Letters of the Law: National Security Letters Help the FBI Stamp Out Terrorism But Some Disapprove

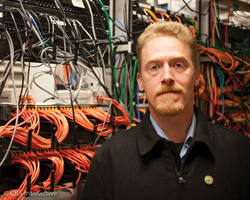

Nicholas Merrill, who challenged an FBI demand for private records about his Internet company’s clients, is now working on creating a surveillance-resistant ISP. Photo by Sarah Tew/CNET.

When Nicholas Merrill answered the door at Calyx, his Manhattan Internet company in February 2004, he encountered an FBI agent, who pulled a letter from his coat.

It instructed Merrill to surrender at least 16 categories of “electronic communication transactional records”—detailed private records including billing notices, email addresses and account numbers—about his clients.

“I opened [the letter] in [the agent’s] presence,” Merrill said in a TV interview with Democracy Now. “It was very broad. There were no instructions on how to appeal, no instructions on contacting a lawyer.”

Merrill, who opened Calyx in 1994, is a techie, not a lawyer. But two items in the letter struck him as questionable. The first was a warning not to disclose the letter or its content to anyone. The second was the lack of a judge’s signature. “It seemed to be acting like a search warrant, but it wasn’t a search warrant signed by a judge,” he told the Washington Post in 2010.

“I know the Constitution,” Merrill told Democracy Now. “The government needs to prove probable cause and go to a judge in order to search.”

In Merrill’s hand was a national security letter, a subpoena issued by the FBI for terrorism and espionage investigations. As he noted, NSLs differ from search warrants. Search warrants require a magistrate to find probable cause. To order an NSL, an FBI special agent or senior official must simply draft a letter certifying that the targeted information pertains to clandestine intelligence activities or international terrorism.

Congress created the NSL in 1986 as part of the Right to Financial Privacy Act and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, allowing FBI probes of subscriber information, account records, and telephone and electronic communication data.

In the 1990s Congress added NSL provisions to two more statutes; and in 2001 with passage of the USA Patriot Act, Congress strengthened NSLs, allowing FBI field offices to issue them, rather than just the FBI headquarters. It also eliminated the requirement that the information pertain to a foreign power, added terrorism investigations and forbade NSLs in any probe based on First Amendment activities.

The amendments “allowed NSL authority to be employed more quickly (without the delays … from FBI headquarters) and more widely (without requiring that the information pertain to a foreign power or its agents),” according to a 2009 study by the Congressional Research Service.

But the Patriot Act has also allowed the NSL to become the investigative tool of choice. In 2000, before the statute, the FBI issued about 8,500 requests, according to a 2008 report by the Justice Department’s Office of the Inspector General.

By 2003, the number of requests ballooned to more than 39,000; in 2004, there were 56,000 requests; 47,000 in 2005; and 49,000 in 2006. Overall, from 2003 to 2006, the FBI issued more than 44,000 letters containing 192,000 requests for information.

The report also showed that the percentage of requests involving U.S. citizens, as opposed to noncitizens, jumped from 39 percent of NSL requests in 2003 to 57 percent in 2006.

Among the recipients was Merrill. “The letter asked for what I believe to be constitutionally protected information belonging to my clients,” he told Democracy Now. “A lot of my clients had nothing to do with politics. They were just businesses. … Ikea, Snapple ice tea, Mitsubishi.” Others were nonprofit agencies like the New York Civil Liberties Union.

And then there was the gag order, the requirement that he refrain from imparting the slightest bit of information to anyone. “Every time I say something about it I have this knee-jerk reaction that I’m not supposed to say something about that, and that got so ingrained into me that it got a little bit strange,” he said.

Thanks to a July 2010 settlement with the government, Merrill is now permitted to identify himself as the letter’s recipient, but he still must keep details of the probe under wraps. He’s not allowed to ask about the target of the investigation and he can’t even hint about which of his 200 clients the FBI was targeting.

When he received the letter in 2004, “it didn’t seem to me that it was legal. I’ve been reading about all the powers under the Patriot Act and it didn’t seem I had much choice but to say something about it.”

So he did. “I took a leap of faith,” Merrill said. “I’m an American; I always have a right to talk to a lawyer.” And a right to file a lawsuit.

In August 2004, with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, Merrill—using the legal alias John Doe—filed suit in federal court in the Southern District of New York. He claimed that the requirement to provide the FBI with private information violated the First and Fourth Amendments, and that the nondisclosure element also violated the First Amendment.

In December 2008, the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at New York City ruled in Doe v. Mukasey that it was up to the FBI, not the recipient of the NSL, to initiate judicial review of any gag order. The court also said that a high-ranking official’s statement to a court that disclosure may endanger national security was not conclusive proof for a gag order.

While the case was being decided, Congress amended the law to allow recipients to challenge NSLs and gag orders. And it required the FBI to prove in court that disclosure of an NSL would harm a national security case.

Merrill is somewhat mollified. “The courts agreed, but the NSLs and gag orders live on,” he told the Post.

