Journalism & Justice: Did Innocence Project Student Reporters Get Too Close to Lawyers?

Monica Kim was thrilled to gain a spot in Protess’ class and taken aback to learn he would not be leading it. “I was under the impression that I would be working with Professor Protess. It was kind of a surprise for everyone in the class.” Photo by Len Irish.

Last spring Monica Kim, a Northwestern University journalism student, ventured into some of Chicago’s roughest and most impoverished neighborhoods as part of a class project to investigate whether a man was wrongfully convicted of murder.

Kim was a little nervous at first as she knocked on doors to locate witnesses on the city’s West Side, but she pressed on because she believed she was doing important work. That work began to pay off when, one morning two blocks from where the murder took place, Kim and classmate Taylor Soppe found a woman who witnessed the crime.

“We just told her that we were students and that we were investigating this case and she said, ‘I’ll tell you all about it,’ ” Kim recalls.

In the span of 10 weeks, Kim and her classmates, along with the help of a private investigator, compiled dozens of interviews and thousands of documents that suggested Donald Watkins could not have committed the 2007 shotgun murder of Alfred Curry. Their findings were posted on a university website in June along with the documents and transcripts they acquired, much of them through Freedom of Information Act requests.

It was another shining moment for the Medill Innocence Project, the famed Northwestern program that has helped exonerate 11 wrongfully convicted people and was, by many accounts, instrumental in prompting Illinois’ then-Gov. George Ryan to suspend executions and clear the state’s death row.

The difference for Kim and her classmates was that the class was not led by its highly regarded founder, David Protess. Protess was forced into a leave of absence—and has since retired from the university—after university officials and prosecutors questioned his integrity and investigative techniques. Another professor took over the course, while Protess continues teaching at an off-campus location.

The case has exposed the potential dangers of mixing student journalism and legal advocacy, and raised questions about what role, if any, investigative journalists should have in assisting lawyers seeking to correct alleged injustices.

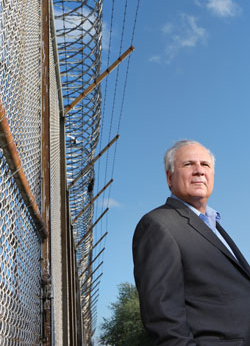

David Protess, who founded the Medill Innocence Project in 1999, retired last year after prosecutors and university officials questioned his investigative techniques. “There is no one way to run a journalism innocence project,” he says of the class, which helped free 11 wrongfully convicted people. Photo by Katrina Wittkamp.

SHARED INFORMATION

The controversy leading to Protess’ departure was ignited in May 2009 after lawyers for Northwestern University School of Law’s Center on Wrongful Convictions, a separate entity from the Medill Innocence Project, filed a petition seeking the release of Anthony McKinney, convicted in 1981 of killing a security guard. Protess’ students investigated the case and shared their findings with the center’s lawyers.

But in response to the petition, Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez subpoenaed notes and records from the class, including student memos, academic transcripts and private emails generated during their investigation. Alvarez argued that all such material was subject to discovery.

At first university officials led by John Lavine—dean of the Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications—backed Protess. They called the subpoena overreaching and asserted that student journalists are protected by the state’s reporter shield law. Alvarez countered that the students acted as investigators for McKinney’s legal team and not as reporters, and that any information they shared with the legal team was subject to the same rules of discovery as those for all lawyers.

Alvarez also accused Protess of misleading prosecutors about what information he shared and didn’t share with McKinney’s legal team. The state’s attorney claimed in later court filings that his students used questionable tactics: that they lied about their identities, flirted with potential witnesses and sometimes even paid them.

The university’s support of Protess began to crumble when administrators discovered the professor withheld information from the university and its lawyers about what he shared with McKinney’s lawyers. Sidley Austin withdrew from legally representing the university, and Northwestern hired Jenner & Block to investigate further, including combing computer hard drives.

“The review uncovered numerous examples of Protess knowingly making false and misleading statements to the dean, to university attorneys and to others,” said Alan Cubbage, Northwestern’s vice president for university relations, in a statement. The university turned over relevant documents, including redacted emails, officials thought fell under the rules of discovery.

In early September, Cook County Criminal Court Judge Diane Cannon sided with the prosecutors, accepting the argument that student reporting is protected under Illinois law, but ruling that the students were acting as private investigators and not student journalists in the McKinney case.

