Insult to Injury: Texas Workers' Comp System Denies, Delays Medical Help

Photo of Ed Martin by Pam Francis

As Deputy Sheriff Ed Martin sat by his squad car in a fast-growing pool of his own blood, he called his wife and woke her at 3:30 a.m. He knew he might die from the point-blank shotgun blast that greeted him moments earlier when he knocked on a door for a 911 call in a tiny east Texas town called China.

“It’s pretty bad and I don’t know how it’s gonna turn out,” Martin told his wife as he awaited a helicopter medical evacuation. “Get the kids and meet me at the hospital.”

When they arrived, Martin was on a gurney and covered with a white sheet splotched red. His wife clutched their sleepy 2-year-old daughter to her chest as their sons, 6 and 10, stood at her side.

“I know it was tough for them,” Martin says, retelling the story of that night in June 2006 in the flat monotone of cop-speak. “But I wasn’t sure if I’d make it through surgery and I wanted to at least tell them ‘Hello’ and ‘I love you.’ ”

Doctors say Martin’s life was saved by his ballistic vest and the swift trip to the hospital in Beaumont, near the Gulf Coast and the Louisiana border. But the blast vaporized the skin of his inner arm down to bare muscle and tendons, and tore out the main artery.

A couple of weeks later, Martin got a phone call from an insurance adjuster handling his workers’ compensation claim. He was told the $7,300 helicopter ride was “not medically necessary” and likely would not be covered.

“Not medically necessary,” Martin says, repeating the phrase twice in succession five years after the shooting. “That was my first introduction to those words. And I’ve heard them a lot since then.”

While cops can’t be sure what lurks behind a door on an emergency call, they know the hazards. But Martin could not have foreseen the traps and trauma in store for him as he entered a state workers’ compensation system that was radically overhauled 20 years ago expressly to drive out lawyers representing injured workers, and that has grown ever friendlier to the insurance industry.

Martin, 45, has undergone 11 surgeries to repair his various injuries. He was away from work for two years. Such treatment is built in progressive stages, many of which—like his helicopter evacuation—were initially denied by the insurer and only later approved.

The chain of repeated denials of treatment not only kept him from recovering sooner but also left him with deep, nerve-enveloping scars that today cause sharp tingles he says feel like ants constantly biting his hand.

As a law enforcement officer, Martin knows it’s best to have backup. But he never had a lawyer to help him through the adversarial, multilevel administrative maze that is the Texas Department of Insurance’s Division of Workers’ Compensation. He never had an administrative hearing. His case played out in an endless stream of letters and phone calls between his doctor, an insurance adjuster and various division officials.

Martin was, however, assigned a case-manager nurse, who was at his side on most of his doctor visits and who helped him with paperwork. He later learned that she worked for the claims management company that was denying his medical treatment, and impeding his recovery and rehabilitation.

“I thought she was with the workers’ comp system,” Martin says. “She seemed outraged sometimes at what was happening to me.”

The Tristar Risk Management claims examiner who handled the case from the company’s Irving, Texas, regional office declined to discuss Martin’s complaints. “I can’t talk to you about this and I don’t think Tristar wants to talk to you about it,” says Nakilah Miller. “I’ll pass this request along to the lawyers.”

That was unavailing.

Martin says he missed his job as a detective in the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department, which has 60 deputies in law enforcement and another 200 on the corrections side. He returned in the summer of 2008, but it was far sooner than he and his doctor believe he should have. He had not yet regained full use of his left hand and even today it has only half the strength of his right. But the only alternative was to go without a paycheck because of unyielding workers’ comp timelines.

Deputy Martin’s workers’ comp nightmare is the “vision of what you get if you allow strictly cost containment and insurers running the system with no offset or balance,” says Kim Ross, a former vice president and chief lobbyist for the Texas Medical Association, and now a public affairs consultant and political strategist in Austin. “It’s not done from a practical standpoint of managing care properly, but simply by suppressing demand for medical services.”

