Extreme sports are more popular than ever, prompting questions about legal liability

Tough Mudder events include obstacles called Fire in Your Hole, Arctic Enema and Berlin Walls. Photo by Bruce Bennett/Getty Images.

Last year in West Virginia, 28-year-old Avishek Sengupta was running the Tough Mudder, a grueling 10-plus-mile race littered with merciless obstacles that take participants over blazing pits of fire, through dark trenches and into pools of water laced with electrical wires that deliver 10,000 volts.

When Sengupta approached the obstacle called Walk the Plank—a 12-foot-high wooden structure with a pool of chocolate-brown, muddy water below—he plunged in along with the throngs of racers. But unlike the others, he didn’t immediately come up.

Nearly 15 minutes passed before he finally surfaced in the arms of a rescue diver, foaming at the mouth, according to news reports. Sengupta died in a hospital the next day.

Now his family has retained counsel in preparation for a lawsuit against Tough Mudder, whose spokeswoman declined to comment.

Tough Mudder, calling itself “Probably the Toughest Event on the Planet,” is run by a Brooklyn-based company that is one of a growing number catering to the booming industry of obstacle course racing. As sports enthusiasts and adrenaline junkies hunt for ever-more-hardcore events to test their physical limits, it’s a pastime that has gained popularity in the past five years.

But as the sport gains traction, it is also testing the limits of the law. As in most extreme sports, obstacle course racers are required to sign liability waivers. But unlike in other sports, the inherent risks aren’t always obvious; indeed, they are often intentionally magnified to titillate participants and crowds. This pushes the new sport somewhat outside the traditional framework of negligence and assumption of risk.

“The whole point of an obstacle course race is to in fact come up with all these inherent dangers and risks,” says David Horton, acting professor at the University of California at Davis School of Law, who has written about extreme sports and risk. “That makes it very difficult to fit within our existing paradigms. We tend to think of risks as being an unfortunate byproduct of things like traditional sports, but for something like Tough Mudder the risk is the purpose of the event.”

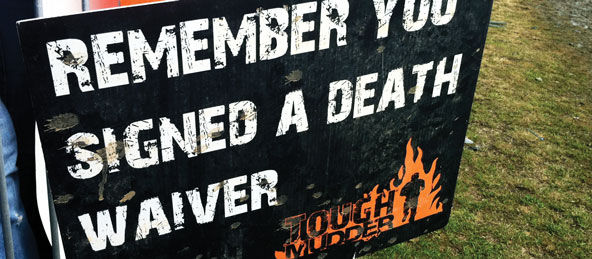

Indeed, Tough Mudder racers often brag about having “survived” the event after signing what they like to call the “death waiver,” essentially a catchy phrase for any liability waiver that encompasses death. Obstacle course racing companies routinely tout the fact that participants could die during their event, upping the ante for thrill-seekers. Tough Mudder famously displays signs that read “Remember, you signed a death waiver” along some stretches of its courses.

But critics argue that the waivers don’t adequately disclose the full panoply of dangers, and that many of the obstacles are made unnecessarily perilous.

“Lines have to be drawn between what the participants are signing up for and what they’re actually getting,” says Sengupta’s attorney, Robert J. Gilbert of the Andover, Mass.-based firm Gilbert & Renton. “Participants sign up for the challenge, but it’s less clear that they sign up for the dangers—particularly the undisclosed dangers or gratuitous dangers.”

Courtesy Tough Mudder

NOTHING NEW UNDER THE SUN

High-risk sporting events have been around for ages, with the gladiator matches of the Roman era being a fabled example. Each decade the advent of a new extreme sport raises the standard of what is perceived as risky or dangerous. It used to be in the 1970s that running a marathon was extreme; now completing a marathon is for the masses. Then the triathlon became the new extreme, followed by countless other activities, such as heli-skiing, volcano surfing, wingsuit flying and BASE jumping. There is even a newly emerging American sport inspired by Spain’s running of the bulls.

Television has played its role in increasing the popularity of these sports with shows such as World of X Games and the Extreme Sports Channel. Energy drink company Red Bull has also been on the forefront of the extreme sports movement, with events like the Red Bull Cavemen triathlon, which involves running, mountain biking and kayaking, and the Red Bull Stratos, a space-diving event that in October 2012 featured a skydiver who jumped from nearly 130,000 feet.

