Did litigation kill the Beatles?

Poll: Which Beatles cover rocks?

Copies of the May 2016 ABA Journal may be one of the Beatles’ rarities: The print magazine was published with two different covers. One has portraits of the Fab Four in Carnaby Street collarless suits. The flip side is a turntable playing a scratched Beatles LP. (Both are available from the ABA Store).

Which cover do you prefer?

Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, George Harrison and John Lennon made their live television debut in the U.S. on The Ed Sullivan Show on Feb. 9, 1964. Photograph by CBS via Getty Images.

Brian Epstein was a Liverpool record store operator before he became the Beatles’ first full-time manager. His experience in the retail end of the business gave him a clear vision of how he wanted the group to look and act to attract a widespread audience. But with no prior experience as an artist manager, Epstein and his management firm, NEMS Enterprises, were quickly overwhelmed by the complexities of representing an act of such unprecedented popularity as the Beatles. As NEMS executive Tony Bramwell put it, Epstein “flounder[ed] all the way to the top.”

Some of the criticism seems unfair. Beatles historians have criticized Epstein over the band’s first recording agreement with EMI’s Parlophone label in June 1962. But the contract’s lopsided provisions favoring the record company were typical in a “baby-band” deal for new artists.

However, by the time of their wildly successful appearance in October 1963 on the British TV variety show Sunday Night at the London Palladium, the Beatles were no longer a baby band—having several No. 1 U.K. hits under their belt. This was the time when the media referred to “Beatlemania” and Epstein’s office was overwhelmed with licensing requests for the manufacture and sale of Beatles merchandise.

To begin with, neither Epstein nor David Jacobs, the London attorney Epstein retained, had much experience in negotiating merchandise agreements. They ended up granting exclusive worldwide licensing rights to a company owned by London nightclub owner Nicky Byrne and several young business partners—none of whom were experienced in the merchandise business. The arrangement was as lopsided as it was ill-advised, with Byrne’s company, Stramsact, receiving 90 percent of the proceeds from the sale of Beatles goods.

CARRY THAT WEIGHT

It was this Epstein/Stramsact deal that proved the first of many missteps for the Beatles on a lawsuit-strewn path that plagued them for the rest of the band’s legal life. Long before—and especially after—Epstein died of an accidental drug overdose in August 1967, the Beatles found themselves on the losing side of battles over nearly every aspect of their business.

For instance, Byrne and his partners founded a U.S. affiliate known as Seltaeb (Beatles spelled backward). In an early and ugly court battle that began in December 1964, Epstein and NEMS sued Seltaeb in New York state court, alleging underpayments of millions of dollars in Beatles merchandise royalties. However, the Byrne/Seltaeb defendants counterclaimed that Epstein was surreptitiously issuing unauthorized Beatles merchandise licenses that violated Stramsact/Seltaeb’s exclusive rights.

In May 1965, the New York Supreme Court dismissed the NEMS suit over Epstein’s refusal to sit for a deposition in the case. (Epstein had refused to travel to New York from England citing health problems, though he admitted in an affidavit he was “probably not as qualified to answer all the questions which may be put to me.”) The complaint was later reinstated by a New York appellate court; and shortly before Epstein died, the parties settled—with Epstein paying a hefty portion of NEMS’ legal fees out of his own pocket.

While researching the lawsuit, I found in the court files a copy of the royalty statement Seltaeb sent NEMS for U.S. merchandise sales of Beatles products from Feb. 1 to June 30, 1964. The statement claimed that Seltaeb owed Epstein and the Beatles just $79,624 in royalties for merchandise sold during the initial U.S. frenzy over Beatlemania. Taking withholding taxes and Epstein’s 25-percent-of-gross management commission into account, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr each would be owed a mere $10,275 based on the royalty monies Seltaeb reported. “We got screwed for millions,” McCartney later lamented about the Beatles’ merchandise deals.

TAX MAN

After Epstein’s death, the Fab Four had a go at running their own company, Apple Corps. The company, guided more by utopian intentions than prudent business principles, bled millions more in self-inflicted losses. “If I wanted to be a businessman, I would never have taken up drums,” Starr conceded in Rolling Stone in 1969.