Cook County State’s Attorney Anita Alvarez responded to an NU petition seeking the release of Anthony McKinney by subpoenaing notes and records from Protess’ class. AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast

Cubbage responded: “We are pleased that Judge Cannon recognized the applicability of the Illinois Reporter’s Privilege Act to student journalists, such as those involved in the Medill Innocence Project. We respectfully disagree with Judge Cannon’s application of the law to the facts in this case, but we have decided not to appeal the court’s decision. … The university will provide the remaining materials that were subpoenaed.”

In a vociferously argued essay in the Huffington Post, Protess maintained that he and his students did nothing wrong.

“I have no problem with sharing information with the state’s attorney’s office,” Protess later told the ABA Journal. “Prosecutors hold the keys to the freedom of innocent prisoners, and I have a long history of cooperating with them. How do you think we were able to help free so many innocents? Indeed, most of our sources wanted us to cooperate with prosecutors to correct an injustice.

“The problem I had with prosecutors in this case was their demand for private information generated by the students. Virtually everything that was tendered had no bearing on McKinney’s innocence or guilt. It was totally irrelevant to the sole question before the judge: Was Anthony McKinney wrongfully convicted and entitled to relief?”

As for the university’s decision to end litigation, Protess says, “I believe the university would have prevailed on appeal, but I’m pleased that they instead decided to turn over the remaining documents. An appeal would have meant another year’s delay in the proceedings. Now Anthony McKinney will finally get a hearing on the evidence of his innocence.

“If I had to do it all over again,” Protess says, “the only change I would have made is hiring my own lawyer, someone who would represent the interests of my students and innocence project. Counsel in this case cared primarily about his paying client, the university, and I should have acted on the ensuing conflicts far sooner than I did.”

NOT FOR JOURNALISTS?

Writing last April in the online journal Minding the Campus, a publication of the conservative Manhattan Institute, contributing editor Charlotte Allen argued that journalism schools “have no business operating innocence projects.”

“Innocence projects are almost always run by law schools,” Allen says when interviewed. “Law students know what they’re getting into. Things get much murkier when you get journalism students involved.”

Law school innocence projects have been springing up around the country for the past two decades, with more than 60 such programs now operating in the U.S. However, there are just a handful of journalism innocence projects.

One of those is the Innocence Institute of Point Park University in Pittsburgh, led by award-winning investigative journalist Bill Moushey. Like the Medill Innocence Project, Moushey’s institute is dedicated solely to investigating possible wrongful convictions.

Bill Moushey of Point Park University was inspired by Protess’ work. “I saw what Protess was doing and said I’d like to try something like that.” AP Photo/Andrew Weier

“I saw what Protess was doing and said I’d like to try something like that up here,” Moushey says. “We’re a very small operation. We are not an activist organization but a journalistic organization.”

As such, the program has no relationship, formal or informal, with any law school innocence projects. Moushey says he’s careful to keep students from working too closely with lawyers, even as sources.

“We publish everything we do. We don’t use outside investigators either,” he says. “The whole point of the program is to teach the kids how to do this stuff. I don’t want to venture away from journalism in any way, shape or form.”

Once an investigation is complete, the Point Park students publish their work in a glossy magazine called Justice. The cover story of one issue offers evidence that a man convicted of starting a fire in which three firefighters died is innocent.

Moushey says if the student investigation draws the attention of lawyers who want to take up the case, all the better. But student involvement ends there. “In light of the Northwestern situation, we’re not giving anyone anything in the future,” he says.

Brandeis University in Waltham, Mass., has a program called the Justice Brandeis Innocence Project, part of the Schuster Institute for Investigative Journalism. Its mission statement says it “was established to make a contribution to resolving the untenable ethical, civil and human rights issues created by wrongful convictions.”

Brandeis, Point Park and Medill are the only journalism programs that are members of the Innocence Network. Keith Findley—the network’s board president, a University of Wisconsin law professor and co-director of the Wisconsin Innocence Project—says board members had been concerned about addressing some of the legal and ethical implications of journalism projects long before the Medill controversy surfaced.

“Journalism projects are different because they don’t represent clients and are not subject to the same legal and ethical guideposts as lawyers,” Findley says. “We’re looking to determine what kinds of ethical considerations we want to use as a condition of membership.”

Asked whether innocence projects should be operated with a direct connection to a law school or complete separation from lawyers, Protess responds: “This question reflects a misunderstanding about the structure and operation of the [Medill] class. Our reporting was done independently of the law school. In fact, as my Huffington Post piece points out, McKinney did not even have a lawyer during the first two years of our investigation, when virtually every major finding was unearthed by my students. When the legal team became involved in 2005-06, they did not participate in a single interview.

