Just Like Everyone

Liza Barry-Kessler

Photo by Callie Lipkin

Like many in the gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender community, Liza Barry-Kessler has never been sure of the reaction she’ll get when potential employers, supervisors, co-workers and clients learn she’s a lesbian. In the early 2000s, while working at a small lobbying firm in Washington, D.C., on issues of education, technology and the Internet, many of Barry-Kessler’s colleagues knew she was gay. But the issue was never discussed, and she sensed it was best not to mention it to clients.

“This was during the big debates about blocking Internet materials harmful to minors, and the big concerns were child pornography and sexual predation,” Barry-Kessler says. “I felt like I couldn’t be as out, not so much in my day-to-day job but in terms of the clients we worked with.

“That wasn’t something anyone ever said—the people I worked with weren’t homophobic. But there was an additional level of hypersensitivity to the possibility that it would look somehow off-putting to the clients.”

In 2003 with new employer AOL, then based in Dulles, Va., Barry-Kessler got an entirely different reception when she returned from her honeymoon after a non-state-sanctioned wedding.

“It blew my mind,” Barry-Kessler says. “My co-workers did whatever they’d have done for anybody else getting married. They decorated my cubicle, everybody contributed to a gift, and they had a cake for me. It was better than I’d hoped for. It was treated as normal.”

That simple, thoughtful response reflects a growing movement among legal employers that strives not just for diversity, but for the inclusion of GLBT and other minority employees in everyday office life.

Legal employers are increasingly realizing that their efforts at creating diversity—simply recruiting a certain number of GLBT attorneys every year—has resulted in little growth in the number of such lawyers who stay long term and move into leadership ranks. So some have shifted their focus to creating workplaces in which GLBT and other minority candidates feel understood, appreciated and respected. The expectation is that those attorneys will be more creative and productive and less likely to move on.

Kathleen Nalty

Photo by John Johnston

“If you create inclusiveness, you’ll solve your diversity issues,” contends Kathleen Nalty, executive director of the Colorado Campaign for Inclusive Excellence, a Denver nonprofit that is overseeing a pilot program to help 10 legal employers build inclusive workplaces.

“The focus has always been on the front end, getting people in the door,” she says. “But if you focus on the back end, people will come and you won’t have them leaving.

“It intuitively makes sense. People will want to come to a place that’s inclusive, and they’ll thrive there.”

Undercover Initiative

When Therese M. Stewart began practicing law about 30 years ago, she was a member of a covert group of about 1,000 GLBT attorneys called the Bay Area Lawyers for Individual Freedom. The membership roster was kept under wraps.

In the mid-1980s “we did a survey and got back about 300 responses,” says Stewart, who is now chief deputy city attorney for San Francisco. “The vast majority said they worked in small firms, nonprofits or government because they didn’t want to hide their identities or cope with the burden of dealing with an issue that wasn’t comfortable. The big firms weren’t, by and large, gay friendly.”

GLBT lawyers have come a long way from those days, but many still make individual calculations about how much personal information they can safely reveal at work.

“One of the most obvious places where issues arise concerning sexual orientation is at the recruiting stage,” Stewart says. “It somewhat frequently arises when recruits have done work related to their GLBT status as a law student or been involved in a leadership role at their college GLBT organization, and the entity might provide a reference. That’s something you’d normally put on a resumé, but frequently that’s a concern if they don’t know whether the firm is going to discriminate.”

These challenges are compounded by the fact that many firms simply don’t discuss GLBT issues, making it difficult for these attorneys to know whether the firm believes it’s honoring their privacy or it simply wants the issue to go away.

“Firm management who may feel they’re being appropriately respectful of the privacy of gay lawyers by not asking them personal questions such as ‘Do you want to bring your domestic partner to this client dinner?’ are instead sending a signal that GLBT lawyers are supposed to be closeted, that the families [of heterosexual lawyers] have value, and the gay lawyers are supposed to just be lawyers,” says Kelly Dermody, a partner at Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein in San Francisco. “If the leadership never uses the terms gay, lesbian or GLBT, or if the firm is completely silent, there’s a certain message being sent.”