To extricate themselves from their own bad decision-making, the group sought a new business adviser. Against McCartney’s prescient warnings, the rest of the Beatles settled on controversial, street-tough New York accountant and Rolling Stones manager Allen Klein. In doing so, the group rejected Lee Eastman and his son, John Eastman—the father and brother of McCartney’s future wife, Linda. Although Lee Eastman was a seasoned entertainment lawyer, the other Beatles feared McCartney’s increasingly outspoken influence over the group’s financial affairs, a resentment that fueled the eventual breakup of the group.

In late 1961, Brian Epstein saw the Beatles at the Cavern Club and began hatching a plan to manage them. As manager, Epstein changed the group’s image and got a deal with EMI’s Parlophone. But as Beatlemania struck, he missed the mark with merchandising. Photo Illustration by Stephen Webster; Getty Images/Corbis/AP Photo.

In fact, the beginning of the end came when McCartney sued his Beatles mates in the High Court of Justice in London in December 1970. The suit was aimed at ousting Klein, who would later be convicted of tax evasion in the United States. For a time, Klein continued to represent the other three Beatles until they became unhappy with him, too, and fired him in March 1973. This led to yet another volley of lawsuits—this time between Harrison, Lennon, Starr and their former manager. The complex litigations ended only when Apple Corps agreed to pay Klein $4.2 million to go away.

In some ways, he didn’t. Harrison, in particular, remained in Klein’s clutches. In August 1971, with Klein’s help, Harrison had put together what is considered the first major international charity concert by rock artists, to help starving refugees from civil-war-torn Bangladesh. But before the start of the shows in Madison Square Garden, Klein failed to file the proper nonprofit tax-exemption forms. As a result, the IRS moved to freeze for several years any distribution of the sizeable income from the Bangladesh charity events.

As if that didn’t cause Harrison enough damage, during Klein’s management litigation with his three Beatles clients, Klein launched an audacious scheme—discussed in the following excerpt from my book, Baby You’re a Rich Man—to seize ownership of Harrison’s most precious creative assets: the songs he wrote for his solo career and for the Beatles—music housed in his publishing company, Harrisongs.

HERE COMES THE SUMMONS

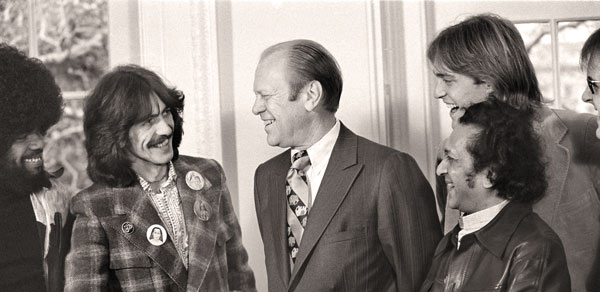

George Harrison stepped onstage at Madison Square Garden on the night of Dec. 19, 1974, for the start of his final three shows of the first nationwide U.S. solo tour by a former Beatle. A few days before, with tour members sitarist Ravi Shankar and keyboardist Billy Preston at his side, Harrison told journalists during a White House visit with President Gerald Ford that he enjoyed working with these musicians more than he had being a Beatle.

In fact, on the afternoon of Dec. 19, Harrison signed the historic agreement, at the Plaza Hotel in New York City, that settled Paul McCartney’s lawsuit to break up the Beatles & Co. band partnership. But Harrison had blown out his vocal cords during rehearsals for the solo tour, and his concerts were plagued by throat problems and poor press reviews.

As if that weren’t enough, when the Madison Square Garden show began, another thorny problem lurked in the arena: a process server hovered near the stage eager to hand Harrison a lawsuit summons from Allen Klein. Harrison’s former manager sought to seize Harrisongs Music Inc. Klein claimed he needed to do so to protect his company, ABKCO, which managed Harrison’s music-publishing catalog, from Internal Revenue Service efforts to obtain back taxes that Harrisongs owed the government.

If Klein’s lawsuit was successful, he would gain control of Harrison’s solo compositions from 1968 forward. These included the prized “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” from the Beatles’ White album, “Something” and “Here Comes the Sun” from Abbey Road, and the bulk of the songs from Harrison’s massively successful first solo album, All Things Must Pass.

