Legal ethics questions and accusations of spying have stymied Guantanamo terrorism trial

Editor’s note: A ruling by the Court of Military Commission Review on this case was not available to the ABA Journal before its press deadline. Read our story detailing the most recent developments.

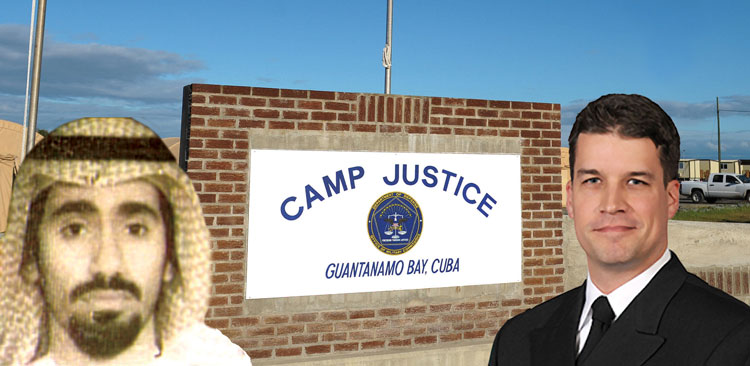

In 2000, two members of al-Qaida bombed the U.S. Navy destroyer the USS Cole in a suicide attack, killing 17 sailors and wounding 39 others. Two years later, Saudi national Abd al-Rahim Hussein Muhammad al-Nashiri was arrested for orchestrating the crime and turned over to the U.S. government.

Al-Nashiri spent the next four years at CIA “black sites” overseas, eventually ending up at the infamous U.S. prison for terrorists at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. His current trial, at which he faces the death penalty, began in 2011 and still has no end in sight.

His case was still in preliminary hearings in the fall of 2017, when al-Nashiri’s civilian defense team quit.

The bombing of the USS Cole. Photo courtesy of U.S. Navy/Getty Images

Lawyers Richard Kammen, Rosa Eliades and Mary Spears left because they found a microphone in the room where they met with their client. The government says that microphone was never turned on, but thanks in part to a history of spying on defense lawyers at Guantanamo, they didn’t trust those reassurances. After consulting a legal ethics expert, the lawyers decided they had no choice but to quit, even though that left al-Nashiri with no attorneys other than a Navy JAG, Lt. Alaric Piette, who had never tried a death penalty case. Piette politely but consistently refused to participate in most of the hearings thereafter, maintaining that he doesn’t qualify to defend a capital case under the military commissions’ own rules.

That clearly frustrated the judge, Air Force Col. Vance Spath. The judge made several unsuccessful attempts to compel the attorneys into court—including briefly imprisoning the head of defense at Guantanamo for refusing to order them back. In court, Spath repeatedly said the defense’s ethics concerns were a “strategy” intended to undermine the trial. Finally, on Feb. 16—after what he said was a sleepless night worrying about the case—Spath suspended the proceedings, saying he needed guidance from a higher court.

That guidance may be coming, but observers say it’ll be slow—first a trip to the Court of Military Commission Review, an appeals court dedicated to Guantanamo cases, and then a nearly inevitable appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Meanwhile, both al-Nashiri and the Cole victims have been waiting for some kind of outcome for most of the 21st century. That’s not unusual for the Guantanamo military commissions—and under those circumstances, some are wondering whether the commissions are still a good idea.

“I think that if this is the way the Military Commissions Act system was intended to function, then somebody ought to take a fresh look at the Military Commissions Act, because the current arrangement is unfair to the families who lost loved ones,” says Eugene R. Fidell, who teaches military justice at Yale Law School and co-founded the National Institute of Military Justice.

Espionage

The Cole was docked for refueling in Aden, Yemen, on the day of the bombing. Members of the crew were lining up for lunch when a small boat pulled up alongside the much bigger ship. It was so close that sailors on watch said hello to the two pilots.

Photos courtesy of Newsmakers/D.C. Everest School District & Yale Law School.

Then the explosion came. Those who made it out alive describe chaos afterward as water rushed in and the crew scrambled to survive. One sailor told the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot in 2010 that he had to swim out into the harbor, glasses blown off and eardrums ruptured, as water rushed into the ship.

Two years later, authorities in Dubai arrested al-Nashiri, believed to belong to al-Qaida, and turned him over to the United States. For the next four years, he was transferred around CIA “black ops” sites—overseas prisons loaned to the U.S. by foreign governments, where he was subjected to interrogations federal authorities believed fell short of the definition of torture. Those included waterboarding al-Nashiri at least three times; stripping him and shaving him; shackling his arms over his head for extended periods to deprive him of sleep; and force-feeding him rectally. According to a CIA report declassified in 2014, this treatment resulted in “essentially no actionable information.”

In 2006, al-Nashiri was transferred to the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, where he was eventually charged with orchestrating the Cole bombing, as well as the suicide bombing of the French tanker MV Limburg. From the beginning, his legal team included Kammen, an experienced death penalty defense lawyer from Indiana who filled the statutorily required role of “learned counsel.” By the summer of 2017, the team also included Piette, the Navy attorney, and assistant defense counsel Eliades and Spears, both currently at the Military Commissions Defense Organization.

A prosecution filing obtained by the Miami Herald’s Carol Rosenberg (who won a 2018 ABA Silver Gavel Award for her Guantanamo reporting) details how that team found the microphone where they met with al-Nashiri. After defense lawyers discovered that a different meeting room for defense lawyers had been bugged, military authorities invited the al-Nashiri defense team to have a look at their own room. Piette didn’t expect to find anything.

Eugene Fidell: “I think that if this is the way the military commissions act system was intended to function, then somebody ought to take a fresh look at the Military Commissions Act.” Photo by Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images

“It’s difficult to imagine a lawyer for the CIA signing off on something like that,” says Piette, who is stationed in Virginia. “Or any intelligence agency.”

But they found the microphone. The prosecution filing, dated March 5, explained it was a “legacy microphone” left over from when the room was used for interrogations, and asserts that it was “not connected to any listening/recording device.”

Kammen did not believe this, in part because of a long history of interference in the work of Guantanamo defense lawyers. As he detailed in a later filing in Indiana federal court, the base openly read detainees’ legal mail for two years. In 2013, there was a two-month recess in al-Nashiri’s trial because the government had been caught reading his defense team’s email. The military had monitored defense lawyers’ on-base internet use and sent some of their files to the prosecution. And in 2014, the FBI recruited a member of the civilian defense team for Ramzi bin al-Shibh, who is accused of helping plan the Sept. 11 attacks.

Piette would have liked to see something demonstrating that there was no spying. Unfortunately, Guantanamo authorities dismantled the room two months after the discovery, removing any chance of independently verifying the government’s claims. That happened after Spath denied the defense team’s request to investigate the microphone and hold a hearing on the matter.

Spath’s reasoning remains classified, but he’s said in court that declassifying it would prove his decisions right. (Both Spath and the prosecution team declined to speak to the ABA Journal.) Kammen and Piette strongly disagree. Piette likens his reaction to the incredulous looks frequently assumed by the character Jim from the NBC sitcom The Office.

“I made this little meme … of the judge saying that, and then me, and it was Jim’s face looking at the camera,” he says. “Because how could you think that if this stuff is declassified, anybody is going to be on your side?”

This article was published in the November 2018 ABA Journal magazine with the title "A Military Injustice."

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.