Legal employers don’t hear many complaints from GLBT lawyers. Silence, however, isn’t necessarily consent. For its 2006 report, Challenges to Employment and the Practice of Law Facing Attorneys from Diverse Backgrounds, the State Bar of California surveyed lawyers who are female, 40 or older, GLBT or racial minorities. It found that while all groups experienced discrimination, 52 percent of minority attorneys reported that discrimination to their supervisor, as did 51 percent of female lawyers and 40 percent of older lawyers. However, none of the GLBT lawyers reported the mistreatment.

Many firms also don’t publish GLBT-specific information on their websites, whether it’s identifying openly gay attorneys, including their work in the GLBT community in staff bios, or directly referring to sexual orientation issues in the firm’s diversity materials.

Nor do they divulge GLBT data to NALP—the Association for Legal Career Professionals, which in 1996 began asking employers to report the number of openly gay lawyers in their firms or offices. By 2009, only 47 percent of participants in NALP’s annual survey reported at least one openly gay attorney.

The majority of firms reported zero GLBT attorneys, but NALP cautions that that figure may not actually mean the firm had none. Because of NALP’s reporting system, zero could also mean data wasn’t collected by the firm or is unknown.

NALP’s data is consistent with diversity consultant Arin Reeves’ findings that legal employers are less comfortable addressing gay issues than other diversity matters such as race and gender.

“I started my firm in 1999 and I’ve seen legal employers get much better over the last 10 years,” says the president of the Athens Group in Chicago. “When I say better, I’m referring to how bad it was 10 years ago compared to the comfort level with other diversity issues. But the level of comfort with GLBT issues is still definitely far below the level of comfort with race and gender.”

“A lot of law firms try to use the justification that it’s not that they’re uncomfortable” with GLBT issues, reports Reeves. “I hear more people saying, ‘It doesn’t really affect a lot of people. We’re focusing on other issues that affect more people.’ ”

Whatever the reason for many firms’ palpable silence, the result is that gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender lawyers must use detective-like skills to root out whether potential employers are GLBT friendly.

“Increasingly, the big firms are multistate,” Stewart explains. “For some, maybe their San Francisco office is quietly gay friendly, yet their national office isn’t. There are underground networks, but if the firm is at a management level squeamish and thinks there’s something wrong about being direct about the issue, it makes the information difficult to get.”

Is Diversity Dead?

Though many legal employers decline to address GLBT issues, a growing number are joining the inclusiveness movement. The driving force isn’t a feel-good or do-good political correctness: Legal employers say they are pushing toward a culture of inclusiveness to ensure that GLBT and other minority employees have a fair shot at professional growth and advancement—and at generating better work product for clients.

The difference between diversity and inclusiveness isn’t semantic. It marks a significant change in the approach toward GLBT and other minority employees.

“Diversity sometimes ends up being a demographic analysis of how many of each category of minority employee we have,” says Todd Young, a partner at Hinshaw & Culbertson in Chicago. “That’s a goal. Inclusiveness goes a step further.

“How do we make sure those diverse people all have the same chance to thrive and succeed? For diversity, you’d hire a dozen people and hope all of them stick—period. For inclusiveness, you have to think more long term about those lawyers’ relationship with the firm.”

Former ABA President Robert J. Grey Jr. says inclusiveness pierces the soul and spirit of a legal organization.

“Is [the firm] really working to achieve this level of inclusiveness that we all seek to achieve, or are we doing it more superficially?” asks Grey, a partner at Hunton & Williams in Richmond, Va. Grey is interim executive director of the Leadership Council on Legal Diversity, an organization of chief legal officers and law firm managing partners working to improve diversity in the profession.

“We may have GLBT, women and African-American lawyers,” he says. “But are they part of the team that deals with the fundamental issues that go to the survivability and sustainability of an organization? Are they part of the teams that do the most important work for the clients?

“It’s one thing to be in an organization. It’s another to say we’re participating in the critical activities of the organization. The first is diversity; the second is inclusiveness.”

Implicit in the push for inclusiveness is the idea that diversity has failed if its goal was to create a level playing field that allowed minority lawyers to advance into leadership roles. According to the NALP Foundation’s 2008 Update on Associate Attrition, by their fourth year of practice, 75 percent of diverse attorneys have left their law firm, compared to 66 percent of nondiverse attorneys. By the fifth year, 85 percent of diverse lawyers have left, compared to 76 percent of nondiverse attorneys.

