Legal battles over gardens are sprouting up across the country

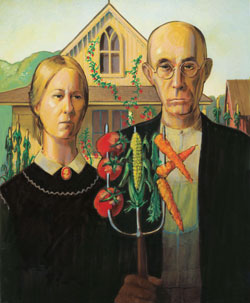

Illustration by Tom Gianni

Thanks, perhaps in part, to the green thumbprint of Michelle Obama on the White House, edible home gardens are gaining popularity. But they come with an unintended consequence: front-yard garden wars.

Front yards often have better sun, so they’ve become more appealing spots for gardeners interested in growing their own food. But vegetable gardens can look shabby, and rotting vegetables can attract rodents and insects. And all of that is enough to make a property value-concerned neighbor call in the authorities.

Citing obscure blight ordinances, neighboring homeowners have sought to remove front-yard gardens via enforcement of local laws that require manicured, homogeneous front lawns. Officials in some jurisdictions are starting to take notice.

Last November, city officials in Orlando, Fla., threatened to fine a homeowner $500 a day for not moving carrots, radishes, cilantro and other crops from his front yard.

In Ferguson, Mo., last summer, city officials ordered a homeowner to dig up his heirloom tomatoes, peppers and beans because the garden in his front yard violated a variety of zoning ordinances. John Shaw, Ferguson’s city manager, says the zoning laws and ordinances must protect the property values of all city homeowners by providing “a clear set of ‘knowns’ ” for potential buyers.

Ferguson’s ordinances aren’t intended to be punitive, he adds. Without regulation, such gardens can block sight lines for motorists and pedestrians and are vulnerable to erosion during off-seasons.

Similar battles have sprouted over the last couple of years in Michigan and Oklahoma.

This mounting urban agricultural controversy, pitting municipalities’ management scope against individual property rights, represents an “ongoing, eternal set of issues: the rights of individual owners and side effects for neighbors,” says University of San Francisco housing law professor Tim Iglesias. “There are real health and safety concerns. And aesthetics can affect property values, especially in suburbia, where people are used to conventional landscapes.”

Even if homeowners partner with organizations like the libertarian Institute for Justice, which the Orlando plaintiff did, they’ve got “a hard road to hoe” in challenging zoning laws, he says. “Courts have regularly validated local governments’ right to regulate issues related to property values. Plaintiffs must demonstrate the law is arbitrary or irrational,” Iglesias says.

He expects most cities to eventually accommodate front-yard gardens—with some regulation. After all, raising urban chickens is widely allowed even though that hobby is more likely to cause a nuisance. Many cities, including Salt Lake City and San Francisco, have already adopted or modified ordinances to permit front-yard gardens.

Sacramento, Calif., revised its zoning laws in 2007 after a long effort by food activists. Residents there can now grow vegetable gardens in front yards, provided they meet maintenance and presentation standards. Specifically, front yards must be landscaped and irrigated and have no dead plant matter taller than 4 inches.

While zoning laws are notoriously slow to change, Iglesias adds, someone will eventually draft a model ordinance; or a reasonable existing ordinance, such as Sacramento’s, will become the de facto model.

“Front-yard gardens are new concepts,” Shaw says. “Communities need to have a conversation about this topic with their residents. Sometimes governments, just like residents, have to adapt to new ways of looking at things.”

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.