While 22 other states have considered changes tightening their workers’ compensation programs in recent legislative sessions, it would be hard to find one that keeps legal fees as low, denials as high, and efforts of doctors and others to scam the system as plentiful as in Texas.

Even had Martin had a lawyer, it may not have made much difference in a claims system that critics charge is now wholly captive to the insurance companies that support it. It’s the result of a 20-year evolution larded with anti-tort politics. It wasn’t always so.

Once a stand-alone agency, the Division of Workers’ Compensation was run by a three-member board appointed by the governor: one from labor, one employer and a lawyer as chairman. Later it was recast with six part-time commissioners with a similar labor/employee split and a full-time executive director, to whom more of the power gravitated.

But in 2005 workers’ comp was brought into the Texas Department of Insurance—a regulatory agency long considered by critics as being too cozy with the insurance industry—where it is run by a single commissioner appointed by the governor.

But several decades of tweaking—through legislation, policy and business practices mostly meant to target scams by physicians and medical services providers—have gone beyond simple reform. Critics of the system say it has become so hostile, so skewed toward delay and denial that lawyers, physicians and even legitimate claimants have been driven away.

In the 1980s, Texas legislators decided that too many lawyers were involved in workers’ comp claims, and that something had to be done to stop skyrocketing costs for businesses and insurers. They enacted a severely restricted fee structure that made it nearly impossible for claimants-side lawyers to make a living wage. And it worked. Where previously hundreds of Texas lawyers had significant workers’ comp practices, there now are about 30.

“The goal was to get lawyers out of the system and leave more money for helping injured workers, and they got it half right,” says Rick Levy, a name partner in Austin’s Deats Durst Owen & Levy and a legal director for the Texas AFL-CIO. “So for a long time it’s been insurance companies and their lawyers going up against injured workers usually without lawyers. The unfairness of that is not difficult to discern.”

ONE OF THE FEW

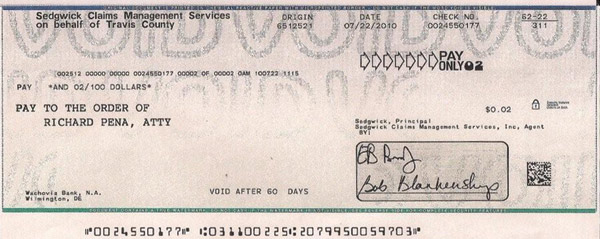

Legitimate claimants “often just become a statistic in society,” says Richard Pena, an Austin lawyer who has represented injured workers since the early 1980s—a rarity considering the state’s anti-lawyer campaign.

Pena is one lawyer who refused to walk away after the overhaul went into effect in 1991. He continued taking workers’ comp cases out of stubbornness and for moral reasons, though now he relies on personal-injury matters for most of his income. Handling benefits claims for injured workers brings in some of that.

Photo courtesy of Richard Pena

Pena keeps a copy of a check for 2 cents he received two summers ago in a workers’ comp case. Though admittedly the final payment on a somewhat larger amount, it is shockingly symbolic to any who see it.

Most would expect Pena to be a high roller. He is a former president of the State Bar of Texas and the Travis County (Austin) Bar Association, a former member of the ABA Board of Governors and former president of the American Bar Foundation. But Pena gets paid in only about one-third of the workers’ comp cases he takes, and typically receives about $70 a week for nine weeks—$630 per case. That entails workup, document gathering and administrative hearings, including battles against denials of medical necessity.

Lump-sum settlements were outlawed by the 1991 changes. If an insurer balks on a claim, everything must be hashed out in administrative proceedings. Medical and compensatory claims are bifurcated: Whether or not the worker was actually injured on the job must be fought out, determining if the claimant will get 70 percent of his salary while recuperating; also the necessity of medical treatment, as well as the extent to which any pre-existing conditions might partially offset covered treatments.

