Increased enforcement of immigration laws has raised the risk of scams

Shutterstock

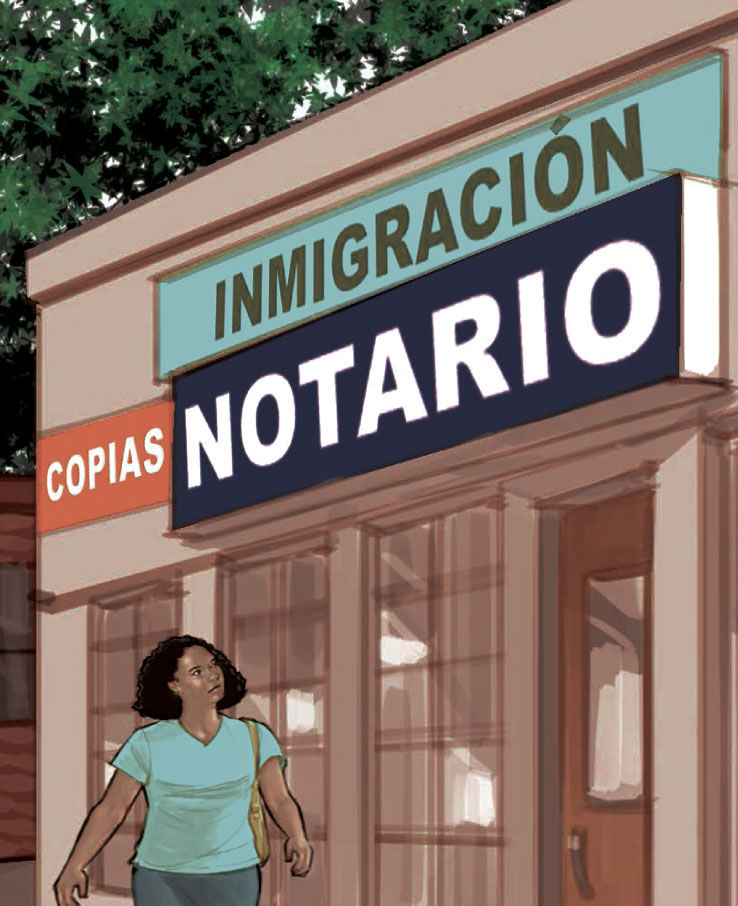

Alicia, an immigrant from El Salvador, had plenty of time to renew her work permit under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. Unfortunately, she went to a “notario” for help.

Alicia, who is using a pseudonym because of the uncertainty of her immigration status, was brought to the United States at age 11 and lives in Maryland. That made her eligible for the Obama administration’s DACA program, which grants two-year work permits to young people who came to the United States illegally as minors, deferring any deportations during that time.

She started the DACA renewal process in late August and then left for Texas, where she had a job helping with restoration and cleaning after Hurricane Harvey. Not long afterward, Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the government was canceling DACA, creating a hard Oct. 5 deadline for renewal applications. Feeling nervous, she called the person she’d hired to make sure the application had been sent in. He assured her it was.

Art courtesy of the Federal Trade Commission

It wasn’t. Alicia had gone to a notario, a kind of nonlawyer who exploits a mistranslation of “notary public” to convince Spanish speakers he’s licensed to practice law. The notario stopped answering Alicia’s calls—and when she contacted the federal government directly, she discovered that her application had never been received. That means her work permit was set to expire early this year—and with it her chance to get better jobs. However, thanks to court rulings, she’s been able to renew it and is able to work in the U.S. until early 2020.

“I believed … he was going to send it because he’d never let me down,” says Alicia, who had used the same notario for prior DACA applications. “He told me that there were a lot of other kids, students, who’d called for the same reason, and he was going to look into it and see what was going on. And that he was going to call me back, but he never called me back.”

Anne Schaufele of the Washington, D.C., immigration public-interest firm Ayuda, is now representing Alicia. She says there’s very little chance the federal government will bend deadlines in recognition of fraud. And Schaufele suspects there are lots more Alicias.

“What we see from our receptionist, who answers calls all day long, is that whenever there’s a change [in the law], she gets a flood of additional calls,” says Schaufele, who runs Ayuda’s Project END (Ending Notario Deceit). “In the absence of licensed practitioners, … folks are going to nonattorneys that are capitalizing on this [increased] interest.”

In fact, advocates say immigration legal-services fraud jumps every time there’s a change in the law. In the first year under President Donald Trump, immigration law saw multiple high-profile changes. That included a 42 percent increase in arrests by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, according to a report from the agency; the cancellation of DACA and temporary protected status; and the end of broad prosecutorial discretion in immigration court. The Trump administration is not itself responsible for any fraud that results. Still, advocates say changes could frighten immigrants into the arms of cut-rate fake attorneys.

Christy Williams: “We’re looking at thousands of people who may not have [legal immigration] status, and that’s in addition to thousands and thousands of people who are already undocumented.” Photograph courtesy of Catholic Legal Immigration Network Inc.

“With the recent announcement on DACA, we’re looking at thousands of people who may not have [legal immigration] status, and that’s in addition to thousands and thousands of people who are already undocumented,” says Christy Williams, who leads the project on unauthorized practice of immigration law at the Catholic Legal Immigration Network Inc. in Washington, D.C. “I suspect that bad actors will see this as an opportunity to prey on people who are in desperate circumstances right now.”

EXPLOITING ANXIETY

Fraud targeting immigrants did not begin with the Trump administration; advocates say it’s constant and pervasive. But the administration’s aggressive approach to immigration law enforcement is driving up interest in legal services, they say. And some subset of those immigrants looking for help will end up trusting the wrong people.

“I think always when people are afraid, they may go out looking to see if there’s anything they can do about their case,” says Camille Mackler, director of immigration legal policy for the New York Immigration Coalition. “There are more people who are going to try to prey on that.”

Scams vary, but fraudulent nonlawyers typically take the client’s money, then do either incompetent work or no work at all. Some may truly mean to help, but others draw their clients in with outright lies, citing “new laws” or a friend in the federal government who can be bribed. When the clients wise up and ask for their money and documents back, the scammer may ignore them, withhold documents or even threaten to turn them in to immigration authorities.

Correction

Print and initial online versions of "Legal Prey," May, should have identified Vanessa Stine as a staff attorney at Friends of Farmworkers. Her Equal Justice Works fellowship ran from 2014 to 2016.The Journal regrets the error.

This article was published in the May 2018 issue of the ABA Journal with the title "Legal Prey: Increased enforcement of immigration laws has raised the risk of scams."

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.