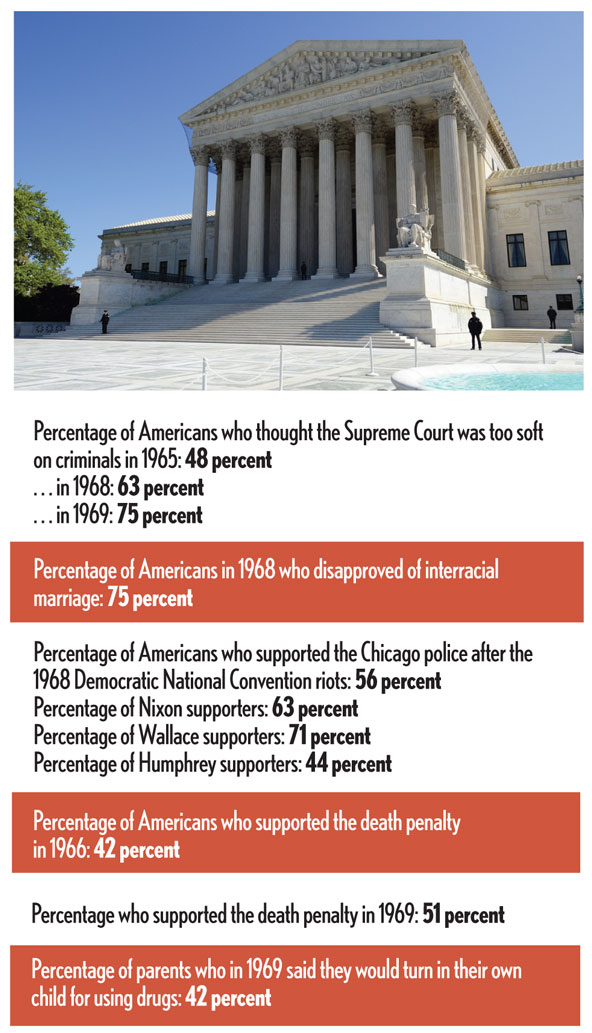

How did America's police become a military force on the streets?

Editor’s Note: In a remarkable speech at the National Defense University in May, President Barack Obama signaled an end to the war on terrorism; maybe not an end, it turns out, but a winding down of the costly deployments, the wholesale use of drone warfare, and even the very rhetoric of war. Click here to read the full editor’s note.

Are cops constitutional?

In a 2001 article for the Seton Hall Constitutional Law Journal, the legal scholar and civil liberties activist Roger Roots posed just that question. Roots, a fairly radical libertarian, believes that the U.S. Constitution doesn’t allow for police as they exist today. At the very least, he argues, police departments, powers and practices today violate the document’s spirit and intent. “Under the criminal justice model known to the framers, professional police officers were unknown,” Roots writes.

Civil liberties activists say our nation’s police forces have become too militaristic—like this SWAT team participating in a drill in October–and are deployed even in nonviolent situations. Photo by AP/Elaine Thompson.

The founders and their contemporaries would probably have seen even the early-19th-century police forces as a standing army, and a particularly odious one at that. Just before the American Revolution, it wasn’t the stationing of British troops in the colonies that irked patriots in Boston and Virginia; it was England’s decision to use the troops for everyday law enforcement. This wariness of standing armies was born of experience and a study of history—early American statesmen like Madison, Washington and Adams were well-versed in the history of such armies in Europe, especially in ancient Rome.

