Employers and workers grapple with laws allowing marijuana use

Illustration by Stephen Webster

When the state's residents passed a referendum in 2012 legalizing recreational marijuana use—long after the state sanctioned medical use in 2000—few had any idea that Coloradans who partook in the bud would end up jeopardizing their livelihood.

That’s exactly what the court permitted in Coats v. Dish Network. The case pitted a quadriplegic licensed to use medical marijuana against his employer. The court held the state’s “lawful activities statute,” which generally prohibits employers from firing employees for engaging in lawful activities off the job, applied only to activities lawful under Colorado and federal law. Because marijuana is illegal under the federal Controlled Substances Act, its use isn’t lawful—and can remain a valid basis for termination in the state.

Coats addressed just one sliver of the universe of employment law issues triggered by the loosening of marijuana laws. There’s an entire galaxy of questions just about how employers must treat marijuana use under state and federal employment laws, including disability laws, to which clear answers have been slow to emerge.

“I think there’s mass confusion,” reports Lori Ecker, a Chicago lawyer who for 32 years has represented employees in workplace disputes and served as a neutral mediator and arbitrator. “The core problem is that marijuana continues to be a Schedule I drug according to federal drug law. That’s the 800-pound gorilla in the room.

“There are laws that protect employees,” she says, “like the Americans with Disabilities Act. Illinois also has a human rights act, and many states have fair employment acts. Illinois is like Colorado in that it also has a law that protects employees’ legal, off-duty conduct. Yet all these acts specifically exclude from disability any employee or applicant who’s currently engaging in the illegal use of drugs.”

Lori Ecker. Photo by Wayne Slezak.

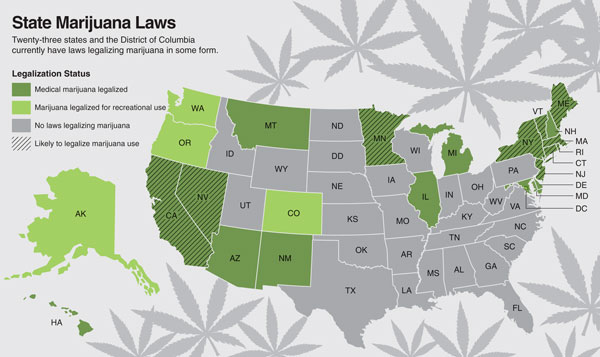

THE LAY OF THE LAND

Marijuana use is now permitted in 23 states and the District of Columbia, according to Governing magazine. Four states—Alaska, Colorado, Oregon, Washington—and the district permit its recreational use. The other 19 states have legalized marijuana use for medical purposes, though their laws vary.

The landscape is changing because support for marijuana legalization has rapidly outgrown opposition, according to the Pew Research Center. In a survey last March, 53 percent of Americans said marijuana should be legal, compared with 44 percent who say it should be illegal. Support for legalization jumped 11 percentage points between 2010 and 2013, and it has remained stable since, Pew reports.

But states that have eased marijuana laws haven’t provided much guidance on the employment front. Connecticut, Illinois, Maine and Rhode Island are among the few that have passed laws protecting medical marijuana patients from employment discrimination on the basis of their pot use, according to James M. Shore, a Seattle-based partner at Stoel Rives who represents employers. Arizona and Delaware bar employers from discriminating against registered medical marijuana patients, including those who have been found to have the drug in their system, unless they use or possess marijuana or are under its influence on the job during work hours. Other states, like Colorado, have statutes prohibiting employers from taking adverse action against employees for engaging in lawful activities off the job.

But then there’s Coats.

The feds are having none of this laid-back treatment of marijuana. The plant has long been classified a Schedule I drug—along with heroin, LSD and Ecstasy—which means it has no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.

Other federal laws compel employers to prohibit the use of marijuana on the job, says Jonathan Sigel, a partner at Mirick, O’Connell, DeMallie & Lougee in Westborough, Massachusetts. President Ronald Reagan issued an executive order in 1986 creating a federal drug-free workplace. In addition, the Drug-Free Workplace Act of 1988 requires employers to maintain a no-drugs environment in order to become a federal contractor or receive federal funding. The upshot: Federal employees and employees of companies that work with the federal government may be terminated for drug use.