“Look, the real problem here is that insurance companies deny claims and medical treatment over and over, disputing claims carte blanche,” Pena says. “If the treatment request from a doctor is denied, it usually ends there.”

While Pena and a few others stayed on, a new breed of workers’ comp lawyer came in and has found a way to make a living. By digitalizing the process, many could make money through volume.

But unlike Pena, they turn away a lot more cases than they take. Lubbock lawyer John Gibson, for example, started handling claims for injured workers in 1997. He takes only cases in which he can expect to make a living: high-wage earners (no chain-store greeters, as much as he would like to); serious injuries (removal of disks from the spine don’t make his cut because those patients return to work quickly); and, emphasizing the last detail, only those who have been out of work for a significant period of time.

Gibson says things have worsened for injured workers in recent years, mostly through medical denials and delays. He laughs when asked to do what few risk-averse lawyers would—go on the record criticizing the powerful Texas Department of Insurance’s Division of Workers’ Compensation.

“I’m already suing them,” he says, “and I suppose you can’t be more critical than that.”

Gibson took the department to federal court in Lubbock after the agency’s perplexing demand last winter that his blog be removed from the Internet. For several years his workers’ comp website highlighted cases and concerns about the division and insurance carriers, heavy on facts and analysis with a strong point of view. A January post, for example, probed law and policy issues in his November jury win over Texas Mutual Insurance, which has the biggest slice of the state’s workers’ comp pie.

In February the department sent Gibson a cease-and-desist letter and threatened to sanction him up to $25,000 a day if the offending website remained up. The site allegedly broke the law by using the terms Texas, workers’ compensation and workers’ comp.

A 2005 state statute cracked down on unscrupulous entrepreneurs who might draw on those words to imply they are officially part of the Division of Workers’ Compensation. It is now illegal to use the terms in connection with “any impersonation, advertisement, solicitation, business name, business activity, document, product or service.”

The department investigates violators of the gapingly broad statute only after receiving a complaint. So someone had dropped a dime on Gibson. On sketchy information, he believes the agency has gone after just one physician and two lawyers, both claimants’ side. The TDI-DWC won’t reveal enforcement details.

A whole lot of others probably have run afoul of the statute. Indeed, annually for the past 42 years, a prominent defense-side firm in Austin has published the authoritative Texas Workers’ Compensation Manual, the cover of which apparently uses the words illegally while it is prominently displayed on the firm’s website.

Gibson, Pena and others on the claimants’ side believe both the statute and its selective enforcement add yet more evidence that the workers’ comp system in Texas has become captive to the insurance industry.

Questions about enforcement of the statute and other matters were posed to TDI-DWC spokesman John Greeley, who asked for them to be put in writing. After receiving them, he didn’t respond. An open records request to the TDI-DWC asked two questions: What was the date of the complaint it received concerning Gibson’s blog, and how many similar cease-and-desist letters has it sent out? The TDI’s legal office declined to provide the information under public disclosure laws, citing an exemption for pending litigation. It asked the state attorney general’s office to rule on its decision and the AG agreed.

Greeley did not return a phone call seeking a subsequent interview with division officials on various matters, and a request to TDI-DWC Commissioner Rod Bordelon’s office for an interview went unanswered.

Texas is the only state where participation in a workers’ comp system is not mandatory for employers above a certain size. (New Jersey technically has the option, but it is so strict as to be preclusive.) Most Texas employers carry workers’ comp insurance, but 32 percent of them are so-called nonsubscribers and employ an estimated 17 percent of the workforce—1.7 million people. Many of those have private plans, but some go completely bare.

Thus Texas Mutual has good reason to limit payouts as much as it can. Competition from private plans combined with a cyclically soft market have driven down the average workers’ comp premium for each $100 of payroll by about half since the early 2000s, now at $1.47. To keep from losing business, Texas Mutual, chartered by the state in 1991, has paid out $1 billion in policyholder dividends since 1998, most of it in the past four years. (In its 2010 annual report posted online, Tex as Mutual reports “claim benefits paid and incurred” as $381 million and the dividend payout for that year as $116 million.)