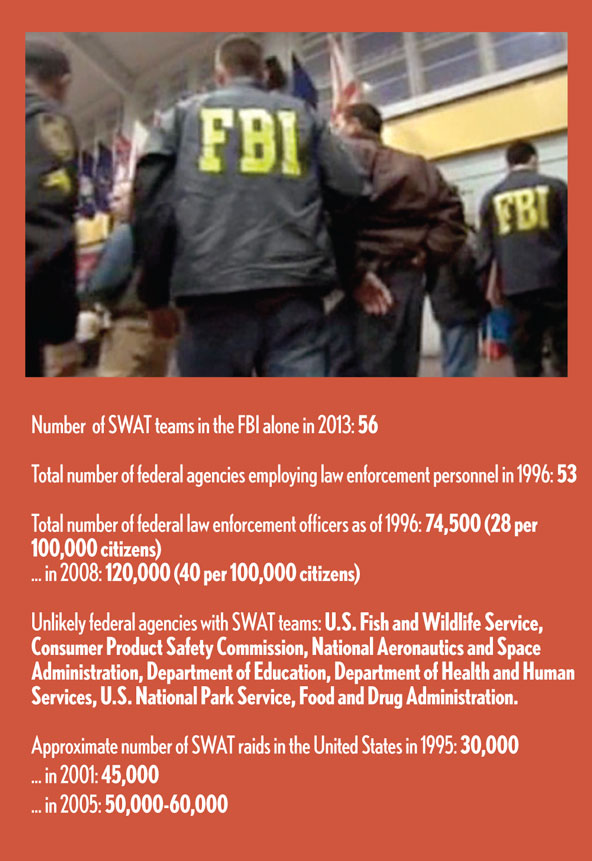

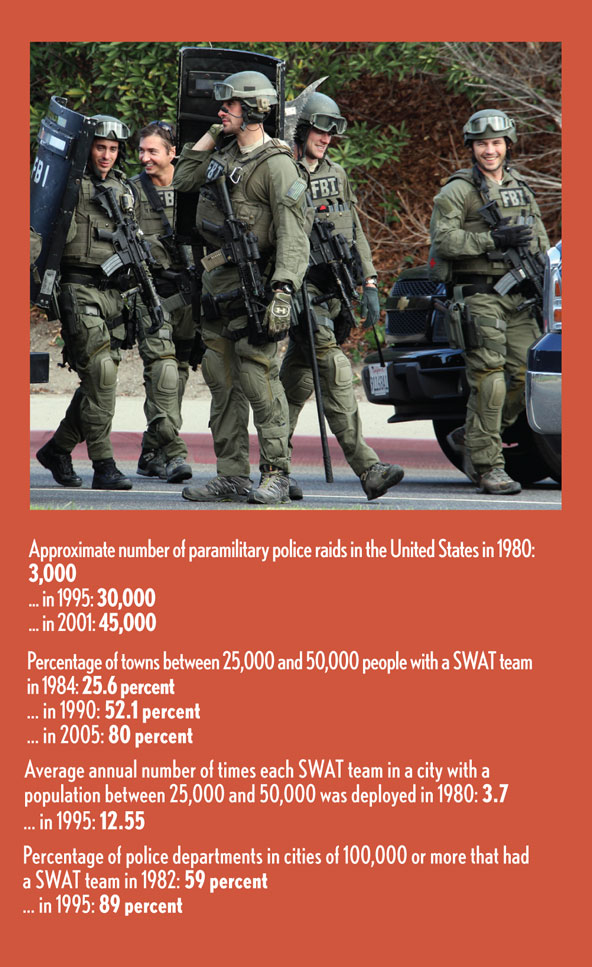

If even the earliest attempts at centralized police forces would have alarmed the founders, today’s policing would have terrified them. Today in America SWAT teams violently smash into private homes more than 100 times per day. The vast majority of these raids are to enforce laws against consensual crimes. In many cities, police departments have given up the traditional blue uniforms for “battle dress uniforms” modeled after soldier attire.

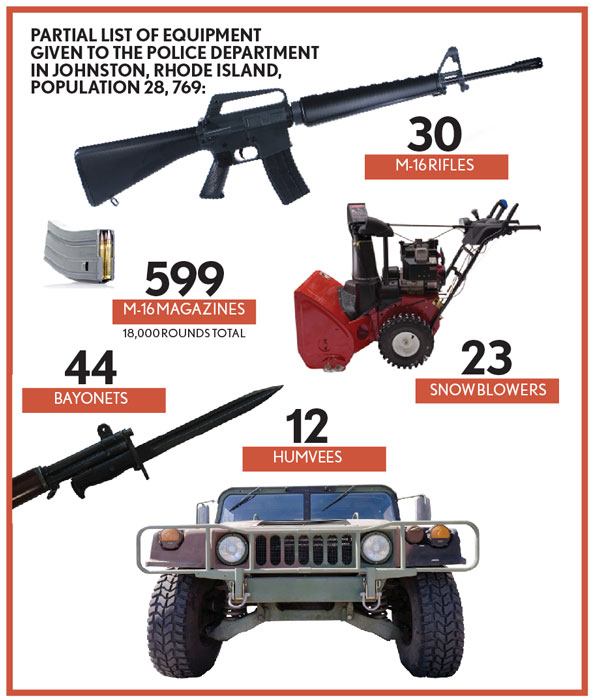

Police departments across the country now sport armored personnel carriers designed for use on a battlefield. Some have helicopters, tanks and Humvees. They carry military-grade weapons. Most of this equipment comes from the military itself. Many SWAT teams today are trained by current and former personnel from special forces units like the Navy SEALs or Army Rangers. National Guard helicopters now routinely swoop through rural areas in search of pot plants and, when they find something, send gun-toting troops dressed for battle rappelling down to chop and confiscate the contraband. But it isn’t just drugs. Aggressive, SWAT-style tactics are now used to raid neighborhood poker games, doctors’ offices, bars and restaurants, and head shops—despite the fact that the targets of these raids pose little threat to anyone. This sort of force was once reserved as the last option to defuse a dangerous situation. It’s increasingly used as the first option to apprehend people who aren’t dangerous at all.

