What do falling bar-passage rates mean for legal education--and the future of the profession?

Erica Moeser. Photograph by Tony Avelar.

David Frakt is a lawyer, a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force Reserve and a former law professor who has studied the relationship between LSAT scores, undergraduate grades, law school performance and bar passage rates. But he may be better known as the candidate for dean of the Florida Coastal School of Law in Jacksonville (which had a July 2015 first-time bar pass rate of 59.3 percent) who was asked to leave the campus in the middle of his presentation to faculty and staff. He had dared to suggest that the school was risking its accreditation by admitting too many students with little or no chance of ever becoming lawyers.

Frakt concedes that some applicants with modest academic qualifications can excel in both law school and practice, but he says there’s a point below which a candidate’s aptitude for legal studies and legal reasoning is highly predictive of failure.

“However dedicated and skilled law professors and academic support staff may be,” Frakt maintains, “there is only so much they can do with students with no real aptitude for the study of law. They are not miracle workers.”

Frakt was shown the door in 2014, which may seem to be old news. The problem is that much of current bar passage news isn’t much different. To be plain, it has been lousy:

• The mean test score on the February administration of the Multistate Bar Examination fell significantly for the fourth consecutive time, down 1.2 points from 2015 to a dismal 135—its lowest score since 1983.

• February’s decline followed an even bigger drop in the average score on the July 2015 administration of the exam, which fell 1.6 points from July 2014 to 139.9, its lowest level since 1988. (July and February results are not comparable because the test pool is smaller and has more repeat test-takers.)

• And last year’s poor showing followed the single biggest year-to-year drop in the average MBE score in the four-decade history of the test, from 144.3 in 2013 to 141.5 in 2014.

The numbers don’t lie, but proffered explanations for the descent in bar exam scores leave serious questions about what’s happening with law school admissions, legal education and even the quality of legal representation in the future.

The ongoing downward slide in MBE scores comes as no surprise to Erica Moeser, president of the National Conference of Bar Examiners, the Madison, Wisconsin-based nonprofit that developed and scores the 200-question multiple choice test, part of every state’s bar exam except Louisiana’s.

Moeser says the cause of the current slump is “deceptively simple.” So simple, in fact, that she doesn’t know how anybody could think otherwise. It started, she believes, with the sharp drop in law school applications that began in 2011, when the job market for newly minted lawyers dried up, and would-be students—hearing horror stories about new graduates with six-figure debts who couldn’t find jobs—turned to other post-grad-degree fields such as business or medicine.

That was the same year, not coincidentally, that the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar began requiring schools to disclose more detailed—and more meaningful—information about law graduate employment outcomes.

The drop-off in demand forced many schools to dip deeper into the applicant pool to fill their incoming classes, Moeser says, admitting students with weaker academic credentials—primarily Law School Admission Test scores and undergraduate grade point averages—than they had ever previously accepted.

Because LSAT scores correlate strongly with MBE performance, which accounts for half of the grade on most bar exams, Moeser says, it was almost inevitable that the students who started law school in 2011 (most of whom would have taken the bar exam in 2014) would perform worse than the graduates who sat for exam the year before.

And since both enrollments and the LSAT profiles of incoming classes have continued to fall every year since 2011, she says, there’s no reason to think that bar pass rates will improve any time soon.

“Why that would surprise anybody is surprising to me,” she says. “What would surprise me is if LSAT scores dropped and bar pass rates didn’t go down.”

THE DISSENTERS

But other legal education experts argue the relationship between LSAT scores and bar pass rates is anything but simple. There are those—including the Law School Admission Council, which administers the LSAT, legal education section officials and many law school deans—who don’t subscribe to Moeser’s theory that a drop in the former necessarily leads to a decline in the latter.

While the council says the LSAT is a valid measure of certain cognitive skills important to success in law school, it insists the test should not be used to predict bar pass rates.

“The LSAT was designed to serve admission functions only,” according to one of its cautionary policies. “It has not been validated for any other purpose.”

And section officials say Moeser’s premise may well be true, but it has never been proven. While LSAT scores in general have some predictive value, they say, they can be way off with respect to some people. Besides, every state’s bar exam is different. And some schools are better than others at turning applicants with low academic predictors into successful lawyers.

“Just because academic credentials and bar pass rates have gone down at the same time doesn’t mean that one caused the other,” says Bill Adams, the section’s deputy managing director.

And some law school deans say Moeser is flat-out wrong.