“Diverse attorneys come into the organization and discover that many aspects of the dominant culture marginalize them and push them to the sidelines,” says Nalty. “They don’t feel genuinely included, that they have a seat at the table and receive the same opportunities, so they leave.”

Legal employers also expect that inclusiveness will generate more creative work product, which clients are demanding. “A lot of the energy from the movement of diversity and inclusiveness has come from clients,” Grey says. “This notion of inclusiveness has more traction because our differences give us more options to solve problems instead of just one path to a solution. We now have three or four paths because we’re incorporating these differences to achieve a common goal.”

Creating Change

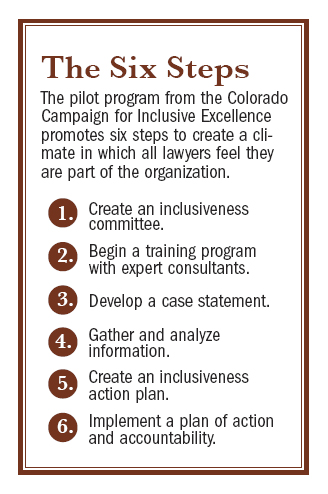

Among the leaders in the inclusiveness movement is Nalty’s Colorado Campaign for Inclusive Excellence. In 2008 the campaign created a pilot program with 10 legal employers, including five small-to-large regional law firms, the Denver office of a national firm, two government law offices and two corporate legal departments. The program is testing a six-step process to create a culture of inclusiveness for GLBT and other minority lawyers.

The program has prompted participants to rethink their own behavior. “It challenged us to think more broadly about diversity issues,” says Rich Baer, chief administrative officer and general counsel at Qwest Communications International Inc. in Denver. “We’ve come to realize that lawyers really thrive in an environment of inclusion—and this doesn’t just mean diverse lawyers, but all lawyers. The best environment is where their advice is welcome and listened to, and that really only occurs if the environment is truly inclusive, where lawyers are being welcomed into the fabric of the company.

“That helped us looking at our own attitudes,” Baer admits. “Do we welcome all different views, or can we be dismissive? I’m from Brooklyn, N.Y., and I prosecuted homicide cases. I’m the first one who can too quickly form a view and not listen to others’ views. That’s not an inclusive environment.”

The pilot is also helping expose hidden barriers to retention. “A lot of things happen within a legal organization that people don’t realize and aren’t doing intentionally,” Nalty says. “For example, I have a new bookkeeper who reminds me of my sister. I instantly felt a bond with her. If I were at a law firm, I’d be looking for ways to work with her. When I said that to a general counsel, it was a huge ‘aha moment’ for him.

“When lawyers think about diversity and exclusiveness, they say, ‘We’re not intentionally discriminating against people.’ But there’s so much they do based on their preference for people and working with people in their comfort zone. That’s how exclusionary practices happen.”

Another hidden barrier is evaluations. “Majority attorneys are sometimes worried about how their feedback is going to be perceived when they review diverse attorneys,” Nalty says. “They may unconsciously hold back and take too much care in how they word feedback. When you pull your punches and give soft evaluations, people don’t hear about things they need to be successful.”

Though the program focuses on all diverse employees, pilot program member Michael Connelly, vice president and general counsel at Xcel Energy Inc. in Minneapolis, says GLBT issues present unique challenges.

“Collecting statistics is the biggest challenge,” he says. “Firms will say they don’t ask for that information, and I say, ‘I’d like you to.’ ”

There’s also discrimination against GLBT attorneys that’s permitted in many workplaces. “There’s still acceptance of the excuse that [attorneys’ being open about their orientation] will make clients uncomfortable,” Connelly says. “If you put a picture of an attorney of color in your office, what if that makes your clients uncomfortable? You’re still going to do it, right?

“There’s also discrimination that’s permitted in things people say to members of the GLBT community that they’d never say to attorneys in another community,” he says. “For example, ‘I don’t agree with your lifestyle. What you’re doing is wrong based on my religious beliefs.’ That’s nice, but, one, it’s not relevant to people’s performance and, two, we have policies against discrimination.”