OUR ‘RUNT PIGLET’ AMENDMENT

Ron Sachs/CNP—© Ron Sachs/CNP/Corbis/AP Images

The Third Amendment reads, in full: “No soldier shall, in time of peace, be quartered in any house without the consent of the owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.”

You might call it the runt piglet of the Bill of Rights amendments—short, overlooked, sometimes the butt of jokes. The Supreme Court has yet to hear a case that turns on the Third Amendment, and only one such case has reached a federal appeals court. There have been a few periods in American history when the government probably violated the amendment [the War of 1812, the Civil War and on the Aleutian Islands during World War II], but those incursions into quartering didn’t produce any significant court challenges. Not surprisingly, then, Third Amendment scholarship is a thin field, comprising just a handful of law review articles, most of which either look at the amendment’s history or pontificate on its obsolescence.

Given the apparent irrelevance of the amendment today, we might ask why the framers found it so important in the first place. One answer [lies in] the “castle doctrine.” If you revere the principle that a man’s home is his castle, it hardly seems just to force him to share a portion of it with soldiers—particularly when the country isn’t even at war. But the historical context behind the Third Amendment shows that the framers were worried about something more profound than fat soldier hands stripping the country’s larders.

At the time the Third Amendment was ratified, the images and memories of British troops in Boston and other cities were still fresh, and the clashes with colonists that drew the country into war still evoked strong emotions. What we might call the “symbolic Third Amendment” wasn’t just a prohibition on peacetime quartering, but a more robust expression of the threat that standing armies pose to free societies. It represented a long-standing, deeply ingrained resistance to armies patrolling American streets and policing American communities.

And, in that sense, the spirit of the Third Amendment is anything but anachronistic.

As with the castle doctrine, colonial America inherited its aversion to quartering from England. And as with the castle doctrine, England wasn’t nearly as respectful of the principle in the colonies as it was at home. The first significant escalation of the issue came in the 1750s, when the British sent over thousands of troops to fight the Seven Years’ War (known in the United States as the French and Indian War). In the face of increasing complaints from the colonies about the soldiers stationed in their towns, Parliament responded with more provocation. The Quartering Act of 1765 required the colonists to house, feed and supply British soldiers (albeit in public facilities). Parliament also helpfully provided a funding mechanism with the hated Stamp Act.

Protests erupted throughout the colonies, [and] some spilled over into violence, most notably the Boston Massacre in 1770. England only further angered the colonists by responding with even more restrictions on trade and imports. Parliament then passed a second Quartering Act in 1774, this time specifically authorizing British generals to put soldiers in colonists’ homes. The law was aimed squarely at correcting the colonies’ insubordination. England then sent troops to emphasize the point.

Using general warrants, British soldiers were allowed to enter private homes, confiscate what they found, and often keep the bounty for themselves. The policy was reminiscent of today’s civil asset forfeiture laws, which allow police to seize and keep for their departments cash, cars, luxury goods and even homes, often under only the thinnest allegation of criminality.

AP Photo/Greg Gibson

A BATTLE OVER ARMIES

After the American Revolution, the leaders of the new American republic had some difficult decisions to make. They debated whether the abuses that British soldiers had visited upon colonial America were attributable to quartering alone or to the general aura of militarism that came with maintaining standing armies in peacetime—and whether restricting, prohibiting or providing checks on either practice would prevent the abuses they feared.

Antifederalists like George Mason, Patrick Henry, Sam Adams and Elbridge Gerry opposed any sort of national army. They believed that voluntary, civilian militias should handle issues of national security. To a degree, the federalists were sympathetic to this idea. John Adams, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison had all written on the threat to liberty posed by a permanent army. But the federalists still believed that the federal government needed the power to raise an army.

In the end, the federalists won the argument. There would be a standing army. But protection from its potential threats would come in an amendment contained in the Bill of Rights that created an individual right against quartering in peacetime. Even during wartime, quartering would need to be approved by the legislature, the branch more answerable to the people than the executive.