“More generally,” Protess says, “the question reflects a misunderstanding about the functioning of journalists, student or otherwise. Every journalist who writes about the legal system is dependent on information provided by lawyers, so ‘complete separation’ does not exist. Criminal courts reporters, for example, regularly get leaks from prosecutors or defense attorneys.

“Like investigative reporters who cover the justice system, my students and I cultivate relationships with lawyers on both sides. On a handful of occasions in the McKinney investigation, we obtained affidavits from witnesses that were shared with the defense team, but those affidavits also were posted on our website and copies were later given to prosecutors.

“But there is no one way to run a journalism innocence project,” Protess adds. “Please keep something in mind that has been ignored in the controversy: The reporting is being done by college students as part of a learning experience. Exposing students directly to the legal procedures for righting wrongful convictions is integral to their education about both journalism and the law.”

Alan Cubbage, vice president for university relations, said in a statement that NU disagrees with Judge Diane Cannon that students acted as private investigators, but it will not appeal the court’s decision. Northwestern is providing the remaining subpoenaed materials. Photo by Katrina Wittkamp.

STUDENTS WANT MORE

While journalism school innocence projects and law school innocence projects share the same interest in correcting an injustice, some journalism students have found that writing stories is not enough.

One of Protess’ former students, Shawn Armbrust, was an aspiring journalist in the Medill program who realized that legal advocacy was a better way to pursue her passion for righting wrongful convictions. She’s now director of the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project at American University’s Washington College of Law.

Armbrust felt right at home in Protess’ class, which inspired her to pursue her legal career.

“I loved the subject matter, and I love reading legal documents. I liked the legal aspect of the work,” she says. “I didn’t think I could do what I wanted as a journalist, but could do it as a legal advocate.”

After graduating in 1999, she went to work for the Center on Wrongful Convictions as a case intake coordinator. Two years later, she went to law school at Georgetown University, graduating magna cum laude.

Armbrust still carries her experience with Protess’ class. “I learned a lot there. I had never done investigations before,” she says. “I learned how to talk to witnesses. I learned from David to treat your witnesses like people. I learned you should never take anything for granted while doing a case.”

In her current role, Armbrust says, she does not work often with journalists. “The relationship between journalism projects and innocence projects is complicated,” she says. “You have to be careful.”

Kim heard about Medill’s reputation while she was still in high school in Oshkosh, Wis. Once she got in as an undergrad, students were talking about Protess’ investigative journalism class and how they helped free wrongfully convicted prisoners.

“I remember being a freshman and telling myself you have to take that class. It was so built up,” she says.

Admission was competitive. Kim applied when she was a senior and had to answer questions about her journalism experience and desire to take the class. She emailed her responses to Protess and was thrilled to learn she got in. But right before classes started for the spring quarter, she learned Protess would not be teaching.

“I was under the impression that I would be working with Professor Protess,” she says. “It was kind of a surprise for everyone in the class.”

Alec Klein, a former investigative reporter, took over the project and instituted a policy barring students from sharing info with attorneys. “When we investigate a story,” he says, “we are trying to find the truth, whatever that truth is.” Photo by Katrina Wittkamp.

In his place was Alec Klein, a professor, former investigative reporter for the Washington Post and Wall Street Journal, and a New York Times best-selling author. Klein stepped into a difficult situation, but he led his class with the kind of enthusiasm and drive for which his predecessor was so well-known.

Klein made clear from the beginning that his students were practicing journalism and were not legal advocates or crusaders. If their investigation turned up enough solid information, they would publish their findings. “Alec made it extremely clear that we were journalists and not lawyers,” Kim says.

Further, Klein instituted a policy on what the students would do with any information they gathered during their investigation or produced for the class: They would not share it with attorneys.

“We gather information. We write it. We publish it. I want to be fully transparent about the process,” Klein says. “We are not advocates, and I make that crystal clear to my students. When we investigate a story, we are trying to find the truth, whatever that truth is.”

Klein also decided that neither he nor the students would reach out to Northwestern’s Center on Wrongful Convictions about their investigations, something Protess did routinely under the old model because of his long-standing relationship with the center.

But Klein emphasizes that his policies were not created as a result of, or meant as criticism of, his predecessor, and that he does not sit in judgment of Protess, whose work he admires.

“If you are investigating miscarriages of justice, you are doing the public good,” he says.

Rob Warden, executive director of Northwestern’s Center on Wrongful Convictions, says the Anthony McKinney case is “the first time material of this sort has been subpoenaed.” Warden adds that “the sad thing about all of this” is that “an innocent man… is being punished mercilessly” by the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office. Photo by Katrina Wittkamp.