“The facts don’t support her premise that greedy law schools are filling their seats with unqualified students,” says Nick Allard, president and dean of Brooklyn Law School (which had a July 2015 first-time bar pass rate of 84.5 percent).

So goes the debate, while potential students, law schools and future employers watch and wonder: When will the descent stop?

A WARNING

Moeser says she never intended to become a lightning rod for the issues roiling legal education. She only wanted to warn deans about what she and her staff were witnessing when they tabulated the results from the July 2014 exam.

So she sent the deans a memo expressing her concern over the drop in scores and assuring them that the results, which had been checked and rechecked, were correct: “All [indicators] point to the fact that the group that sat in July 2014 was less able than the group that sat in July 2013,” she wrote.

The phrase less able struck a nerve with many deans, who demanded an investigation into the “integrity and fairness” of the test and the release of all data the National Conference of Bar Examiners had relied on for that less-able determination.

Nick Allard. Photograph Provided by Brooklyn Law School.

But Moeser rebuffed them: While she regretted using the term, she remained confident in the correctness of the reported scores.

Critics at first blamed the poor showing on a software glitch affecting test-takers in 43 states, who had trouble uploading their answers on the essay portion of the test the evening before they took the MBE. But Moeser said the NCBE’s research found no differences in the results between test-takers in jurisdictions that had used the software and those that didn’t.

When last year’s national mean score took another dip, critics blamed the addition of a seventh subject, civil procedure, to the exam beginning with the February 2015 administration. But Moeser once again rebuffed them, citing internal data indicating the seventh subject had no impact on test-takers’ performance. She also suggested that nobody should have been surprised to hear that the MBE now included questions on civil procedure, which has been part of every state’s bar exam for as long as anyone can remember.

Then critics began to question the content of the exam, contending that it doesn’t test the right things or that it doesn’t test things that are relevant to a lawyer’s daily practice. Some, including Allard, have even suggested doing away with a bar exam altogether.

But Moeser says the material included on the MBE has been put together by a team of volunteer experts and has been validated by a 2012 job analysis commissioned by the NCBE into what new lawyers say they do and what they need to know to do it.

And she wonders why anybody would suggest doing away with the exam, which she considers an indispensable consumer safeguard against unqualified practitioners.

“Why we would allow anybody to become licensed without an entry-level assessment of their abilities is beyond me,” she says.

ENTRY EXAM

For the vast majority of law school applicants, the LSAT is a hassle they must hurdle.

LSAT scores are converted to a scale of 120 to 180 through a process known as equating, which adjusts for the difference in difficulty between tests. Every LSAT score is reported with a percentile rank, which reflects the percentage of test-takers scoring below a reported score based on the three-year-prior period. Score 180, the 99.9th percentile, and you’d beat 99.9 percent of all test-takers for the 2012-2015 test cycle. Score 152 and you would be in the 51st percentile.

Moeser has been tracking changes in schools’ first-year enrollment and the reported LSAT scores of incoming classes in the bottom quarter of the class. Students at that level and below are most likely to struggle on the bar exam and to experience disappointment in the job market, she notes. They are also the students who are most likely to pay the full sticker price of their legal education: Students with higher scores are more likely to be courted with tuition discounts.

Her staff analysis shows no schools have been getting both higher LSAT scores at the top of the bottom quarter of new students and increased enrollment.

“The fact that there are no schools in that quadrant suggests there’s a problem,” she says.

Moeser believes her assessment has been vindicated by others, including Jerome Organ, a law professor at the University of St. Thomas (bar pass rate of 83.05 percent) in Minneapolis, Minnesota, who studies changes in law school demographics.

Organ has documented the decline in entering class credentials over the past six years, noting both a decrease in the percentage of students with LSAT scores above 160 and a corresponding increase in the percentage of students below 150. He says the percentage of high scorers has dropped from about 41 percent in 2010 to 32 percent in 2015, while the percentage of low scorers has risen from about 14 percent to 24 percent.

And for law schools, Organ’s research shows, the lower-scoring pool means more schools have a lower average score for the entering class. The number of schools with about half their new students scoring 160 or more fell by more than one third, from 77 in 2010 to 49 in 2015. And the number of law schools with a quarter of the entrants’ LSAT scores below 150 more than doubled, from 30 to 75.

The number 145 used to be quite a meaningful point in LSAT scores—six years ago. Organ says, no law school had an entering class with a median LSAT score below 145, and only four schools had bottom-quarter LSAT scores below 145. Last year, there were seven schools with median LSAT scores below 145 and 23 with bottom-quarter LSAT scores below 145.

