.

But Senate Democrats share responsibility. They’ve been deliberate to the extreme on some of Bush’s nominations, a practice critics deride as “slow-walking” nominees through the confirmation process.

“The pace at which the Senate Judiciary Committee has been moving on some of these nominations has just been glacial,” Hellman says.

Bush, for his part, may finally be listening to his critics. Agee, his most recent 4th Circuit nominee, is a highly regarded consensus candidate who has the support of Virginia’s two senators.

But some experts think that it is too little, too late. In the midst of an election year, with both sides scarred by years of nomination battles, a real resolution of the 4th Circuit logjam will likely have to wait until a single party controls both the presidency and the Senate.

What are the chances of a breakthrough before that? Indiana University law professor Charles Geyh puts it in simple terms.

“Not a snowball’s chance in hell.”

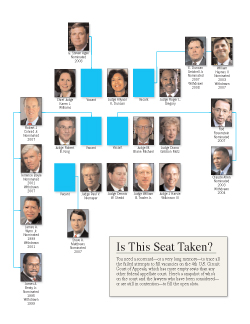

Sidebar

You need a scorecard (PDF)—or a very long memory—to trace all the failed attempts to fill vacancies on the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which has more empty seats than any other federal appellate court. Here’s a snapshot of who’s on the court and the lawyers who have been considered—or are still in contention—to fill the open slots.