James Brosnahan

James Brosnahan

Photo by Mel Lindstrom

James Brosnahan has tried more than 140 cases to a verdict. He’s prosecuted murderers and the secretary of defense. He’s defended the chair of Hewlett-Packard and the man known as the “American Taliban.”

But when it comes to weird moments in court, nothing tops an experience in Reno, Nev., a few years ago.

Brosnahan was defending a man in a civil tax recuperation case in federal court.

“I was sitting at the defense table, making notes for my closing argument, when I suddenly hear this scream,” says Brosnahan. “I look over and my client has opposing counsel by the throat.”

Brosnahan rushed over to pull his client off the lawyer. The federal judge hit the panic button under the bench, causing U.S. marshals to storm into the courtroom, weapons drawn.

“The defendant is trying to kill the tax attorney,” the judge yelled out.

The marshal paused, holstered his gun and, in a calm voice, responded, “Judge, that’s only a misdemeanor.”

“We won the case, but my client still went to jail for six months for attacking the tax attorney,” says Brosnahan.

Brosnahan turned 75 in January, but he has no plans to slow down. He has four jury trials and two nonjury trials already scheduled for this year.

“My standard for taking a case is extremely low,” he says. “But nothing compares to the electricity of an actual trial, and it is magnified when it is a jury trial.”

A senior partner at Morrison & Foerster in San Francisco, Brosnahan has received about every honor the legal profession hands out. The American Inns of Court honored him with its 2007 Lewis F. Powell Jr. Award for Professionalism and Ethics. The American Board of Trial Advocates and the American College of Trial Lawyers named him lawyer of the year in separate years. His online bio is 18 pages long, listing all of his major court victories, honors and published articles.

Brosnahan says his decision to try all kinds of cases—civil and criminal—has allowed him and trial lawyers of his generation to gain the courtroom experiences that following generations have not had.

“The emphasis on specialization of practices is not all good,” he says. “I strongly encourage today’s young litigators to take on one or two criminal cases every year. It will make your civil trial practice so much better.”

EARLY DAYS IN THE DESERT

Brosnahan started his legal career as a prosecutor in the U.S. attorney’s office in Phoenix. He remembers his first jury trial as if it were yesterday. The date, he says without hesitating, was April 10, 1961. The charge was murder. The defendant, who was a member of the Pima tribe, had repeatedly stabbed the victim, a member of the Apache tribe.

The murder took place in Bapchule, a small Arizona village that consisted of five huts. The victim lived in one hut and the defendant lived in another. During jury selection, a prospective juror announced that he also lived in one of those huts in Bapchule but claimed he didn’t know the defendant.

“I had no idea what I was doing,” Brosnahan says. “But I knew that there was no way this juror didn’t know the defendant. That’s when I first realized that sometimes jurors lie.”

Brosnahan used one of his peremptory strikes to remove that juror and went on to win a first-degree murder conviction against the defendant.

“The great thing about jury trials is that there are always surprises,” he says.

Brosnahan points to a trial he conducted in Santa Clara, Calif., a few years ago. He asked jurors in the venire whether anyone in the group was a party to a pending case in court. A woman seated in the second row raised her hand and said she was a defendant in a case.

“What kind of case—civil or criminal?” Brosnahan inquired.

“A criminal case,” she responded.

“What is the charge against you?” he asked.

“A murder case,” the woman replied.

“All at once, the jurors sitting beside her slowly started moving away,” he says. “I didn’t need to use a peremptory on her.”

In 1989, Brosnahan represented Steve Psinakis, a Greek-American businessman charged with illegally transporting explosive materials. Psinakis had been involved in the overthrow of Ferdinand Marcos. Philippine President Corazon Aquino pressured the U.S. government to drop its case. And witnesses at trial included the Philippine secretary of state.

Twenty-seven federal agents had raided Psinakis’ home, pointed guns right against his face, physically threatened him and drugged his dog.

“The judge didn’t react at all to what the agents did to my client, but when he heard about the treatment to the dog, he was outraged,” says Brosnahan. “That’s when we learned the judge was a dog lover.”

Key evidence in the case was the photographs the agents took when they raided the house, showing a bowl with the makings of a bomb—wires, glue, scissors and other items. However, Brosnahan discovered other photos taken by the agents that showed the same bowl, but without glue and wires.