BEYOND BOUNDARIES

Others are still dubious. ACLU lawyers Michael German and Michelle Richardson fault the expansive Patriot Act for “significantly broadening the FBI’s authority.” That, “combined with the FBI’s disrespect for legal boundaries and its seeming inability to self-police,” has led to abuse of NSLs, the two say in their essay in the book Patriots Debate: Contemporary Issues in National Security Law, published this summer by the American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on Law and National Security.

“The fundamental problem,” the two write in their essay, “remains the FBI’s overbroad authority to obtain sensitive information relating to innocent people unilaterally without court review and without demonstrating any nexus to terrorism.”

But Valerie Caproni and Steven Siegel insist that the FBI needs NSLs “to appropriately and efficiently investigate threats to the national security … without alerting the targets that it is doing so.”

In their Patriots Debate essay, Caproni and Siegel, both former FBI lawyers, admit that the NSL is the “national security tool that critics love to hate, [but] when one focuses on reality rather than hyperbole” the NSL is “reasonably used and necessary” in national security investigations.

The ABA committee invited all four experts to participate in the discussions.

German and Richardson base part of their argument on reports by the DOJ Inspector General’s Office. For example, in March 2007, the inspector general told the House Judiciary Committee that the FBI violated policies as many as 3,000 times since 2003, according to the Washington Post.

The story also reported 600 cases of “serious misconduct” involving improper use of NSLs to compel phone companies, banks and credit institutions to produce records.

In addition, according to the inspector general’s March 2008 report, an FBI field review identified violations that should have been reported to the president’s Internal Oversight Board in 9.43 percent of the cases examined. The Post reported that the inspector general’s audit re-examined the files and found three times as many violations as the FBI did.

“This sort of broad, suspicionless collection of private data about innocent Americans is the logical result of destroying the requirement of a factual nexus between the NSL and terrorist activity,” German and Richardson write.

The investigation of individuals several levels from the NSL recipient bothers the experts.

Read all the articles in the Patriot Debate series:

WAR POWERS

- • Constitutional Dilemma: The Power to Declare War Is Deeply Rooted in American History by Richard Brust

- • War Powers Belong to the President by John Yoo

- • Only Congress Can Declare War by Louis Fisher

TARGETED KILLINGS

- • Uneasy Targets: How Justifying the Killing of Terrorists Has Become a Major Policy Debate by Richard Brust

- • Targeted Killing Is Lawful If Conducted in Accordance with the Rule of Law by Amos N. Guiora and Monica Hakimi

CYBERWARFARE

- • Cyberattacks: Computer Warfare Looms as Next Big Conflict in International Law by Richard Brust

- • What Is the Role of Lawyers in Cyberwarfare? by Stewart A. Baker and Charles J. Dunlap Jr.

COERCED INTERROGATIONS

- • Probing Questions: Experts Debate the Need to Create Exceptions to Rules on Coerced Confessions by Richard Brust

- • Should We Create Exceptions to Rules Regarding Coerced Interrogation of Terrorism Suspects? by Norman Abrams and Christopher Slobogin

DOMESTIC TERRORISM

- • Insider Threats: Experts Try to Balance the Constitution with Law Enforcement to Find Terrorists by Richard Brust

- • The Threat from Within: What Is the Scope of Homegrown Terrorism? by Gordon Lederman and Kate Martin

THIRD-PARTY DOCTRINE

- • Crashing the Third Party: Experts Weigh How Far the Government Can Go in Reading Your Email by Richard Brust

- • The Data Question: Should the Third-Party Records Doctrine Be Revisited? by Orin Kerr and Greg Nojeim

NATIONAL SECURITY LETTERS

- • Letters of the Law: National Security Letters Help the FBI Stamp Out Terrorism But Some Disapprove by Richard Brust

- • National Security Letters: Building Blocks for Investigations or Intrusive Tools? Michael German and Michelle Richardson, and Valerie Caproni and Steven Siegel

DETENTION POLICY

- • Detention Dilemma: As D.C. Circuit Considers Guantanamo Inmates, Can Judicial Review Harm Military? by Richard Brust

- • Detention Policies: What Role for Judicial Review? by Stephen I. Vladeck and Greg Jacob

“These people are two and three times removed,” German says in an interview. Agents “get information not just on people they call but on people [that those people] call. It’s become a data collection tool. It should be a tool to investigate rather than a tool to get as much information as it can.”

German is no stranger to the FBI. Before joining the ACLU he was a special agent from 1988 to 2004. He taught counterterrorism at the FBI National Academy and worked undercover against white supremacist and militant groups.

Richardson is an ACLU legislative counsel who monitors the Patriot Act, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act and similar security issues. Before joining the ACLU in 2006, she served for three years as counsel to the House Judiciary Committee.

The two argue that NSLs should have some of the same limits as a grand jury subpoena. A grand jury’s power, they argue, is “limited by its narrow function of determining whether to bring an indictment for a criminal violation.” That “reduces the risk of unnecessary, suspicionless data collection.”

And, German and Richardson write, prosecutors are “bound by the ethical obligations of their profession … a curb against law enforcement overreach.” By contrast, the FBI lacks such independent oversight.

