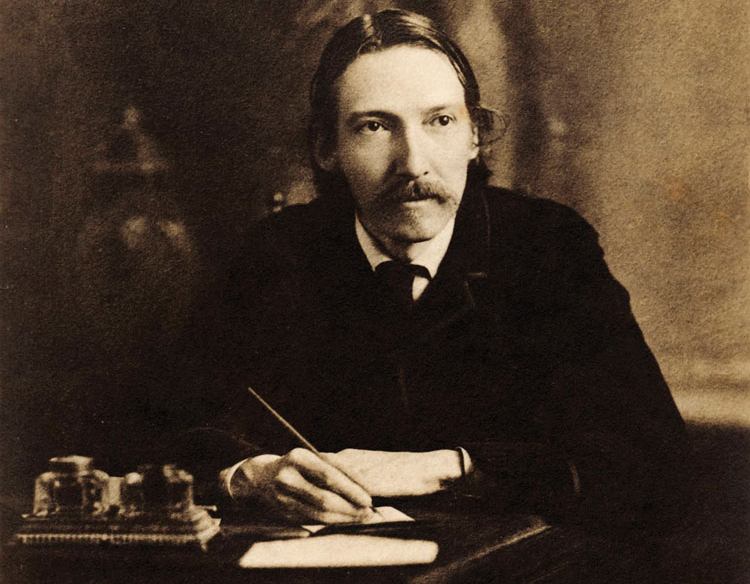

Some posthumous wisdom on writing from Robert Louis Stevenson

Photo courtesy of Culture Club/Contributor

Readers of this column know that I occasionally sit down to interview long-dead authors. I do it not by time traveling but by consulting their works published long ago and asking questions as I read.

This month’s interviewee is the esteemed Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894), the Scottish writer famous mainly for his novels Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Stevenson traveled the world and spent a great deal of time in the United States. At the age of 30, he spent a summer honeymooning at an abandoned mining camp at Mount Saint Helena in California. He was obviously a romantic. The place he stayed is now called Robert Louis Stevenson State Park.

On a Thursday in mid-July, we sat down for an agreeable chat. I was astonished, frankly, at his candor and amiability. The words in his answers are drawn from a posthumous collection of his essays titled Learning to Write (1920).

Garner: How did you become a writer?

Stevenson: All through my boyhood and youth, I was always busy trying to learn to write. I had vowed that I would learn to write. That was a proficiency that tempted me; and I practiced to acquire it, as men learn to whittle, in a wager with myself.

Garner: How did you start?

Stevenson: Description was the principal field of my exercise; for to anyone with senses there is always something worth describing, and town and country are but one continuous subject. But I worked in other ways also. I often accompanied my walks with dramatic dialogues in which I played many parts and often exercised myself in writing down conversations from memory.

Garner: That’s how you learned?

Stevenson: No, that wasn’t the most efficient part of my training. Good though it was, it only taught me, so far as I have learned them at all, the lower and less intellectual elements of the art—the choice of the essential note and the right word. It set me no standard of achievement. So there was perhaps more profit, as there was certainly more effort, in my secret labors at home.

Garner: Secret labors? Sounds mysterious.

Stevenson: Whenever I read a book or a passage that particularly pleased me, in which a thing was said or an effect rendered with propriety, in which there was either some conspicuous force or some happy distinction in style, I must sit down at once and set myself to ape that quality. I was unsuccessful and I knew it, and tried again, and was again unsuccessful and always unsuccessful; but at least in these vain bouts, I got some practice in rhythm, in harmony, in construction and the coordination of parts. I played the sedulous ape.

Garner: That’s how David Foster Wallace taught himself to write.

Stevenson: That, like it or not, is the way to learn to write; whether I have profited or not, that is the way. It was the way Keats learned, and there was never a finer temperament for literature than Keats’; it was so, if we could trace it out, that all people have learned; and that is why a revival of letters is always accompanied or heralded by a cast back to earlier and fresher models.

Garner: Doesn’t sound very original.

Stevenson: It is not the way to be original! It isn’t. Nor is there any way but to be born so. Nor yet, if you are born original, is there anything in this training that shall clip the wings of your originality. There can be none more original than Montaigne; neither could any be more unlike Cicero. Yet no craftsman can fail to see how much the one must have tried in his time to imitate the other. It is only from a school that we can expect to have good writers; it is almost invariably from a school that great writers, these lawless exceptions, come. Nor is there anything here that should astonish the considerate. Before he can tell what cadences he truly prefers, the student should have tried all that are possible. Before he can choose and preserve a fitting key of words, he should long have practiced the literary scales; and it is only after years of such gymnastics that he can sit down at last, legions of words swarming to his call, dozens of turns of phrase simultaneously bidding for his choice, and he himself knowing what he wants to do and—within the narrow limit of a man’s ability—able to do it.

Bryan A. Garner, editor-in-chief of Black’s Law Dictionary and author of many books on advocacy and legal drafting, is the distinguished research professor of law at Southern Methodist University. His most recent book is Nino and Me: My Unusual Friendship with Justice Antonin Scalia. Follow on Twitter @BryanAGarner. This article was published in the September 2018 ABA Journal magazine with the title “An interview with Robert Louis Stevenson: Some posthumous wisdom on writing from one of the masters.”