Taken together, the Second, Third and Tenth amendments indicate the founders’ desire for the power to enforce laws and maintain order to be primarily left with the states. As a whole, the Constitution embodies the rough consensus at the time that there would be occasions when federal force might be necessary to carry out federal law and dispel violence or disorder that threatened the stability of the republic, but that such endeavors were to be undertaken cautiously, and only as a last resort.

More important, the often volatile debate between the federalists and the antifederalists shows that the Third Amendment itself represented much more than the sum of its words. The amendment was in some ways a compromise, but it reflects the broader sentiment—shared by both sides—about militarism in a free society. Ultimately, the founders decided that a standing army was a necessary evil, but that the role of soldiers would be only to dispel foreign threats, not to enforce laws against American citizens.

FEDERAL FORCE ARISES

Before the Bill of Rights could even be ratified, however, a rebellion led by a bitter veteran tested those principles. Daniel Shays was part of the Massachusetts militia during the Revolutionary War. He was wounded in action and received a decorative sword from the French general the Marquis de Lafayette in recognition of his service.

After the war ended, Shays returned to his farm in Massachusetts. It wasn’t long before he began receiving court summonses to account for the debts he had accumulated while he was off fighting the British. Shays went broke. He even sold the sword from Lafayette to help pay his debts. Other veterans were going through the same thing.

The debt collectors weren’t exactly villains either. Businesses too had taken on debt to support the war. They set about collecting those debts to avoid going under. Shays and other veterans attempted to get relief from the state legislature in the form of debtor protection laws or the printing of more money, but the legislature balked.

In the fall of 1786, Shays assembled a group of 800 veterans and supporters to march on Boston. The movement subsequently succeeded in shutting down some courtrooms, and some began to fear that it threatened to erupt into a full-scale rebellion.

In January 1787, Massachusetts Gov. James Bowdoin asked the Continental Congress to raise troops to help put down the rebels, but under the Articles of Confederation the federal government didn’t have the power. So Bowdoin instead assembled a small army of mercenaries paid for by the same creditors who were hounding men like Shays. After a series of skirmishes, the rebellion had been broken by the following summer.

Shays’ Rebellion was never a serious threat to overthrow the Massachusetts government—much less that of the United States—and it was put down relatively quickly, without the use of federal troops and with little loss of life beyond the rebels themselves. But its success in temporarily shutting down courthouses in Boston convinced many political leaders in early America that a stronger federal government was needed. Inadvertently, Shays spurred momentum for what became the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia.

The impact of Shays’ Rebellion didn’t end, however, at Philadelphia. Memories of the rebellion and fears that something like it could destabilize the new republic blunted memories of the abuses suffered at the hands of British troops and made many in the new government more comfortable with the use of federal force to put down domestic uprisings.

In 1792, just five years after the ratification of the Bill of Rights, Congress passed the Calling Forth Act. The new law gave the president the authority to unilaterally call up and command state militias to repel insurrections, fend off attacks from hostile American Indian tribes, and address other threats that presented themselves while Congress wasn’t in session. In addition to the concerns raised by Shays’ Rebellion, growing discontent over one of the country’s first federal taxes—a tax on whiskey—was also making the law’s supporters anxious. Two years later, in 1794, President George Washington used the act to call up a militia to put down the Whiskey Rebellion in western Pennsylvania.

So ideas about law and order were already evolving. The young republic had gone from a country of rebels lashing out at the British troops in their midst to a country with a government unafraid to use its troops to put down rebellions. But American presidents had still generally adhered to the symbolic Third Amendment. For the first 50 years or so after ratification of the Constitution, military troops were rarely, if ever, used for routine law enforcement. But, over time, that would change.

AP Photo/APTN, Pool

SLOW CHANGE

The Civil War and Reconstruction rekindled historic antipathy toward the use of military troops in the streets. And four major wars during the 20th century kept militarization in its intended context—protecting Americans by fighting overseas.

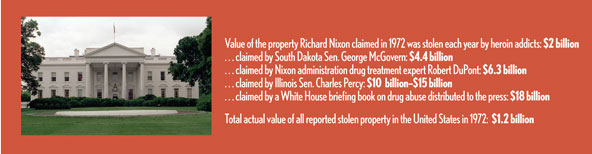

But as the Vietnam War abated, policymakers turned the war footing inward, transforming law enforcement against illegal drugs into a “war.” There was nothing secretive about this transformation. President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs” in June 1971. But as that war has unfolded over several decades, we seem not to have noticed its implications.