But though Organ says he generally agrees with Moeser, he believes that at least some of the bar pass rate decline is due to the 2014 software glitch and that subject added to the MBE last year, which he says has arguably made the test tougher.

Derek Muller, a professor at the Pepperdine University School of Law (bar pass rate of 68.7 percent), now believes the decline in the quality of the applicant pool is largely responsible for the drop in bar exam scores. Once a doubter, he now worries that the July 2014 test results show the beginning of a troubling trend. Pepperdine’s first-time bar pass rate dropped nearly three percentage points between 2013 and 2014, and another nine percentage points between 2014 and 2015, but was still just above California’s statewide average of 68.2 percent.

Because the graduating classes of 2016, 2017 and 2018 have had incrementally worse applicant profiles than the graduating classes of 2014 and 2015, Muller says, the news going forward is grim.

“Whether other factors have contributed to the drop in bar pass rates remains an open question,” he says, “but the continuing decline in student quality suggests this is not a one-time thing, but a structural and long-term issue with significant consequences for legal education and the profession.”

reports of war

In a report released last year, Kyle McEntee, a dedicated advocate for legal education reform, tossed a bomb:

“We cannot allow an increasing number of law students to enroll in a quest that is unlikely to succeed when the stakes are so high,” according to a report issued by McEntee’s watchdog organization Law School Transparency. “Declining LSAT scores of admitted students is the first indicator of a potential bar passage disaster that won’t be evident for three years to the students who are affected and four years to the ABA.”

The report drew a strong rebuke from the LSAC. Its president, Daniel Bernstine, issued a press release saying the findings were based on “misunderstandings” and “demonstrably false” claims. Bernstine cited (PDF) the LSAC’s test-use guidelines, which say the LSAT does not measure all of the attributes that can predict the probability of eventual bar passage or professional success. He also said the LSAC has long cautioned against drawing conclusions from such fine distinctions in LSAT scores.

But McEntee, the Law School Transparency executive director, and David Frakt, who chairs its national advisory council, defended their report, which they said had been very careful to explain that the risks of a low LSAT score could be offset by a strong academic performance or a law school’s ability to educate students with marginal academic predictors. And they challenged schools to publicly release the internal data they use in making admissions decisions.

“LST should not be criticized for pointing out uncomfortable truths,” they wrote in a response to Bernstine on the Faculty Lounge blog. “Until LSAC, or the law schools identified by LST as having problematic admissions practices, comes forward with actual data to refute the conclusions in the LST report, general attacks on the validity of the report should be taken with a large grain of salt.”

Salt is not what some educators are adding to the debate.

Brooklyn’s Allard says the deans have never received a satisfactory explanation from Moeser for the biggest drop in the average MBE score in recorded history. He also says Moeser’s assertion that the decline in student quality is the reason has never been proven and that she has no data to back it up.

He says there are much better predictors of law school performance than the LSAT, including undergraduate GPAs, law school grades and post-undergraduate work experience. And he insists his school’s students are “every bit as qualified” today as they ever were, if not more so.

But the bottom-quarter LSAT score of Brooklyn’s incoming class has dropped 10 points since 2010, from 162 then to 152 last year. And he had no ready explanation for why his school’s graduates’ first-time bar pass rate fell 9.5 percentage points, from 94 percent in 2013 to 84.5 percent in 2014, and another 3.5 points to 81 percent last year.

Allard says bar pass rates have always fluctuated. But he says his school’s pass rate has always been “very high” and remains “significantly above” the statewide average.

Instead, he says the overall drop in scores, both in New York state and nationwide, raises “fundamental questions” about whether the bar examination process “fairly and adequately” measures test-takers’ readiness to practice.

Allard suggests that both the LSAT and the bar exam have outlived their usefulness. And he says there’s no good reason why qualified graduates of ABA-approved schools should have to take a bar exam, which is very expensive, takes too long to prepare for and provides a poor measure of competence.

“Not a single lawyer would tell you that it tests anything you need to know to practice,” he says.

Charnele Tate. Photograph by Tom Salyer.

Stephen Ferruolo, dean of the University of San Diego School of Law (bar passage rate of 72 percent), says he’s still waiting for Moeser’s explanation of the scoring of the 2014 exam. Not because he wants to use it against her, he says, but to help him do his job as dean.