At the same time, there’s been a rise in so-called functional fitness—exercises that replicate actual human actions rather than simulated exercises. This has led more athletes to participate in boot-camp-like sports such as CrossFit, which involves challenges like climbing a rope or pulling a tractor tire.

These two trends—extreme sports and functional fitness—have collided in the obstacle course racing craze. Today there are dozens of companies that put on these endurance events, the most popular of which is the Tough Mudder, followed by the Spartan Race and the Warrior Dash. There are also a series of smaller races put on by local organizers around the world.

The growth has been staggering. Tough Mudder put on 35 events with more than 460,000 participants in 2012, up from just three events with 20,000 participants in 2010, according to the company’s website. Also, there’s a brand-new association just for the sport, called the Obstacle Racing Association.

Meanwhile, the sport is becoming big business. With more than 1.5 million participants nationwide, and each often paying upwards of $100 to run the race, organizers are cashing in. The three big companies—Tough Mudder LLC, Red Frog Events (Warrior Dash) and Spartan Race—raked in a combined $150 million at least in 2012, according to Outside magazine.

A Tough Mudder competitor takes on the Kiss of Mud obstacle in Englishtown, N.J. Photo by Bruce Bennett/Getty Images.

THE THRILL OF DEFEAT

While Sengupta’s death is the first for Tough Mudder, it isn’t the first death or serious injury for the industry as a whole. In recent years a man drowned while running an obstacle course race in Fort Worth, Texas; another two were paralyzed at separate events; there have been several cases involving lacerations, burns, dehydration, hypothermia and heatstroke.

A November article in the Annals of Emergency Medicine described a single weekend last year in which a Pennsylvania hospital received 38 emergency patients from a Tough Mudder event, including several who suffered electrical injuries.

“The burden on EMS during this event was unanticipated,” reads the article. “Reportedly, more than 100 advanced life support responses were activated, with many patients receiving initial treatment and then refusing transport. As observed by the diversity and severity of the illness reported, it stands to reason that events such as the Tough Mudder and endurance races like it (e.g., Warrior Dash, Spartan Race) may carry higher inherent risk factors for injury.”

A Tough Mudder competitor runs through curtains of live electrical wires in Merrimac, Wis. Photo by John Hart, AP Photo/Wisconsin State Journal.

This has, not surprisingly, led to a wave of litigation. The family of the man who drowned in the Fort Worth race filed a lawsuit against the race organizer. And a man paralyzed during an obstacle course race who was unregistered and did not sign the liability disclaimer settled a $30 million lawsuit for $300,000.

There’s a fairly well-developed body of case law around extreme sports in general, such as skiing or white-water rafting. Waivers are typically the first line of defense for sports providers. Whether a waiver will be enforced depends on state law and varies widely from state to state. In most states, sport providers are protected from liability when an injury occurs as a result of an “inherent risk” assumed by the participant, such as hitting a tree while skiing, crashing while mountain biking or getting hit by a golf ball on the fairway.

In most states, waivers typically insulate providers from claims arising from ordinary negligence. But there are a handful of states where waivers are generally not enforceable at all as a matter of public policy. Typically, claims aren’t barred in the event of gross negligence or reckless actions even when a waiver is signed. For example, defendants typically cannot escape liability in the event that their conduct in any way increased the risk of the activity, say, purposely shaping a ski jump to be wantonly dangerous or failing to put water stations on a marathon course. Another question pertaining to the enforceability of a waiver is whether the risk could be removed without changing the nature of the activity.

Read example waivers:

- Tough Mudder (PDF)

- Spartan Race (PDF)

- Warrior Dash (PDF)

Current as of May 2014.

Gilbert, Sengupta’s attorney, argues the risks at the West Virginia Tough Mudder were “gratuitous” and could have been eliminated without changing the nature of the event. He points to the water pit under the obstacle where Sengupta’s drowning occurred. It was “made deliberately muddy,” he says. “As a result it was impossible for participants to see if there was somebody down below them before jumping in the water, and it was impossible for lifeguards to determine if somebody was still underwater who had not resurfaced. … There’s nothing about cloudy water that’s essential to the challenge of jumping into water from that height and then swimming out. That could have eliminated the risk.”

He also argues that the plank was “deliberately crowded” in a bid to move participants quickly through the obstacle in response to social media complaints about long lines. In fact, he alleges the race eliminated pre-existing safety measures used at other events, such as putting in lane dividers on the plank that would have made the jump more orderly. Staying within the plank’s capacity, he says, would have materially improved safety without altering the inherent challenge of the obstacle.