On Feb. 11, 2010, in Columbia, Mo., the police department’s SWAT team served a drug warrant at the home of Jonathan Whitworth, his wife and their 7-year-old son. Police claimed that eight days earlier they had received a tip from a confidential informant that Whitworth had a large supply of marijuana in his home. They then conducted a trash pull, which turned up marijuana “residue” in the family’s garbage. That was the basis for a violent, nighttime, forced-entry raid on the couple’s home. The cops stormed in screaming, swearing and firing their weapons; and within seconds of breaking down the door they intentionally shot and killed one of the family’s dogs, a pit bull. At least one bullet ricocheted and struck the family’s pet corgi. The wounded dogs whimpered in agony. Upon learning that the police had killed one of his pets, Whitworth burst into tears.

The Columbia Police Department SWAT team recorded many of its drug raids for training purposes, including this one. After battling with the police over its release, a local newspaper was finally able to get the video through state open records laws and posted it to the Internet. It quickly went viral, climbing to over 1 million YouTube views within a week. People were outraged.

The video also made national headlines. On Fox News, Bill O’Reilly discussed it with newspaper columnist and pundit Charles Krauthammer, who assured O’Reilly’s audience that botched raids like the one in the video were unusual; he warned viewers not to judge the war on drugs based on the images coming out of Columbia. Krauthammer was wrong. This was not a “botched” raid. In fact, the only thing unusual about the raid was that it was recorded. Everything else—from the relatively little evidence to the lack of a corroborating investigation, the killing of the dog, the fact that the raid was for nothing more than pot, the police misfiring and their unawareness that a child was in the home—was fairly standard. The police raided the house they intended to raid, and they even found some pot. The problem for them was that possession of small amounts of pot in Columbia had been decriminalized. They did charge Whitworth with possession of drug paraphernalia for the pipe they found near the marijuana—a $300 fine.

Most Americans still believe we live in a free society and revere its core values. These principles are pretty well-known: freedom of speech, religion and the press; the right to a fair trial; representative democracy; equality before the law; and so on. These aren’t principles we hold sacred because they’re enshrined in the Constitution, or because they were cherished by the founders. These principles were enshrined in the Constitution and cherished by the framers precisely because they’re indispensable to a free society. How did we get here? How did we evolve from a country whose founding statesmen were adamant about the dangers of armed, standing government forces—a country that enshrined the Fourth Amendment in the Bill of Rights and revered and protected the age-old notion that the home is a place of privacy and sanctuary—to a country where it has become acceptable for armed government agents dressed in battle garb to storm private homes in the middle of the night—not to apprehend violent fugitives or thwart terrorist attacks, but to enforce laws against nonviolent, consensual activities?

How did a country pushed into a revolution by protest and political speech become one where protests are met with flash grenades, pepper spray and platoons of riot teams dressed like RoboCops? How did we go from a system in which laws were enforced by the citizens—often with noncoercive methods—to one in which order is preserved by armed government agents too often conditioned to see streets and neighborhoods as battlefields and the citizens they serve as the enemy?

Although there are plenty of anecdotes about bad cops, there are plenty of good cops. The fact is that we need cops, and there are limited situations in which we need SWAT teams. If anything, bad cops are the product of bad policy. And policy is ultimately made by politicians. A bad system loaded with bad incentives will unfailingly produce bad cops. The good ones will never enter the field in the first place, or they will become frustrated and leave police work, or they’ll simply turn bad. At best, they’ll have unrewarding, unfulfilling jobs. There are consequences to having cops who are too angry and too eager to kick down doors, and who approach their jobs with entirely the wrong mindset. But we need to keep an eye toward identifying and changing the policies that allow such people to become cops in the first place—and that allow them to flourish in police work.

A COP REMEMBERS

Betty Taylor still remembers the night it all hit her.

As a child, Taylor had always been taught that police officers were the good guys. She learned to respect law enforcement, as she puts it, “all the time, all the way.” She went on to become a cop because she wanted to help people, and that’s what cops did. She wanted to fight sexual assault, particularly predators who take advantage of children. To go into law enforcement—to become one of the good guys—seemed like the best way to accomplish that. By the late 1990s, she’d risen to the rank of detective in the sheriff’s department of Lincoln County, Mo.,—a sparsely populated farming community about an hour northwest of St. Louis. She eventually started a sex crimes unit within the department. But it was a small department with a tight budget. When she couldn’t get the money she needed, Taylor gave speeches and wrote her own proposals to keep her program operating.