His school’s first-time bar pass rate has fallen from 74.6 percent in 2013, but remains above the statewide average of 68.7 percent. But he says he won’t be satisfied until it reaches 80 percent.

He also says there’s a growing disconnect between what the bar exam tests and what lawyers do in their daily practice. That disconnect will become even greater next year, he says, when the California bar exam is reduced from three days to two, keeping a full day for the MBE but cutting the amount of time devoted to performance testing from six hours to 90 minutes.

“We have a problem that needs to be fixed,” he says. “And I think we should be working together to find a solution rather than pointing fingers at one another.”

Ferruolo says nothing should be off the table for discussion, from shortening the bar exam to a few core subjects to allowing students to take it after two years of school to eliminating it altogether.

ABA STANDARDS

The ABA’s legal education section, which accredits 206 law schools, uses bar passage rates to measure a law school’s compliance with two accreditation standards: Standard 301, (the educational program); and Standard 501 (the quality of admitted students).

Standard 301 says that “a law school shall maintain a rigorous program of legal education that prepares its students upon graduation for admission to the bar and for effective, ethical and responsible participation as members of the legal profession.” Standard 501 (a) requires a law school to maintain sound admission policies and practices. And Standard 501 (b) prohibits a law school from admitting applicants “who do not appear capable of satisfactorily completing its program of legal education and being admitted to the bar.”

Factors to be considered in assessing a school’s compliance with the standard include the academic and admission test credentials of the entering class, the academic attrition, the bar passage rate and the effectiveness of the school’s academic support program.

Barry Currier, the ABA’s managing director of accreditation and legal education, says the accreditation process is not designed to make advance judgments about a school’s performance.

“Until a school puts these students through its program, we can’t possibly know how well they will perform,” he says. Some students with low academic predictors go on to become successful lawyers, he notes, and nobody wants to deprive anybody of the opportunity to try.

So the assessment process is set up to look back at how a school has performed over time with the students it admits: how many graduate, how many pass the bar, how many flunk out or leave for other than academic reasons.

The ABA re-accredits schools every seven years. The section also issues annual questionnaires the schools are required to complete. Big changes in the data are flagged for further review and may prompt an inquiry, he says.

All such inquiries are confidential unless a school is publicly sanctioned. But the section may be “in conversations” privately with some schools over their compliance with the standards. (Rebecca White Berch, chair of the section’s governing council, says more than half of all ABA-approved schools are responding to questions raised by data reported on their last questionnaires, but she hasn’t said how many of the questions are about admissions standards.)

Still, the section’s bar pass standard, by all accounts, leaves a lot to be desired. Critics say it is too lax and too ridden with loopholes to hold schools accountable for their admissions decisions. And in June, a Department of Education panel recommended the ABA be suspended from accrediting law schools for one year.

In fact, only two schools, both in California, have been placed on probation for violating the bar pass standard in the past decade or so: Whittier Law School in Costa Mesa and Golden Gate University School of Law in San Francisco. Two other provisionally approved California schools—the University of La Verne College of Law in Ontario and Western State College of Law in Irvine—were denied full accreditation over low bar pass rates; both have since been fully accredited.

A law school can meet the standard by showing its first-time bar pass rate in three of the five previous years is no more than 15 percentage points below the average for ABA-approved schools in states where its graduates took the exam. Or it can show that 75 percent of its graduates who took a bar exam in three of the five previous years passed.

The section’s governing council, responding to widespread concerns over the nationwide drop in bar pass rates, is proposing to simplify and strengthen the standards.

Under the proposed new standard, a law school would have to show that 75 percent of its graduates who take a bar exam within two years of their graduation pass.

The council is also proposing to provide a new means of enforcing the requirement that a law school only admit applicants who appear capable of graduating and being admitted to the bar. That proposal would create a rebuttable presumption that a law school with an attrition rate above 20 percent (not including transfers) is in violation of the standards.

Both proposals, if approved by the council in October, would be reviewed by the ABA House of Delegates at the 2017 midyear meeting in Miami in February. If the house concurs, the changes would take effect immediately. The House can also refer the changes back to the council for reconsideration, but the council has the final say on any amendments to the standards.

DEFYING THE NUMBERS

Kevin Cieply is president and dean of Ave Maria School of Law (bar passage rate of 47.8 percent) in Naples, Florida, which had one of the lowest entering class LSAT profiles of any school in the country in 2014, including a 25th percentile LSAT score of 139. He says the school has since taken “significant and aggressive” measures to increase its LSAT profile, including launching an ambitious recruitment campaign, creating a new scholarship program for well qualified applicants and appointing a new director of admissions steeped in experience at assessing and evaluating the academic potential of students.