DAZED AND CONFUSED

Thom K. Cope, a partner at Mesch, Clark & Rothschild in Tucson, Arizona, says he gets a question a week from employers on the intersection of marijuana and employment law.

The calls typically fall into one of three categories. One is from employers asking how to proceed when an employee fails a random drug test and then whips out a state-issued card authorizing use of medical marijuana. The second is from employers seeking to hire him to teach their managers how to deal with employees permitted to use medical marijuana.

“The third type of inquiry would be someone who read there are 70,000 people in Arizona who have a medical marijuana card and realize their employees could be in that group,” says Cope. “They say, ‘What do we do?’ “

Todd R. Wulffson. Photo by Purplepoint Business Photography.

Some answers are easy: No state requires employers to permit employees to be under the influence of marijuana on the job, according to Alicia Dearn, founder of Bellatrix, a law firm with offices in St. Louis, San Diego and Riverside, California.

In addition, if the employee is in a safety-sensitive position, employers in many states have a clear path to follow.

“Employers haven’t grasped the out the legislators gave them, and that is to designate certain jobs as safety-sensitive positions,” says Cope of Arizona’s medical marijuana law. “If it’s a safety-sensitive position and you test positive for marijuana, you’re out. You can’t just say a secretary is in a safety-sensitive position, but you can declare some positions safety-sensitive.”

But woe betide the employer with multistate operations who’s now thrust into the maze of different rules in different states.

“In Arizona, you can’t terminate just because of a failed marijuana test,” says Todd R. Wulffson, a partner at Carothers DiSante & Freudenberger in Irvine, California, who represents employers. “You have to find if there’s another issue afoot or if the employee has been prescribed medical marijuana.

“In California, if you fail a drug test, you’re gone,” Wulffson notes. “The state’s Compassionate Use Act doesn’t require employers to accommodate possession, use or influence of marijuana in the workplace. Michigan has a very, very medical-marijuana-friendly environment.

“A lot of states have totally different standards,” Wulffson adds. “Unless you want separate employee handbooks for separate states, that’s why some companies like Dish are saying, ‘We’re going to have zero tolerance.’ That’s legally defensible, but it’s also not getting to what people in that state voted for. People are trying to find the lowest common denominator because it’s too difficult otherwise.”

ASSUMED RISKS

On the employee side, many workers wrongly assume they’re following their state’s law, or they simply think their employer should—and must—butt out. In both situations, their employment may be at risk.

“In Illinois, which has a medical marijuana statute, the problem is that we’ve been very slow in certifying vendors,” Ecker says. “I’ve had people call me because they’ve allegedly been using marijuana for medical purposes, but they haven’t been certified yet. They’re getting tested for drugs, coming up positive and getting terminated. I have nothing to tell them, and I’m convinced that will continue to happen even after people get certified to use medical marijuana. I’m concerned the law really doesn’t provide clear protection for employees.”

Employees are similarly uninformed in California. “I’m telling California employers, ‘Make sure you’re putting all employees on notice,’ ” says Wulffson. “Nobody wants to get blindsided by medical marijuana issues. It invariably happens that an employee is using medical marijuana and a company policy says employees can’t abuse illegal drugs. Nobody bothers to tell the employee that medical marijuana is still an illegal drug.

“That communication breakdown leads to a lot of problems. I’m telling all my clients to make sure they say, ‘For purpose of this policy, medical marijuana is deemed to be an illegal drug, and we will treat it the same way we would alcohol and cocaine.’ “

Union employees may be less likely to face such a surprise. “Marijuana has always been a part of collective bargaining,” says Mike McCarthy, a partner at Reid, McCarthy, Ballew & Leahy in Seattle, who represents unions. “But in Washington, the bargaining now comes from a different perspective, mainly that marijuana use is now an entirely legal activity.

“It used to be assumed that testing, for example, for marijuana was well-accepted and going to be done. I don’t think that assumption’s there anymore. It’s more likely to be bargained in more detail about what is and isn’t going to be permissible for employees.”

Most union employees can’t be disciplined or discharged without just cause, McCarthy adds. An increasing number of labor arbitrators are finding that a positive marijuana test that doesn’t indicate impairment at work is insufficient to constitute just cause. McCarthy expects that trend to grow.