What troubled her was that while the sex crimes unit had to find funding on its own, the SWAT team was always flush with cash. “The SWAT team, the drug guys, they always had money,” Taylor says. “There were always state and federal grants for drug raids. There was always funding through asset forfeiture.” Taylor never quite understood that disparity. “When you think about the collateral effects of a sex crime—of how it can affect an entire family, an entire community—it just didn’t make sense. The drug users weren’t really harming anyone but themselves. Even the dealers, I found much of the time they were just people with little money, just trying to get by.”

The SWAT team eventually co-opted her as a member. As the only woman in the department, she was asked to go along on drug raids in the event there were any children inside. “The perimeter team would go in first. They’d throw all of the adults on the floor until they had secured the building. Sometimes the kids too. Then they’d put the kids in a room by themselves and the search team would go in. They’d come to me, point to where the kids were and say, ‘You deal with them.’ ” Taylor would then stay with the children until family services arrived, at which point they’d be placed with a relative.

Taylor’s moment of clarity came during a raid on an autumn evening in November 2000. Narcotics investigators had made a controlled drug buy a few hours earlier and were laying plans to raid the suspect’s home. “The drug buy was in town, not at the home,” Taylor says. “But they’d always raid the house anyway. They could never just arrest the guy on the street. They always had to kick down doors.”

With just three hours between the drug buy and the raid, the police hadn’t done much surveillance at all. The SWAT team would often avoid raiding a house if they knew there were children inside, but Taylor was troubled by how little effort they put into seeking out that sort of information. “Three hours is nowhere near enough time to investigate your suspect, to find out who might be inside the house. It just isn’t enough time for you to know the range of things that could happen.”

That afternoon the police had bought drugs from the stepfather of two children, ages 8 and 6. Both were in the house at the time of the raid. The stepfather wasn’t.

“They did their thing,” Taylor says. “Everybody on the floor, guns and yelling. Then they put the two kids in the bedroom, did their search, then sent me in to take care of the kids.”

Taylor made her way inside to see them. When she opened the door, the 8-year-old girl assumed a defense posture, putting herself between Taylor and her little brother. She looked at Taylor and said, half fearful, half angry, “What are you going to do to us?”

Taylor was shattered. “Here I come in with all my SWAT gear on, dressed in armor from head to toe, and this little girl looks up at me, and her only thought is to defend her little brother. I thought, ‘How can we be the good guys when we come into the house looking like this, screaming and pointing guns at the people they love? How can we be the good guys when a little girl looks up at me and wants to fight me? And for what? What were we accomplishing with all of this? Absolutely nothing.’ “

Taylor was later appointed police chief of the small town of Winfield, Mo. Winfield was too small for its own SWAT team, even in the 2000s, but Taylor says she’d have quit before she ever created one. “Good police work has nothing to do with dressing up in black and breaking into houses in the middle of the night. And the mentality changes when they get put on the SWAT team. I remember a guy I was good friends with; it just completely changed him. The us-versus-them mentality takes over. You see that mentality in regular patrol officers too. But it’s much, much worse on the SWAT team. They’re more concerned with the drugs than they are with innocent bystanders. Because when you get into that mentality, there are no innocent people. There’s us and there’s the enemy. Children and dogs are always the easiest casualties.”

Taylor recently ran into the little girl who changed the way she thought about policing. Now in her 20s, the girl told Taylor that she and her brother had nightmares for years after the raid. They slept in the same bed until the boy was 11. “That was a difficult day at work for me,” she says. “But for her, this was the most traumatic, defining moment of this girl’s life. Do you know what we found? We didn’t find any weapons. No big drug operation. We found three joints and a pipe.”

AP Photo/NTCK UT

FUNDING THE FLAME

By the mid-1990s, the Byrne Formula Grant Program that Congress had started in 1988 had pushed police departments across the country to prioritize drug crimes over other investigations. When applying for grants, departments are rewarded with funding for statistics such as the number of overall arrests, the number of warrants served or the number of drug seizures. Those priorities, then, are passed down to police officers themselves and are reflected in how they’re evaluated, reviewed and promoted.

Perversely, actual success in reducing crime is generally not rewarded with federal money, on the presumption that the money ought to go where it’s most needed—high-crime areas. So the grants reward police departments for making lots of easy arrests (i.e., low-level drug offenders) and lots of seizures (regardless of size) and for serving lots of warrants. When it comes to tapping into federal funds, whether any of that actually reduces crime or makes the community safer is irrelevant—and in fact, successfully fighting crime could hurt a department’s ability to rake in federal money.