SEEKING INNOCENCE

Protess, a longtime investigative reporter who had taught journalism at Northwestern since 1981, founded the Medill Innocence Project in 1999 after several high-profile cases in which he and his students helped exonerate innocent men. In its original conception, the project was part of Northwestern law school’s Center on Wrongful Convictions, which Protess co-founded earlier the same year.

Rob Warden, executive director of the center, was and remains good friends with Protess. They worked together as investigative reporters when Warden was editor and publisher of Chicago Lawyer magazine. Warden built a reputation as a muckraker, and together he and Protess investigated wrongful convictions, two of which became the subjects of books they co-authored.

They both liked the idea of creating a program dedicated to investigating wrongful convictions, but Warden says he thought it wise to separate the law school and journalism school programs. “There are very different rules governing lawyer conduct and the conduct of journalists,” he says. “You really can’t have journalists working as investigators for counsel.”

Student journalists working on their own would be free to interview whomever they wanted and not be bound by discovery rules or other rules that govern lawyers. “We decided early on that it was best we go our separate ways for that particular reason,” Warden says.

Protess and his class conducted their own investigations and often shared their findings with the center. “We then conducted our own investigations and developed our own evidence,” Warden says.

Such was the case with the McKinney investigation, Warden says, though he does not remember specifically what Protess and his class shared with the center. “Obviously they turned over a lot of stuff,” he says. “This is the first time material of this sort has been subpoenaed.”

Emails discovered by the university and turned over to the state’s attorney’s office show that Protess clearly understood that sharing information with attorneys could open the door to their notes being subject to discovery.

In one email to his students about a pending meeting with McKinney’s attorneys, Protess instructed them to bring certain documents and transcripts but warned: “Please do not bring any copies of your memoranda, as I don’t want our ‘internal’ communications to become potentially discoverable to the state.”

But it was a later email that caused Protess trouble, one that appeared to be altered after he and his students were subpoenaed. It was a copy of a 2007 email to his assistant about what was shared with McKinney’s lawyers. The copy Protess sent the university said: “My position about memos, as you know, is that we don’t keep copies.”

But the original, the university found, stated: “My position about memos, as you know, is that we share everything with the legal team, and don’t keep copies.” Protess told the Chicago Tribune that he altered the email because the statement was written in a casual tone and not meant to be taken literally.

STILL LOOKING

For Kim and her classmates who investigated the Watkins conviction, their work is done. According to their website, Watkins now has a public defender, but a post-conviction petition Watkins filed himself may make it difficult to use some or all of the information the students gathered.

Kim moved to New York City after graduating in June and is an assistant editor at Condé Nast Traveler magazine. She hopes to someday do the kind of investigative journalism she learned in her Medill class. “It’s something that will remain with me,” she says. “It was such an amazing experience.”

Warden read about the Watkins investigation on the Medill website but has had no contact with the students or with Klein. As with other cases, Warden says the center may evaluate it on its merits. That’s the way it should be, he says.

“The way to run a journalism innocence project is to have the students report on the case, post it on a website, post documents and—if they find lawyers who are interested—to provide what they wish but be mindful that whatever they provide is subject to discovery,” Warden says. “It will be clear and simple that way.”

Klein is leading his latest class into another investigative project. He plans to carry on in the spirit in which Protess ran the program. “The Medill Innocence Project is a strong brand name and has a history and a tradition,” Klein says. “I think the idea behind it is a powerful one—that if you uncover information that a person is wrongfully convicted, you’ve made a significant impact.”

Warden says one important point should not be lost. “The sad thing about all of this is that Anthony McKinney is an innocent man and he is being punished mercilessly by the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office.”

Protess remains passionate about his work as an investigative journalist. Since leaving Medill, he has started the Chicago Innocence Project, a nonprofit much like the Medill Innocence Project. Six students from Medill were among the first to join with students from other Chicago-area colleges in the new project; they are publishing their work on the project’s website.

Looking back at the series of incidents, Protess says, “It was a perfect storm. I hope that innocence projects do not alter what they do because of our experience.”

Death row inmate Anthony Porter lifts Protess with a hug after being released from prison in February 1999 in Chicago. AP Photo/Beth A. Keiser

Corrected on Dec. 29 to identify Alec Klein as a tenured professor at Northwestern University. The ABA Journal regrets the error.

Correction

Corrected on Dec. 29 to identify Alec Klein as a tenured professor at Northwestern University. The ABA Journal regrets the error.Kevin Davis is a freelance journalist based in Chicago and the author of Defending the Damned and The Wrong Man. ABA Journal legal affairs writer Rachel M. Zahorsky contributed to this report.