That’s at a time when the customer base was not growing and income from premiums headed down. One indication of how Texas Mutual still managed to prosper is buried in dry, bureaucratic reporting by the state insurance department.

In its 2006 biennial report to the legislature, the insurance department noted that since 2001 the majority of denied claims were deemed “not medically necessary” (before that, the problem had more often been improper paperwork), and that “an increasing percentage of these denials” stemmed from second opinions by peer-review doctors hired by the carriers.

A similar 2008 report added that a possible explanation for stabilization of medical costs might be “denials of both workers’ compensation claims and medical services over time.” Medical costs were finally being held in check, in part at the expense of injured workers.

ON THE RECORD

Fed up with denials of medical procedures for their workers’ comp patients, a San Antonio medical group with nine neurosurgeons and an orthopedic surgeon installed a recording device on an office telephone in 2005 for dealing with denials.

They did so, one of the neurosurgeons said in a deposition in a bad-faith insurance case now at the Texas Supreme Court, because “there were some occasions that were so egregious that nobody would believe it if we said it, and so we decided to document it.”

The device was first used on a call from Texas Mutual’s medical director, Dr. Nicholas Tsourmas, known among claimants’ lawyers as “Dr. No.” Tsourmas also has a medical practice and does similar case review work for other insurers. He did not respond to an interview request.

Last year the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at New Orleans harshly condemned Tsourmas for recrafting an opinion at the request of an insurer. Initially, the doctor had determined there was not enough evidence to conclude that an injured worker was capable of resuming work. He asked to see MRIs (which the carrier had) and for additional X-rays. Instead, he was told the records were not available and was urged to make a finding on the worker’s functionality. Tsourmas then said the man could work.

The 5th Circuit said in Scheuermann v. Unum Life Insurance Co. that Tsourmas’ addendum was based on no further medical evidence and was “in plain conflict with the medical records.”

Nevertheless, Tsourmas receives the highest compliment from Mary Barrow Nichols, Texas Mutual’s senior vice president and general counsel. “I’d trust my family to him,” Nichols says, when told of these complaints.

TMI staff attorney Shannon Pounds adds that on many occasions Tsourmas has disagreed with the carrier and said a particular worker needs surgery, “and we do it.” And Richardson, Texas, claimants’ lawyer Matthew Lewis says, “To be fair to all these doctors, the only time we really see their names is when they deny something. Only the disapproved cases are news to us.”

More than plenty are indeed worthy of denials. Overtreatment and overutilization of medical services is almost a constant problem in Texas. In 2003, the legislature imposed Medicare fee schedules on workers’ comp to control costs. But that drove out a lot of the best doctors, and many of them were replaced by others who knew how to play the new system.

“A lot of them stopped taking workers’ comp patients,” says Ross, the former Texas Medical Association lobbyist. “So a second tier and tertiary tier of physicians stepped up, and you got the excessive, repeated, unnecessary spine surgeries and the ‘pop-up’ pain clinics handing out pills.

“We predicted it. I warned against an across-the-board approach. You end up with patient-milling,” he says. “But the carriers, the state and the business interests wanted budget certainty. And they never fixed the underlying plumbing.”

Thus, says Robert Briscoe, principal and senior consultant with the nationwide independent actuarial and consulting firm Milliman Inc., “Texas is worse than other states. Those of us who do comp marvel at how south Texas doctors are doing multiple back surgeries—two, four or five—on one person. That the doctors talk them into it blows your mind. And the natural reaction of claims handlers is to fight battles and deny.” Which leads to some legitimate claims being denied, often for alleged pre-existing conditions dubbed “ordinary diseases of life.”