But the most harmful product of the Byrne grant program may be its creation of hundreds of regional and multijurisdictional narcotics task forces. That term—narcotics task force—pops up frequently in case studies and horror stories. There’s a reason for that. While the Reagan and [first] Bush administrations had set up a number of drug task forces in border zones, the Byrne grant program established similar task forces all across the country. They seemed particularly likely to pop up in rural areas that didn’t yet have a paramilitary police team (what few were left).

The task forces are staffed with local cops drawn from the police agencies in the jurisdictions where the task force operates. Some squads loosely report to a state law enforcement agency, but oversight tends to be minimal to nonexistent. Because their funding comes from the federal government—and whatever asset forfeiture proceeds they reap from their investigations—local officials can’t even control them by cutting their budget. This organizational structure makes some task forces virtually unaccountable, and certainly not accountable to any public official in the region they cover.

As a result, we have roving squads of drug cops loaded with SWAT gear who get more money if they conduct more raids, make more arrests and seize more property, and they are virtually immune to accountability if they get out of line. In 2009 the U.S. Department of Justice attempted a cost-benefit analysis of these task forces but couldn’t even get to the point of crunching the numbers. The task forces weren’t producing any numbers to crunch. “Not only were data insufficient to estimate what task forces accomplished,” the report read, “data were inadequate to even tell what the task forces did for routine work.”

Not surprisingly, the proliferation of heavily armed task forces that have little accountability and are rewarded for making lots of busts has resulted in some abuse.

iStockPhoto

THE TULIA RAID

The most notorious scandal involving these task forces came in the form of a massive drug sting in the town of Tulia, Texas. On July 23, 1999, the task force donned black ski-mask caps and full SWAT gear to conduct a series of coordinated predawn raids across Tulia. By 4 a.m., six white people and 40 blacks—10 percent of Tulia’s black population—were in handcuffs. The Tulia Sentinel declared: “We do not like these scumbags doing business in our town. [They are] a cancer in our community; it’s time to give them a major dose of chemotherapy behind bars.” The paper followed up with the headline “Tulia’s Streets Cleared of Garbage.”

The raids were based on the investigative work of Tom Coleman, a sort of freelance cop who, it would later be revealed, had simply invented drug transactions that had never occurred.

The first trials resulted in convictions—based entirely on the credibility of Coleman. The defendants received long sentences. For those who were arrested but still awaiting trial, plea bargains that let them avoid prison time began to look attractive, even if they were innocent. Coleman was even named Texas lawman of the year.

But there were some curious details about the raids. For such a large drug bust, the task force hadn’t recovered any actual drugs. Or any weapons, for that matter. And it wasn’t for a lack of looking: The task force cops had all but destroyed the interiors of the homes they raided. Then some cases started falling apart. One woman Coleman claimed sold him drugs could prove she was in Oklahoma City at the time. Coleman had described another woman as six months’ pregnant—she wasn’t. Another suspect could prove he was at work during the alleged drug sale. By 2004, nearly all of the 46 suspects were either cleared or pardoned by Texas Gov. Rick Perry. The jurisdictions the task force served eventually settled a lawsuit with the defendants for $6 million. In 2005 Coleman was convicted of perjury. He received 10 years’ probation and was fined $7,500.

In the following years, there were numerous other corruption scandals, botched raids, sloppy police work, and other allegations of misconduct against the federally funded task forces in Texas. Things got so bad that by the middle of the 2000s Perry began diverting state matching funds away from the task forces to other programs. The cut in funding forced many task forces to shut down. The stream of lawsuits shut down or limited the operations of others. In 2001 the state had 51 federally funded task forces. By the spring of 2006, it was down to 22.

Funding for the Byrne grant program had held steady at about $500 million through most of the Clinton administration. The Bush administration began to pare the program down—to about $170 million by 2008. This was more out of an interest in limiting federal influence on law enforcement than concern for police abuse or drug war excesses.

But the reaction from law enforcement was interesting. In March 2008, Byrne-funded task forces across the country staged a series of coordinated drug raids dubbed Operation Byrne Blitz. The intent was to make a series of large drug seizures to demonstrate how important the Byrne grants were to fighting the drug war. In Kentucky alone, for example, task forces uncovered 23 methamphetamine labs, seized more than 2,400 pounds of marijuana, and arrested 565 people for illegal drug use. Of course, if police in a single state could simply go out and find 23 meth labs and 2,400 pounds of marijuana in 24 hours just to make a political point about drug war funding, that was probably a good indication that 20 years of Byrne grants and four decades of drug warring hadn’t really accomplished much.