Under oath, the defense attorney finally got an FBI agent to admit that he had staged the photo, completely undermining the government’s case. The judge was already upset at the government about the dog, he says, and this fabrication of evidence pushed him over the edge. In the end, Psinakis was acquitted.

Brosnahan says he gets a lot of “last-minute clients” who are represented by other lawyers throughout the litigation process. He says he’s been hired as little as three weeks before the start of a trial.

“These clients wake up one morning and realize, holy cow, they are going to trial and they need someone who has experience actually trying cases,” he says. “I actually enjoy those situations because it forces me to zero in on what matters in a case. There are not 25 or 30 important witnesses in any case. Instead, there are only two or three who truly matter.”

In 1991, Iran-Contra independent counsel Lawrence Walsh lured Brosnahan temporarily back to the prosecution side to lead the trial team against Caspar Weinberger, who was the secretary of defense under President Ronald Reagan.

News made it to the FBI that Weinberger had taken and kept copious notes of Cabinet meetings at which the sale of arms for hostages was discussed. However, Weinberger told federal agents he had no such notes.

“The minute the FBI agents left his office, Weinberger pulled out his notebook and wrote that the FBI came seeking his notes and that he had lied about the existence of the notes,” says Brosnahan. “Weinberger was concerned that the notes would have led to Reagan’s impeachment, which I doubt. But he should have turned them over.”

Five days before the 1992 presidential election, Brosnahan secured a federal indictment against Weinberger, charging him with making false statements to Congress. The indictment included a handwritten note by Weinberger indicating that President George H.W. Bush knew more than he had claimed.

Republicans accused Brosnahan of playing politics with the justice system, causing Bush to lose his re-election bid to Bill Clinton.

“I was suddenly elevated from an infrequent contributor to Democratic politicians to being the mastermind behind the Democratic Party,” Brosnahan says.

On Dec. 16, during a closed hearing in federal court to review secret, classified evidence, Brosnahan said he noticed that Weinberger’s lawyer, prominent Washington, D.C., criminal defense attorney Bob Bennett, kept getting up and leaving the hearing.

The hearing ended with Bennett telling Brosnahan and the judge that he planned to subpoena President Bush to testify during the trial on Jan. 21—the day after Bush would leave office and thus could no longer claim presidential immunity.

“We had documented that Bush had given 218 different explanations of where he was during Iran-Contra, so we knew he didn’t want to testify,” Brosnahan says.

“Eight days later, on Christmas Eve, we received word from the White House that President Bush had issued full pardons for Weinberger and five others, thus ending any need to call the president as a witness in the case.”

FIGHTING THE TIDE OF PUBLIC DISAPPROVAL

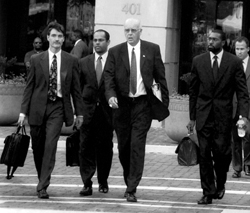

Click here to read more about this U.S. v. Lindh image.

Photo courtesy of James Brosnahan.

A decade later, Brosnahan would face the case of his life. He was watching the evening news when he heard about the arrest of American citizen John Walker Lindh, who had been captured on a battlefield in Afghanistan. Lindh was immediately labeled the “American Taliban.”

“[U.S. Attorney General John] Ashcroft went on national television to declare that John was evil, that he was a terrorist, and that he hated America,” says Brosnahan. “I told my wife that night that this kid is in a whole lot of trouble.”

The next day, Dec. 2, 2001, Brosnahan was home watching the San Francisco 49ers when his office message system notified him of a pending voice mail. The message was from Frank Lindh, the young man’s father, asking him to take on his son’s case.

“I told John’s parents that I am not a movement lawyer and that I represent individual clients, not movements,” he says. “I told them that if I ever got the feeling that I was being used for the purpose of a movement, that I was off the case.”

Brosnahan met with his partners at Morrison & Foerster to get their input. If his partners had advised against, he says, he wouldn’t have taken the case.

That being said, “I was absolutely sure that this case could kill my career,” he says.

Brosnahan took the case on Dec. 3 and immediately fired off a letter to Ashcroft and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld demanding safe transport to Afghanistan to meet with his client and instructing them to cease all interrogations of his client.