“Employers have lost a fallback argument—that although employees weren’t impaired at work, they were doing something illegal,” he says. “I don’t think the fact that marijuana is illegal under federal law is going to be a factor in labor contracts, particularly in private employment.”

AS COLORADO GOES …

A no-exceptions approach was at issue in Colorado’s Coats case. The plaintiff, Brandon Coats, has been a quadriplegic since his teens, according to his lawyer, Michael Evans, who heads a criminal defense firm in Denver. Coats was hired by Dish in 2007 and ranked among the top 5 percent of Dish’s telephone customer service representatives, Evans says.

In 2009, after the painkiller Coats had been using since he was 16 to treat muscle spasms triggered by his condition had lost its effectiveness, his doctor recommended marijuana. Coats got a medical marijuana license and began consuming it at home after work. When Dish conducted a random drug test in May 2010, Coats informed the tester that he would fail but that he had a medical marijuana license.

“It was a yes-or-no test,” says Evans. “It didn’t state the amount of marijuana in Brandon’s system, but Dish admitted he wasn’t using or impaired on the job. Employers say to me, ‘We don’t want impaired employees.’ I’m an employer, too, and that’s not what we’re talking about here.”

Michael Evans. Photo by Jonah Light.

Coats was terminated in June 2010 for violating the company’s drug policy. He sued for wrongful termination, claiming Colorado’s lawful-activities statute prohibited Dish from firing him for engaging in legal off-the-clock activity. The company countered that the state’s medical marijuana law didn’t make medical marijuana use legal; it simply provided users an affirmative defense if they were criminally charged for their actions. Dish also argued that because marijuana was still a Schedule I drug under federal law, Coats’ use didn’t meet the statutory definition of lawful.

The trial court agreed with Dish on both arguments. An appellate court upheld only on the grounds that federal law made marijuana use illegal, leaving for another day the question of whether medical marijuana use is legal under Colorado law. The Colorado Supreme Court also affirmed solely on that basis.

“The recent decision in Colorado is somewhat indicative of the way the law stands right now,” says Joe Yastrow, president of the Laner Muchin law firm in Chicago. “Even though a particular state may have legalized marijuana, either as a recreational drug or for qualifying patients, because it’s still an illegal drug under federal law, the courts—the Colorado decision being indicative—have said you’re not allowed to take your drugs because it’s illegal under federal law.”

Yastrow represents employers exclusively, but he still considers such decisions strange. “I’m not sure the federal law reaches as far as the state decisions interpreting it,” he says. “Federal law tends to be more focused on possession offenses and not someone who’s simply under the influence at a given moment. … It makes no sense that legislators in the states that have passed these laws presumed that, for the purposes of employment, these laws would be immediately nullified by the federal law.”

Nonetheless, many employers are following Dish’s lead. They’re sticking with a zero-tolerance stance and terminating employees found to have used marijuana for whatever reason. Shore of Seattle says he’s seeing employers stick to marijuana prohibitions in part because it appears to make managing employees simpler.

“There are employers that want to maintain zero tolerance either because they’re compelled to under a customer contract or safety regulation,” he says, “or they want to because it’s easier, and you don’t have to get into whether somebody is impaired and whether use was at or off work.”

Chart by Sam Ward

ZERO TOLERANCE FOR DISABILITIES?

However, there’s a risk for employers that retain strict marijuana bans: They may land in the tangle of disabilities laws. Wulffson is currently involved in a half-dozen marijuana-related lawsuits on behalf of his clients, and most involve disabilities accommodation or wrongful discharge claims relating to the failure to accommodate.

Some employers are stumbling into disability lawsuits because they haven’t trained their managers to effectively field unexpected discussions about marijuana use, says Wulffson. A common scenario involves a potential employee who says in an interview: “Just so you know, I have glaucoma and every once in a while I have to self-medicate with marijuana. You’ll accommodate that, right?”

Instead of asking for more information, interviewers typically regurgitate the company’s anti-drug policy, which is a mistake.

“Is the applicant saying she’ll possess, use or smoke at work?” Wulffson asks. “I don’t know. But probably not. The right answer from the manager is: ‘We’ll do everything we can to reasonably accommodate your condition at work. If you need to leave at 2 p.m. to go home to self-medicate or work different hours, that’s fine. But you can’t be under the influence at work.’ “

Managers also need training on the proper ways to use information on marijuana use gathered from social media. After making a job offer, says Wulffson, California employers can do a background check, including checking social media, if they get the applicant’s consent. However, many managers routinely do it at various stages of hiring, and they end up basing hiring decisions on improper factors they’ve gleaned from quick online searches.