“They had a big interest in moving people through quickly,” he says.

Tough Mudder’s website says about that particular obstacle: “Test your fear of heights with this 12-foot-high jump into a deep, muddy water pit. Don’t think too much before you leap—you’ll hold up everyone else, and the volunteers at the top of the platform don’t like to babysit Mudders. Unless you want a loud earful from them, you’d better just jump.”

This is where it gets thorny from a legal standpoint, since the essential purpose of the event is to push racers’ personal boundaries by participating in something so dangerous that it borders on sadistic—or outlandish.

“It gets really difficult to figure out what you’re talking about with these new sports,” says Horton from UC Davis. “These assumption-of-risk cases arose in the context of very well-defined sports, like football or soccer. With these new sports there’s just no baseline. What is the inherent risk of slithering through a pool with electrodes?”

The CEO of Tough Mudder, Will Dean, explained it in The New Yorker’s Jan. 27 issue. “What Tough Mudder does well is things that shouldn’t be: I’m running in fire! I’m in a dumpster full of ice! I’m getting zapped with 10,000 volts of electricity! … People want to leave this event with a few cuts and bruises.”

Another event called the Spartan Death Race includes harsh obstacles along a 48-hour course—chopping wood for two hours straight, cutting a bushel of onions or hiking 30 miles with a rock-stuffed backpack.

The Spartan Death Race organizer, Peak Races, says this on its website, which until recently had an address of youmaydie.com: “The Death Race is designed to present you with the totally unexpected, the totally insane, and take you out of your comfort zone. This race is a 48-plus-hour event that is created to break you physically, mentally and emotionally. All of you will enter, 90 percent of you won’t finish. Only consider this race if you have lived a full life to date.”

The New York Times has called the Spartan Death Race “Survivor Meets Jackass.” Photo courtesy of Reebok.

THE BUSINESS OF RISK

It’s unlikely that obstacle racing is in fact more dangerous than some of the other long-standing extreme sports, such as BASE jumping (the acronym stands for the four types of objects that jumpers leap from: buildings, antennas, spans [bridges] and earth). According to an independent University of Oxford journal, it is one of the most deadly sports around, with one in every 2,317 jumps resulting in death; that’s compared to one in about 100,000 deaths for skydiving, one in about 127,000 deaths for marathon running and one in about 1.6 million deaths for skiing.

All the hype and sensationalizing of the risk involved in Tough Mudders and the like could actually insulate race organizers from liability.

In some ways, Horton says, he could see obstacle racing being more defensible than other activities, like BASE jumping, where people aren’t always aware of just how risky the sport is. Race organizers “could argue that they’re doing everything in their power to get self-selected people who truly want to do this.”

Gilbert argues that the obstacle races are sending mixed messages. “On the one hand Tough Mudder holds up signs saying ‘Remember you signed a death waiver’ … while trying to downplay the same risk that they’re encouraging their participants to accept. That leads to questions of fraudulent inducement.”

Waivers have largely stood the test of time in the extreme sports arena. “The waiver has proven to be very, very beneficial in protecting the association and the event organizer,” says Mike Price, president of ESIX Global, an entertainment and sports risk-management firm based in Atlanta. “My feeling is for the larger events like Tough Mudder, I think you’ll probably see pretty good traction for the waivers.”

And Tough Mudder’s waiver doesn’t mince words. Here’s an excerpt: “The Tough Mudder event … is meant to be an extreme test of toughness, strength, stamina, camaraderie and mental grit that takes place in one place in one day. … Venues are part of the challenge and usually involve hostile environments that might include extreme heat or cold, snow, fire, mud, extreme changes in elevation, and water. Some of the activities include runs, military-style obstacles, going through pipes, traversing cargo nets, climbing walls, encountering electric voltage, swimming in cold water, throwing or carrying heavy objects and traversing muddy areas. In summation, the TM event is a hazardous activity that presents the ultimate physical and mental challenge to participants. … Catastrophic injuries are rare; however, we feel that our participants should be aware of the possibility. These injuries can include permanent disabilities, spinal injuries and paralysis, stroke, heart attack, and even death.”

Photo by Andy Cross of the Denver Post via Getty Images

THE AWARENESS PRINCIPLE

Robin Ammon, an associate professor of kinesiology and sport science at the University of South Dakota, says it’s incumbent on participants to know ahead of time what they’re signing up for, and to use common sense on the course, including bypassing any obstacle that seems too difficult.