“I’d get so tired of picking up a file and seeing those same words, ‘ordinary disease of life,’ ” says John Cain, who retired in February as the associate director of an ombudsman program that uses nonlawyers to assist injured workers in their battles with insurance carriers.

The ombudsman system, part of the 1991 change, has morphed from handing out basic information to accompanying claimants in administrative hearings, if requested by injured workers. Because of complaints about ombudsman ineffectiveness, the legislature in 2005 created the Office of Injured Employee Counsel within the Texas Department of Insurance and put them there.

Cain began his career in the state workers’ comp system in 1969 and spent 30 years there, interrupted by two stints totaling 12 years doing similar work in the private sector.

“Sometimes they just create a controversy as to whether they owe on a claim,” Cain says of the carriers. “They’ll get a peer-review report and use it as justification to suspend medical benefits or require an exam by a doctor of their choice, who will say there was a pre-existing injury. And adjusters sometimes take a hard line even when you can tell their heart’s not in it. Some others seem to enjoy it.”

The climb through the system can be steep. Even if an injured worker overcomes denials through three administrative levels within the division, the insurance carrier can appeal for judicial review in state court. If the claimant wins there, for the first time in the process the carriers must pay any lawyer’s fees and costs. Up to this point, a lawyer would have been paid only 25 percent taken from the claimant’s income benefits, with even that severely capped.

Still, an injured worker’s chance of getting a lawyer for state court is so slight, the OIEC has asked the legislature in its past three sessions to fund appointed lawyers. The claimants can win every issue in the workers’ comp process “only to lose on a default judgment in district court solely due to a lack of representation,” according to the request last fall.

Those who manage to get lawyers usually win, says Gibson, who previously blogged about such matters.

“Once juries hear the facts,” he says, “it can be like shooting fish in a barrel. They hate the insurance companies.”

Texas Mutual is known for more readily taking cases to judicial review than other carriers. Unlike many of its competitors, it offers only workers’ comp insurance and only in one state.

“I think that [assessment is] fair; we don’t always agree with how the agency applies law,” says Nichols, adding that “we have the biggest market share so we have to care more than anybody else. Those decisions affect us more than they do the multistate carriers.”

There is another wrinkle in the system that gives incentive for insurance carriers to battle medical claims all the way through judicial review: If the carrier wins, it can recover every dime spent on the claim from something called the Subsequent Injury Fund. Carriers sometimes receive payments in the hundreds of thousands of dollars from the fund on single cases, even for lost wages claims. Those payouts totaled about $5 million in 2010, nearly doubling since 2007.

The special fund was created to make injured workers more employable by taking prospective employers off the hook should the worker be injured again and qualify for lifetime benefits. But such instances are rare. Most of the money stays in the fund and goes back to insurance carriers after they prevail in disputed claims, typically against lawyerless claimants.

The failed legislative proposals for appointed counsel suggested paying for legal representation out of the Subsequent Injury Fund.

Texas is the only state to supply such a fund strictly with unpaid benefits. Beneficiaries of workers killed on the job get an amount equal to seven years of the worker’s pay from workers’ comp insurance. If there are no beneficiaries, the money goes into the fund.

And the fund remains flush. Texas led the nation with 480 fatal occupational injuries in 2009, according to the most recent report by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Claimants’ lawyers complain that carriers can game the fund in both directions, not only receiving money from it when they shouldn’t, but also not paying into it when they should. They can deny a death was work-related; and if no survivors challenge it, the carriers often don’t have to pay into the fund.

The Texas State Supreme Court.

PUSHBACK

While carriers have incentives to take cases to judicial review, lawyers pushed back in recent years with increasing numbers of high-dollar victories in bad-faith claims. Some insurers were easing off in DWC proceedings because of that threat, says Austin lawyer Joe Longley, who drafted many of the consumer protection provisions in the insurance code as chief of the antitrust and consumer protection division of the Texas attorney general’s office in the early 1970s.