Maybe an applicant has posted a picture of himself at a rally to legalize recreational marijuana. But what’s also apparent from the post is that the applicant is in a wheelchair. If the manager declines to hire that applicant, is it because she thinks the applicant is a stoner or because of a perceived disability?

“Employers see medical marijuana as a huge liability mess, and they don’t want to be involved at all,” Wulffson says. “A lot of people are prescreening applicants. That’s actually creating a ton of potential liability because people who are doing the background checks internally aren’t doing them consistently.”

Liability is magnified, he adds, when managers make disciplinary or firing decisions based on social media snapshots.

Perhaps an employee is coming in tired on Mondays and leaving early on Fridays. “You see on Facebook the employee spent all weekend at a rave and was smoking a joint that makes Cheech and Chong jealous,” says Wulffson. “What you don’t know is that he has untreatable cancer, and you may have fired him illegally. And did you also check the social media pages of every other employee doing the same things? I’ve dealt with this a lot.”

Dearn also is wary of employers tripping into disability claims. “In my formative years as an attorney, I second-chaired a disability discrimination trial involving an employer who terminated someone who didn’t come to work for three years—and the employer still got nailed,” she says. “Disabilities laws are expanding, and employers can get hit hard.”

Dearn’s advice to her clients? Tread lightly. If they see employees acting in a way that indicates impairment or that raises safety concerns, don’t accuse them of being under the influence or ask about their medical condition. Instead, Dearn advises employers to pull employees aside and ask them to get clearance from their doctor to perform their work duties; in the meantime, she advises employers to put employees on paid leave.

Wherever possible, Dearn also recommends employers negotiate workarounds for employees using medical marijuana. Her San Diego office sits amid many federal defense contractors that drug-test their employees. They’re worried they’ll face an increase in lawsuits because they’re enforcing drug-free workplace rules required by the U.S. Department of Defense.

Dearn is advising them to continue to enforce their policies and deal with situations on a case-by-case basis. Resolutions have included moving an employee from a position covered by a defense contract to one not covered and working with an employee’s doctor to find an alternative painkiller that’s not illegal under federal law.

LIVE AND LET LIVE

Not all employers are taking the just-say-no approach. Some are rethinking their policies and considering ditching their marijuana bans altogether.

Liza Getches, a partner and chair of the employment law group at Moye White in Denver, has advised against dropping the bans for a host of reasons, not the least of which is that employers would be condoning behavior her state’s highest court has deemed unlawful.

“I’ve had employers call and say, ‘I know so-and-so is doing this for their cancer treatment’ or ‘They have a bad back. I don’t want to test them because I don’t really have a huge problem with them doing it. But I have this policy in place that says they can’t do it. Should I take the policy away?’ ” she says.

“I think it makes a bigger statement to take a policy away that says you can’t use drugs,” Getches says in explanation of her opposition. “In addition, if you don’t want to find out someone’s using marijuana or alcohol, one way to do that is to not test. But there are a lot of risks associated with that. What if someone gets injured on the job or while operating your company’s equipment, and you said you were going to test but didn’t?”

Thom Cope. Photo by Bob Torrez.

One of Sigel’s clients is a manufacturer that employs temporary workers in safety-sensitive positions. Its plan was to hire some of those temps as employees—yet it knew some smoked marijuana recreationally.

“The client said it doesn’t want to lose good people, and if they’re smoking pot on the weekend and it’s not affecting their ability to do their job, they’d like to not include marijuana in the panel of drugs in the pre-employment test,” he explains.

Sigel’s concern was that the positions were safety-sensitive. So the client opted to continue its pre-employment testing and tell employees they’d be subject to random testing. It would provide a one-time warning to employees who tested positive for marijuana. A second positive test would trigger termination.

“That’s different than saying, ‘We’re cool with you smoking on weekends and at night, as long as it’s not at work,’ ” explains Sigel.