“There are inherent risks to any kind of activity that you’re involved in,” he says. “Individuals that are going through these need to be well aware of what they are. … Don’t dive head first into a water pit. A lot of times these things are only 3 feet deep and you can blow out a cervical vertebra.”

Ammon, who has completed a Tough Mudder, also says participants must train properly in advance of the race.

“A lot of it is you have to know yourself, your own personal limitations, and you have to be in the proper shape. You have to have an understanding of what am I getting myself into—the training that I have done. How many people would just say, ‘I’m going to run a marathon tomorrow’?”

What’s unique about obstacle course racing, however, is that it’s not always easy to prepare or train for what the competitors might encounter. For example, while it’s common to train for months or even years to complete the Iron Man’s 2.4-mile swim, 112-mile bicycle ride and 26.2-mile run, it’s hard to train for some of the obstacles racers will encounter in a Tough Mudder.

The Annals of Emergency Medicine article says this: “For a marathon or triathlon, a significant amount of training is involved. In some of these endurance events, effective training may prevent problems such as dehydration or rhabdomyolysis, but it is doubtful that training will enhance performance or prevent injury in an event in which obstacles include having to jump off a 9-foot height or run through a field of electrical wires (while the participant is wet and hot). Training might not have prevented many of the injuries that occurred in this event.”

Also, participants in obstacle course racing aren’t always the strong or elite athletes generally found in other extreme sports. Many of them are thrill-seekers rather than seasoned competitors. This could exacerbate the risk factor for many participants who perhaps underestimate the physical prowess needed to actually complete one of these races.

A fire jump obstacle has been part of almost every incarnation of the Spartan Race. Photo courtesy of Reebok.

WILL INDUSTRY STANDARDS HELP?

Part of the problem in the obstacle course racing industry is there are no fully developed, industrywide standards, although the newly formed Obstacle Racing Association could fill this void.

“Some are very good operators; some are not,” says risk-management executive Price. “Without a governing body to regulate it, these standards are all over the place. You can have an event that has perfect EMT setups and doctors and nurses, while at another one the only thing that they’ll have is a number to call for an EMT. The fluctuation in the standard is so vast right now in this sport, which makes it potentially risky.”

It’s natural to have a series of unanswered questions surrounding this sport, Price says. In fact, many of the most established sports have gone through this type of evolution.

“There’s an initial surge of grassroots interest and then all of a sudden others enter the marketplace and see the business opportunity,” he says. “That leads to a vast and quick explosion of new players entering the market with maybe not as much attention to risk management and safety just to make a quick buck.”

Eventually, he says, the pendulum swings the other way once the lawsuits start flowing in, forcing organizers to develop standards to survive as a sport.

“Typically there’s a lag between the evolution of the industry and those claims,” says Price. “Claims take time to go through the process. It feels like, in our opinion, that we’re at the front end of that wave of claims and lawsuits that really are going to dictate change.”

Also sure to play a role in shaping the future of the nascent sport are the insurers.

From a risk management standpoint, insurers will increasingly seek changes to mitigate risks. That means race organizers will have to figure out how to maintain the culture and appeal of the sport while instilling a standard of safety and risk management acceptable to insurers.

This could be difficult. For example, a lot of these races, which are often located near college campuses, have alcohol woven into their culture, which poses another risk management challenge.

“Insurance carriers will tell you they feel like a frat party with an obstacle race as a warm-up,” Price says. Indeed, the Tough Mudder touts this: “After dropping your fair share of F-bombs, you cross the finish line. You’re greeted with an orange headband, a high-five and a Dos Equis beer.”

Also, some of the obstacles may increasingly seem just too risky. For example, Price says, what if somebody with a pacemaker goes through the electrical shock obstacle and ends up having a heart attack? Or somebody wearing excessive clothing jumps over the fire pits and goes up in flames?

“As soon as these claims hit, insurance carriers will not write this coverage because of the known potential danger,” he says.

So if you’re dying to run a truly tough Tough Mudder or other obstacle course race, you’d better do it soon because Price’s prediction is that “fire pits, electrical shocks—all of these things, in my opinion—will be gone from this sport in a few years.”

This article originally appeared in the June 2014 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “The Few, the Proud, the Extreme: Extreme recreational sports are more popular than ever, bringing with them growing numbers of injuries and deaths.”

Lauren Etter is a freelance journalist based in Chicago.