But in August the Texas Supreme Court struck that remedy a potentially devastating blow in Texas Mutual Insurance Co. v. Ruttiger. The court ruled that bad-faith claims are not permitted under the insurance code because it does not enumerate them.

Two dissenting justices said the court was overturning its own precedent and, in effect, rewriting a statute. The labor code made specific exception for actions by insurance carriers that were following orders from the TDI-DWC; and, the dissenters argue, that implies the legislature did not intend to eliminate other bad-faith claims.

“These cases had become the only check and balance injured workers had against the carriers because they could cost so much more money than the injury claims themselves, plus attorney fees,” Longley says.

And lawyers likely will move away from helping injured workers in bad-faith matters because, as the legislature set out to do in the workers’ comp overhaul, Ruttiger removes a big incentive: Cases brought under the insurance code would allow for attorney fees and costs. The court did say that some common-law claims might still be brought, for which attorney fees can be recovered.

“That’s really big because it costs a lot to do a case,” says Michael Doyle of Houston’s Doyle Raizner law firm, who handled Ruttiger and has three other bad-faith claims in a logjam at the state supreme court. Those others might be whittled or scuttled with per curiam decisions after Ruttiger.

Doyle primarily does maritime work, but 10-plus years ago he began developing a side niche in bad-faith workers’ comp cases.

Doyle asked for a rehearing, and he says Ruttiger will prove yet another major disincentive for lawyers who might otherwise help injured workers needing representation in court.

Deputy Martin never received any kind of adjudication, having unwittingly put himself at the mercy of the workers’ comp system with no lawyer or ombudsman. That gave insurance adjusters even easier bites at the apple, stretching out his treatment and cutting short his benefits.

The final straw came when the division brought in a “designated doctor,” at the insurer’s request, to review Martin’s doctor’s findings.

The reviewing doctor determined that, although Martin had reached what is called maximum medical improvement, he was still significantly disabled. That second opinion included an impairment rating of 26 percent, well above the 15 percent cutoff that marks the difference in receiving income benefits for just two years or for as long as eight.

But then Tristar, the third-party administrator handling workers’ comp claims for Martin’s employer, Jefferson County, picked yet another physician to review the second opinion without personally examining the deputy. It led to a rating of just 11 percent.

“So I went back to work,” says Martin, who very much intended to do so when able, but who felt this was yet another in a series of bum’s rushes.

In April 2010, Martin told a brief version of his story to the Texas House Committee on State Affairs as it considered a bill to ensure that first responders get expedited consideration in the workers’ comp system. The proposal failed., but the language was tucked into later legislation that passed.

Other states wrestle with some of the same issues, but Texas is different because the lawyers are so marginalized and the state’s unique option for private workers’ comp plans makes the insurance industry even more competitive. Quietly, some carrier-side lobbyists have cautioned that if the playing field appears tilted too much their way, it could result in a backlash, though the Texas legislature is decidedly conservative and pro-business.

In the background, the prospect of nationwide health care reform carries with it the possibility of making medical costs, the most expensive aspect of workers’ compensation, moot.

But for now, a lot of earnest lawyers are saying that a lot of genuinely injured workers are being denied their due—often to a terrible end.

In the summer of 2010, a Fort Worth orthopedic surgeon asked the Texas legislature to require that a final decision on workers’ comp coverage for medical care be made within 10 to 14 days, or three weeks at most.

Dr. Stephen Wilson testified that he and other physicians believe prolonged battles over medical denials have led to suicides in recent years.

“The incidence of those reports has been astonishingly high compared to five years ago,” he told the legislators, “when they were, to my knowledge, nonexistent.”

Clarification

The print and initial Web versions of “Insult to Injury,” September, should have noted that the legislation to ensure first responders get expedited consideration in the workers’ compensation system was defeated in committee, but the key elements of it were later passed after being tacked on to other legislation.