Another option for employers is to test employees only when there is suspicion they are impaired. Shore says he’s starting to get calls from employers who want to determine whether they can move from a zero-tolerance to an impairment standard.

“If you’re looking to hire 100 artists or Web designers, that’s different from hiring 100 people who are going to work on machines that could harm their hands if they’re injured,” he says. “Some employers in rural areas with nonsafety jobs may also want to shift their policies because they’d have a hard time finding someone otherwise.”

There are several challenges with testing based on suspicions. The National Institute on Drug Abuse has not set a standard identifying the amount of tetrahydrocannabinol (the active component of marijuana) for a finding that a person is under the influence of marijuana. And even if it had, employers don’t have to follow that standard; they can simply do a pass-or-fail test indicating the presence of THC, as Dish did in Coats.

That’s why Wulffson has such a problem with Coats. If one of Wulffson’s employer clients were faced with similar facts, he’d have advised the client to try very hard to accommodate such an employee, rather than putting before a jury a plaintiff in a wheelchair whom both sides stipulated wasn’t under the influence on the job. “No way I’d let my client do that,” he says.

Wulffson would have tried to work out an agreement, preferably through the employee’s doctor, to impose a threshold of, say, 50 nanograms per milliliter of THC as the baseline for any future drug test. That’s the threshold most often used in California.

“If tests show more than that, the employee would fail,” he says. “That way you don’t end up creating a system where Brandon Coats gets stigmatized and individualized.”

SMOKE ‘EM IF YOU GOT ‘EM

Then there are the employers that simply don’t care if their employees are using pot—and even encourage its use on the job.

“It’s a fringe issue and one I think will become more of an issue in the future,” says Getches. “Some employers have called and said, ‘What if I don’t care if employees smoke?’ “

One was in the landscaping business and another was a design company. Getches advised against telling employees that it’s OK to come to work under the influence of marijuana.

“I know of employers who’ve given out some form of marijuana as a Christmas gift to employees,” she says. “I’m like: ‘I’m not listening!’

“But say an employer wants to give out bottles of wine, or they give whatever they may choose to give out, such as marijuana. The same problems that happen with alcohol also apply to marijuana. An employee does a bong hit, gets in the car and has an accident—you’re liable for the injuries or damages.”

Liza Getches. Photo by Purplepoint Business Photography.

Getches also has concerns about where permissive marijuana policies will lead employers. “I think policies that take away the prohibition of zero tolerance or explicitly state employees can do this if they have something like cancer will swallow the rule,” she says. “I’m sure if I went to my doctor and said my knees hurt, I could get a medical marijuana prescription. Before you know it, everybody’s high at work.”

Wulffson is currently dealing with the fallout of a software developer client’s policy permitting employees to be stoned on the job—a sexual harassment claim. “The company tolerated use of marijuana on the job, and this guy was extraordinarily under the influence,” he explains. “A woman walked into the workspace, and he thought she had nice legs. In a normal context, he’d have kept that thought to himself. Under the influence, he made a comment about what he’d like to do with her on the couch.”

Those risks dramatically outweigh the benefits of permitting marijuana use in the workplace, Wulffson contends. “Whether employees drive their car into a family of four after having smoked a joint in the workplace or whatever the issue, the employer is going to be held liable for knowingly tolerating marijuana use,” he says. “I tell employers: If you want to allow marijuana use, have employees using it work remotely.”

It’s impossible to predict whether more employers will embrace marijuana use on or off the clock. But Laner Muchin’s Yastrow expects the fog among employers and employees to persist. “As attitudes continue to change—both societal and scientific—along with the laws, you’ll see changes in policy, and you’ll also see more legal challenges,” he says. “It’s not completely unlike gay marriage or discrimination against gays, because societal awareness has changed.

“Marijuana isn’t the evil weed anymore, and it can be used as a medicine under the proper controls,” Yastrow says. “My mother-in-law lives in Colorado. She’s 82 years old and pretty damn healthy, but she has terrible insomnia. After trying everything available, she now swears by her pot brownie every evening. If she were taking a mild sedative every night, it would be no problem. But if she were to apply for a job in a lot of states, she’d get bounced.”

This article originally appeared in the December 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Weed-Whacked: Employers and workers grapple with laws permitting recreational and medical marijuana use.”

G.M. Filisko is a lawyer and freelance journalist in Chicago.