Pilot program members have made missteps. “One organization sent its survey out without giving it as much thought as it should have,” Nalty says. “The survey didn’t come from upper management and the organization hadn’t let people know why it was doing the survey. Another organization learned from that and did it differently. It had a higher response rate and less pushback.”

Employees in the pilot organizations view the programs positively. “Generally speaking, it’s seen as an important effort within the office,” says David Fine, Denver’s city attorney. “We have a waiting list to be on our inclusiveness committee.”

Complaints have filtered back to Fine, however. “Being the city attorney, I haven’t heard it directly. What I’ve heard is ‘It’s political correctness’ or ‘We’ve had these efforts before, and they come and go.’ You’ll have skeptics, but I’d like them to be on the committee because otherwise you’re preaching to the choir.”

Among the skeptics are some white males, Fine says, “but inclusiveness means every person in the organization needs to be invested and empowered. Unlike diversity efforts, inclusiveness efforts take into account people’s values regardless of their external features. So any program should make those white males feel comfortable, too. To be effective, it has to.”

It’s too early to talk about the pilot program’s results, and participants concede success will be hard to measure.

“We’re at the very early stages of whether I can be in a position to hold anyone accountable for results,” says Connelly. “Having said that, when I meet with firms, I can see whether they’re raising the issue or whether I am. You can tell when someone’s understanding the issue and taking active steps, and you can tell when someone’s begrudgingly doing it because I’m telling them it’s important.

“You also want to look at the issue over time. We and a lot of companies are abysmal at results, but we’re going to keep trying until we get better results.”

The lessons learned from the pilot program in Denver will be used to revise its how-to manual for employers, Beyond Diversity: Inclusiveness in the Legal Workplace, which is expected to be available on the Internet this spring.

Moving Ahead

Rich Baer

Photo by John Johnston

Some legal employers aren’t waiting for the outcome of the Denver program to build inclusiveness at their workplaces. They’re actively pursuing a perfect score on the Human Rights Campaign’s annual Corporate Equality Index, which rates businesses on a scale from 0 to 100 percent for their treatment of GLBT workers.

In 2006, 12 law firms scored 100 percent. This year, 88 of the 127 firms that submitted data achieved a perfect score, including Hinshaw & Culbertson, Jenner & Block, and Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner.

Firms are also increasingly offering domestic partner benefits for GLBT employees, creating affinity groups supported and funded by firm leadership that allow employees to work on workplace and community issues important to the GLBT community, and actively supporting pro bono work on GLBT causes.

The leadership at Arnold & Porter, which also received a 100 percent rating on the Corporate Equality Index, thinks it is sending an important message through its decisions about who leads the firm. “GLBT partners are considered for leadership in the same way other attorneys are, and a number of gay attorneys over the years have held significant leadership positions,” says Washington, D.C.-based partner Paul Pompeo. “Where you have gay people in positions of leadership and it’s no big deal, that sends a message to both lawyers and staff as to the leadership’s recognition of the value of GLBT attorneys.”

Yet even GLBT-inclusive firms are struggling to address sticky issues. Many legal employers offer domestic partner benefits, yet few have increased the pay of GLBT attorneys to compensate for the disparity in treatment under federal tax laws between opposite-sex and same-sex benefits. Because same-sex marriage isn’t legal under federal law, the IRS treats benefits offered to same-sex partners as additional income, increasing the tax burden on the employees whose benefits cover their partners.

“It can be significant, and it doesn’t happen if you’re heterosexual,” says Dermody, whose firm has boosted the pay of employees caught in the tax bind. Arnold & Porter is considering making the change, according to firm spokeswoman Patricia O’Connell.

Firms also struggle with whether and how to ask GLBT attorneys to come forward and be counted. “A lot of firms ask, but they ask in a way—and their overall environment operates in a way—that people are scared,” says diversity consultant Reeves. She advises firms to lay the groundwork before asking GLBT attorneys to self-identify.

“First, communicate that GLBT issues are part of your anti-discrimination policy and something you’re committed to, but not just in a onetime e-mail,” she says. “If you don’t create the environment that says to people that any answer they give is a good answer, you’re going to skew the answers.”