Though Ave Maria has raised its median LSAT score five points in one year, it’s July 2015 first-time pass rate was down nearly nine percentage points from the year before, and the lowest among 11 schools in the state. Florida’s statewide average was 68.9 percent.

Cieply says he expects bar pass rates will improve this year and next year, but doesn’t expect to see the full effect of the changes until 2018, when last year’s entering class will graduate.

“It’s not like flipping a switch,” he says. “It doesn’t happen overnight.”

Charnele Tate, who scored in the mid-140s on her LSAT, graduated from Ave Maria in 2014, passed the bar on her first try and now works as an assistant public defender in Lee County, Florida.

Tate thinks the LSAT is good only for predicting how somebody will do on an exam. And she says she knows people who did very well on the LSAT but flunked out of law school or failed the bar exam.

Tate has about $240,000 in student loan debt, which worries her, but she hopes to take advantage of federal public service loan forgiveness program for people who work continuously in a governmental capacity and make 120 on-time payments for 10 years.

Still, she’s frustrated by the fact that many of her friends who didn’t go to law school are now making more than her, and she worries about what she will do if Congress does away with the loan forgiveness program before she puts in her 10 years.

“I try not to think about it, but it’s always in the back of my mind,” she says.

Vouching for Ave Maria’s graduates is John Schmieding, vice president and general counsel of Arthrex, a Naples-based maker of orthopedic surgical devices.

Schmieding has hired two of its students as interns, and one Ave Maria graduate is now in charge of the company’s global products liability litigation. He has met a lot of lawyers in his 20-plus years of practice, but he says none could hold a candle to her.

“They’re doing something right over there,” he says.

YEAR THREE

July’s bar pass results will begin trickling out this month, adding results to the debate over whether past declines were aberrations or the start of a worsening trend.

And, after five years of consistently bad news, things may finally be looking up for law schools. Total first-year enrollment, which had fallen 29 percent between 2010 and 2014, has essentially been flat for the past two years, dropping about 2.2 percent to around 37,000 between 2014 and 2015, ABA statistics show. And more than one-fourth of all schools raised their LSAT averages for the bottom quarter last year, including six schools with three percentage point increases, Moeser says.

And according to Organ’s analysis of application data as of early March, there may be an applicant pool of about 57,500 this fall, up about 5.5 percent from last year’s 54,500.

A Robert Half survey released in June found 31 percent of lawyers responding predicted their firms would add legal jobs in the second half of 2016. However, the previous year’s study had 29 percent of respondents predicting the same increase, and while the percentage of 2015 graduates employed in full-time, long-term, bar-passage required or preferred jobs was up slightly from 2014, the actual number of graduates hired into such positions declined by 7.3 percent, from 30,234 in 2014 to 28,029 in 2015.

Organ says part of the decline is probably attributable to dropping bar passage rates. But it may also be the result of shrinking job market conditions.

The employment numbers could be seen as a cautionary tale, Organ says, suggesting the good news for the profession on the applicant front may be short-lived.

This article originally appeared in the September 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Bar Fight: Exam passage rates have fallen, but battles over why and what it means are roiling legal education.”

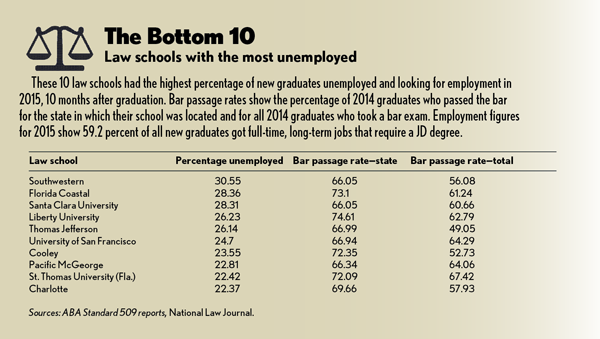

Updated on September 8 to remove a graphic with an error in it.

Correction

Print and initial online versions of “Bar Fight,” September, mistakenly identified the University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minnesota as among those law schools with a high percentage of unemployed graduates, due to an editing error. The chart “The Bottom 10” (page 53) should have named St. Thomas University School of Law in Florida, which had bar passage rates of 72.09 percent for the Florida exam and 67.42 percent for all test-takers.The Journal regrets the errors.