Moreover, the grand jury marks the beginning of the criminal justice process and is accompanied by such obligations as the exclusionary rule, limiting illegally obtained evidence. The NSLs, the writers said, are “intrusive tools,” which, along with the Patriot Act’s expanded authority, give the FBI the capability of extensive data collection.

SEEING PARALLELS

“The founders,” German and Richardson write, “designed our constitutional system of government to prevent abuse of power … [through] robust procedural protections where the government attempts to deprive an individual of his rights.”

“Administration officials say if there is one bad apple” that doesn’t count as abuse, says Richardson in a phone interview. “But that’s not necessarily what we are talking about. To us, the bigger problem is: Should our government be collecting these records? We say no.”

Caproni and Siegel argue that national security letters compare more favorably with the grand jury system than German and Richardson allow. Where grand jury subpoenas can permit collection of “any nonprivileged document from any person or entity, the FBI can use NSLs only to obtain a very narrow range of information from a very narrow range of third-party businesses,” they argue. Where grand jury subpoenas can be used in “any sort of criminal case, NSLs can only be used during duly authorized national security investigations.” While almost any federal prosecutor can issue a grand jury subpoena, NSLs are limited to very high-level FBI approval.

“It’s not a rubber stamp,” says Siegel in a phone interview. “You have to go through several levels of the FBI and additional legal review. A lot are shot down.”

Caproni and Siegel also argue that information collected with NSLs is constitutionally permissible: In United States v. Miller, decided in 1976, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that there is no reasonable expectation of privacy in third-party data. They also criticize as hyperbole the notion that NSLs are behind any overreach during investigations, saying that most material obtained via national security letters would also be obtainable with a subpoena.

Both Caproni and Siegel have worked as FBI counsel. Caproni, now deputy general counsel of Northrop Grumman Corp., worked for the U.S. attorney’s office supervising cases of organized crime, narcotics, white-collar crime and civil rights. She left to work for the Securities and Exchange Commission, but was later appointed FBI general counsel, where she helped transform the agency after 9/11 to perform domestic intelligence. Siegel, who also works for Northrop Grumman, was a state and federal prosecutor before joining the FBI, where he was involved in counterterrorism and national security issues.

Caproni and Siegel also argue that the inspector general’s reports on NSLs haven’t been as damning as German and Richardson suggest. In a 2007 report, for instance, the inspector general found no “misuse in … using NSLs maliciously or inappropriately.”

The report found errors in either the issuing of NSLs or the handling of data in 7.5 percent of NSLs it sampled. But half were third-party errors—the recipient provided information the FBI did not seek. Setting those aside, the FBI’s actual error rate was 4 percent, and most of those were nonsubstantive errors, Caproni and Siegel contend. For example, the certification language was different from the statutory requirement. Only two NSLs of those sampled were substantive.

“One must question,” Caproni and Siegel argue, “whether two substantive errors out of 293 NSLs can fairly be characterized as ‘pervasive.’ ” The writers also maintain that German and Richardson avoid discussing the controls now in place to avoid the kinds of errors cited by the inspector general: High-ranking FBI officials must issue NSLs; the letters are created using an “automated workflow system that minimizes the potential for error”; and all employees must be trained to understand the rules.

As for the violations found in the FBI field review, Caproni and Siegel say the 9.3 percent figure represents “potential” violations, many of which also involve third-party errors.

But it’s the gag order that leaves letter recipients like Merrill confused about accountability and purpose. Caproni and Siegel write that 97 percent of NSLs have a similar nondisclosure requirement. Its purpose is to keep suspected terrorists, for example, from accelerating any plans for mayhem once they learn they are being investigated. Even so, the statute allows recipients a challenge if it is unreasonable, oppressive and otherwise unlawful, the pair note.

Nevertheless, German says, “it’s long overdue to have a top to bottom review of all the intelligence authorities” that Congress has created since 9/11. The government needs to determine whether the NSL was a valuable tool. “It has an impact on privacy, so if it’s not a very effective tool, let’s develop a tool that is.”

As for the allegation that the FBI uses NSLs indiscriminately to gather information, Siegel suggests that a call from an al-Qaida member in Minneapolis may be connected to a plot in New York. “You clearly need information to connect the dots,” he says. “But you can’t use an NSL for whatever purpose you want. It is a carefully thought-out procedure.”

One provision that may need review, says Siegel, is the section governing electronic communication transactional records—the information the FBI sought from Merrill. The statute lets agents investigate “subscriber information and toll billing records information.”

But, Siegel says, “a billing record used to be the bill you paid on a phone. Now there are so many providers offering different” plans—cellphones, email, etc. “You don’t just pay for long distance anymore,” he says.

For Merrill, the battle goes on. He recently established the Calyx Institute, a nonprofit Internet service provider that uses data encryption to prevent anyone other than the user—or even the ISP itself—from seeing others’ Internet activity.

He’s seeking $1 million to launch the operation.

“I am grateful for the outpouring of support,” Merrill told CNet, “which I think clearly demonstrates that there is a vast public demand for privacy-conscious telecommunications companies.”