During the 2008 presidential campaign, Barack Obama criticized [George W.] Bush and the Republicans for cutting Byrne, a federal police program beloved by his running mate Joe Biden. Despite Tulia … and a growing pile of bodies from botched drug raids, and the objections of groups as diverse as the ACLU, the Heritage Foundation, La Raza and the Cato Institute, Obama promised to restore full funding to the program, which, he said, “has been critical to creating the anti-gang and anti-drug task forces our communities need.”

He kept his promise. The 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act resuscitated the Byrne grants with a whopping $2 billion infusion, by far the largest budget in the program’s 20-year history.

9/11 OPENS A SPIGOT

Police militarization would accelerate in the 2000s. The first half of the decade brought a new and lucrative source of funding and equipment: homeland security. In response to the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, on the World Trade Center in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, the federal government opened a new spigot of funding in the name of fighting terrorism. Terrorism would also provide new excuses for police agencies across the country to build up their arsenals and for yet smaller towns to start up yet more SWAT teams.

The second half of the decade also saw more mission creep for SWAT teams and more pronounced militarization, even outside of drug policing. The 1990s trend of government officials using paramilitary tactics and heavy-handed force to make political statements or to make an example of certain classes of nonviolent offenders would continue, especially in response to political protests. The battle gear and aggressive policing would also start to move into more mundane crimes—SWAT teams have recently been used even for regulatory inspections.

But the last few years have also seen some trends that could spur some movement toward reform. Technological advances in personal electronic devices have armed a large percentage of the public with the power to hold police more accountable with video and audio recordings. The rise of social media has enabled citizens to get accounts of police abuses out and quickly disseminated. This has led to more widespread coverage of botched raids and spread awareness of how, how often and for what purpose this sort of force is being used.

Over just the last six years, media accounts of drug raids have become less deferential to police. Reporters have become more willing to ask questions about the appropriateness of police tactics and more likely to look at how a given raid fits into broader policing trends, both locally and nationally. Internet commenters on articles about incidents in which police may have used excessive force also seem to have grown more skeptical about police actions, particularly in botched drug raids.

It’s taken nearly a half-century to get from those Supreme Court decisions [upholding questionable searches and police tactics] in the mid-1960s to where we are today—police militarization has happened gradually, over decades. We tend not to take notice of such long-developing trends, even when they directly affect us. The first and perhaps largest barrier to halting police militarization has probably been awareness. And that at least seems to be changing.

Whether it leads to any substantive change may be the theme of the current decade.

Sidebar

Warring Against Crime

In a remarkable speech at the National Defense University in May, President Barack Obama signaled an end to the war on terrorism; maybe not an end, it turns out, but a winding down of the costly deployments, the wholesale use of drone warfare, and even the very rhetoric of war.

Prompted by the odious attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C., in 2001, he said, we took the battle, for better or worse, to Afghanistan and to Iraq and, surreptitiously, to Pakistan to punish those deemed responsible. We moved on the home front, as well; perhaps too quickly, some would argue—“hardening targets, tightening transportation security, giving law enforcement new tools to prevent terror,” as the president described the domestic defense agenda.

Some of this hardening and tightening was obvious. Surveillance cameras be-came as ubiquitous as concrete barriers. Office buildings tightened security. Passengers were screened for weapons before boarding planes. But in local law enforcement some of the “new tools” made available to even the smallest police departments helped accelerate changes in policing, changes that some say altered the way police departments behave.

Today, police departments—or some of their key enforcement operations—appear to be on a war footing. Many dress in commando black, instead of the traditional blue. They own military-grade weapons, armored personnel carriers, helicopters and Humvees. Their training is military. Their approach is military. They are in a war against crime and violence and terror that they argue never ends. Just ask those at the finish line of the Boston Marathon on April 15.

In his new book, Rise of the Warrior Cop, journalist Radley Balko points out that this militarization of police departments had taken hold several decades before 9/11. He argues, in the following excerpt, that a few appropriate applications of those tactics and weaponry have obscured their routine use each day, against U.S. citizens accused of ordinary crimes, in ways that would have been repugnant to the nation’s founders. “To say a military tactic is legal, or even effective, is not to say it is wise or moral in every instance,” the president noted in his recent speech. “For the same human progress that gives us the technology to strike half a world away also demands the discipline to constrain that power—or risk abusing it.”

Whether or not you agree with him, it is an issue that Balko has been chronicling for years at the local and national levels. And in this particular moment of national introspection about the efficacy of traditional warfare against the threat of determined terrorists, Balko poses the question about its efficacy against common crime.

—The Editors

Radley Balko is an investigative journalist who writes about civil liberties, police, prosecutors and the broader criminal justice system. He is a senior writer for the Huffington Post.