Some firms are stressing that clients have requested GLBT data. “A number of large firms have started sending an e-mail blast to attorneys stating, ‘As part of our marketing efforts with our clients, if you’d like to self-identify as GLBT, please let us know. We support your decision,’ ” Dermody says. “It’s a clever and useful way to let GLBT lawyers know [that the firm understands] them, and that there’s an objective to knowing that information.”

L. Allyn Dixon Jr., an attorney at Dickinson, Mackaman, Tyler & Hagen in Des Moines, Iowa, has simple advice for employers unsure how to respectfully address GLBT issues: “The best approach is to treat GLBT attorneys as you treat everyone else,” he says. “You can’t force people out, but if somebody sticks a toe out, ask if there’s anything they’d like you to be doing to support their community.

“I’ve felt completely embraced and welcomed here,” Dixon says. “I feel like at this point in my career, I need to be giving back to my community, and my firm lets me do that.

“That makes my experience here a good one and my overall productivity better.”

Sidebar

The Forgotten T

The T in GLBT represents transgender individuals, a minority within the minority facing a kind of discrimination and disrespect that few, even within the gay and lesbian community, have considered.

M. Dru Levasseur faced challenges few other students encounter when he transitioned during law school. “People met me as female and under a different name,” says the 2006 graduate of Western New England College School of Law, “and there was no way for me to have a different way to come out.”

One of Levasseur’s biggest challenges was how to address his gender identity during the hiring process.

“A lot of my jobs outed me, so I said on my cover letter that I was a transgender attorney,” he says. “During an interview, one person asked, ‘Do you really think it’s a good idea to tell people you’re a transgender attorney?’ I said, ‘Yes, I do. In fact, I think it’s a strength that I’ve gone through the challenge of transitioning, and I’m still a great attorney and have achieved in spite of all the extra stress.” He got a job offer there.

Levasseur also faced outright discrimination. “I was on a second interview [at a Northeastern office of a national firm], and the partner asked, ‘What’s transgender?’ ” he recounts. “I started telling him, and he interrupted and said, ‘There are no gay people at the firm. If you wanted to start a gay group, you’d be the only one in it.’ ”

Limited Prospects

Levasseur, now a staff attorney at the Transgender Legal Defense & Education Fund in New York City, believes his candor about being a transgender attorney dented his job prospects. “I felt like my choice to be an out transgender attorney limited my options,” he says. “Diversity is coming around and it’s a hot topic, but being a transgender attorney is still an issue.”

Shannon Minter

Photo by Trish Tunney

Shannon Minter transitioned in the mid-1990s after serving for three years as a staff attorney at the National Center for Lesbian Rights in San Francisco. Today he’s the organization’s legal director. Last March, he argued to overturn California’s Proposition 8, which bans same-sex marriage, before the state’s supreme court.

“I’ve never tried to get hired by a firm, but I’ve had some offers along the way,” Minter says. “But that happened only after people had a chance to work with me and get to know me over a period of time.

“I think we’re still very much at the phase where most corporations and law firms would simply not consider a transgender candidate if they knew,” Minter says. “People have a lot of biases and stereotypes, and they think it’s very weird, strange and off-putting. That’s a shame.”

Arin Reeves, an inclusiveness consultant and president of the Athens Group in Chicago, agrees. “Even though a lot of organizations are saying GLBT, what they really mean is L and G,” she says.

“When you ask firms, ‘Have you put anti-discrimination practices in place that would really allow you to focus on discrimination against transgender attorneys?’ you’ll find most employers haven’t done that. There’s some movement forward with gay and lesbian issues, but there’s still a lot of work to be done with transgender issues.”

Minter adds that “many gay, lesbian and bisexual folks in the everyday work world who aren’t deeply involved in political advocacy are uncomfortable with transgender people.

“It’s particularly painful. There’s an expectation that if someone is lesbian or gay, they’ve experienced discrimination or been treated differently, and you’d expect them to be naturally sympathetic. That’s sometimes true, but not always.”

G.M. Filisko is a lawyer and freelance journalist in Chicago.