“For the first time in my legal career, no one even bothered to respond to me,” he says.

Meanwhile, news broke that Brosnahan was representing Lindh. Death threats poured in via telephone calls, e-mails and letters. He was forced to hire security guards at home, at the office, and for traveling to and from court. A lawyer from Ohio told Brosnahan that he planned to bring legal action against him for simply representing Lindh. The National Review called Brosnahan the “American Tali-Lawyer.”

Brosnahan wasn’t allowed to meet with his client for 54 days.

“John was horribly mistreated,” Brosnahan says.

“He was kept naked in a metal can—one of those containers used for shipping cargo. It had one hole in it for air. I don’t think it was legally torture, but it was horrible mistreatment.”

Lindh was no terrorist, according to Brosnahan. Instead, he was a teenager who went to study in Yemen and then agreed to join Afghan forces fighting against the Northern Alliance in that country’s civil war.

Brosnahan hired one of the nation’s leading terrorism experts, who had worked many times for the federal government, to spend time with and evaluate Lindh. The expert concluded that Lindh was no terrorist.

To prepare for possible trial, Brosnahan conducted a poll in northern Virginia, where the case was set to be tried, to gauge public attitudes.“It wasn’t good,” he says. “Thirty percent of the people wanted to give John the death penalty, and the government wasn’t even seeking death. But remember, this is just three months after the Sept. 11 attacks, so people were still very edgy.”

In the end, Brosnahan says, he had a very strong fact-based defense for Lindh. Because this was the first terrorism prosecution post-9/11, the government didn’t want to take any chances with a loss.

Brosnahan entered into plea negotiations with Michael Chertoff, who was at the time the chief of the criminal division at the U.S. Department of Justice.

“After we would talk, Chertoff would rush off to the White House or to see Rumsfeld to obtain approval for the deal,” Brosnahan says.

“I told him from the start that John would not plead to any of the terrorism counts because he had never fought against American forces and he had never intended to.”

The final deal provided for Lindh to plead guilty to lesser counts of supplying services to the Taliban, and carrying a rifle and two grenades. Lindh received a 20-year prison sentence. “I still remember the first words John ever spoke to me: ‘Boy, am I glad to see you.’ ”

Says Brosnahan: “That’s why I became a trial lawyer.”

JAMES J. BROSNAHAN

Born 1934 in Boston.

Firm Senior partner at Morrison & Foerster in San Francisco.

Law school Harvard.

Significant cases

1992—Prosecuted former Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger for his role in the Iran-Contra cover-up.

2002—Defended John Walker Lindh, aka the American Taliban, on charges he took up arms against the United States in Afghanistan. In a plea agreement, those allegations were dropped in favor of less serious charges that he supplied services to the Taliban.

2003—Defended the city of Oakland and Alameda County in an $836 million lawsuit brought by the Oakland Raiders for breach of promise. Jury awarded $34 million.

2007—Represented former Hewlett-Packard chair Patricia Dunn for her role in HP’s illegal obtaining of private phone records of journalists and HP board members. The charges were dismissed.

Other career highlights—Winner of the 2007 American Inns of Court Lewis F. Powell Jr. Award for Professionalism and Ethics.

Read about the other “Lions”:

Bernie Nussbaum: From Watergate to the World Trade Center

Joe Jamail: Keeping it simple

James Neal: Hating losing more than loving winning

Fred Bartlit: John Wayne in a pinstripe suit

Bobby Lee Cook: Kickin’ asses that needed kickin’

Richard “Racehorse” Haynes: The man they call when they’re in Texas-size trouble

Sidebar

Photo courtesy of James Brosnahan

Case U.S. v. Lindh.

Date July 2002.

Location U.S. courthouse in Alexandria, Va.

Who James Brosnahan (center) with Morrison & Foerster colleagues George Harris, Raj Chatterjee and Tony West.

What John Walker Lindh, a U.S. citizen captured on the battlefield in Afghanistan, is charged with taking up arms against American soldiers. Lindh’s legal team, led by Brosnahan, is heading toward a bank of reporters and photographers to field questions about Lindh’s decision to accept a plea bargain.

Note Lindh, who remains a devout Muslim, received a 20-year sentence.

Mark Curriden, an occasional contributor to the ABA Journal, is a freelance writer based in Dallas.