Proceeds from Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh, the first-ever such charity event, were frozen for years because Klein failed to file the proper tax forms. Photo Illustration by Stephen Webster/Getty Images

Klein’s suit, in New York state court, arose amid the larger legal conflict that erupted after Harrison, John Lennon and Ringo Starr fired Klein as their manager in March 1973. Klein claimed the Harrisongs suit was “a simple one unrelated to the total history of relations” between ABKCO and Harrison and his companies. But Harrison’s Los Angeles lawyer, David Braun, said Klein had written him about the “enormity, complexity and sensitivity of” the Harrisongs matter. Braun believed Klein’s complaint against Harrisongs was in retaliation for a management suit that Harrison, Lennon and Starr filed against Klein in England.

Harrison had hoped that Lennon and Starr would perform with him at Madison Square Garden on the 19th, but they were no-shows—reportedly in part to avoid being confronted by Klein’s process servers. Paul and Linda McCartney attended Harrison’s last Garden show on the night of Dec. 20, but they sat in the audience wearing disguises.

Klein’s lawsuit sought control of Harrison’s solo compositions from 1968 on, including prized songs from the Beatles’ White album and Abbey Road, and most of the songs from his first solo venture, All Things Must Pass. Getty Images.

Harrison had been the target of summonses from Klein at other inconvenient times, too. When opposing counsel was deposing Harrison on June 26, 1973, in the infringement suit against him over his song “My Sweet Lord,” a lawyer at Rosenman Colin—

the Klein-affiliated firm that represented co-defendant Harrisongs Music in the “My Sweet Lord” case—suddenly “left the room,” Harrison said, “and came back with a deputy sheriff who gave me copies of what I am told were an order of attachment and summonses and other documents in cases being brought by [Klein’s] ABKCO against Apple Records and Apple Films Ltd.” Harrison claimed to be “very surprised” that Klein’s counsel “should take this action, especially as they had been involved in arranging the deposition.” Or as Harrison’s copyright litigator Joseph Santora put it: “In walk two of Klein’s thugs with legal papers they slapped on Harrison.”

Klein’s efforts to have Harrison served with the suit to take over Harrisongs could have been the basis for a Monty Python comedy movie. Harrison had traveled to New York City on Monday, Dec. 16, 1974, after playing a concert in Philadelphia. At about 10 p.m. on the 18th, John Loiacono, a private investigator who worked for Klein’s lawyers, went to Harrison’s New York City tour headquarters at the Plaza Hotel to serve Harrison with the summons. Loiacono knocked at Room 937, where Harrison concert promoter Barry Imhoff was staying. But when the imposing, 300-pound Imhoff opened the door, he told Loiacono that Harrison wasn’t around and ordered the private investigator to leave.

Loiacono went to the hotel lobby to wait. There the Plaza’s night manager told Loiacono that he couldn’t serve a lawsuit summons at the hotel unless accompanied by police. As Loiacono later told it to ABKCO litigator Peter Nadel, at that moment “four policemen arrived in response to an earlier call from some other party about a disturbance.” Loiacono convinced the officers to return with him to Imhoff ‘s room. Imhoff allowed one of the officers to search the room, but there was still no sign of Harrison.

The next day, Loiacono went to Madison Square Garden, where preparations for Harrison’s show were underway. The persistent private investigator got backstage twice before being ejected each time by Garden security guards. So he obtained a ticket for that night’s concert and walked down to the stage area while opening act Shankar and his group were playing. Loiacono’s prospects appeared to be improving: his prey Harrison sat on the side of the stage talking with current manager Denis O’Brien. Loiacono jumped into the moat that surrounded the stage platform, but he was once again repelled by a Garden security guard.

Loiacono went back to the Plaza at around 10 p.m. to wait for Harrison, this time reinforced by three additional private investigators. Two of them took up watch outside the hotel, while the third stood near the elevators at the Plaza’s 58th Street entrance. Loiacono positioned himself at the main elevator bank near the Plaza’s 59th Street entrance.

Billy Preston, Harrison, President Gerald Ford, son Jack Ford and Ravi Shankar at the White House. Photo Illustration by Stephen Webster/Getty Images.

Within an hour, Harrison’s entourage arrived from Madison Square Garden. Imhoff immediately spotted Loiacono. To distract the process server, Imhoff began following him around the hotel lobby, asking questions while a cameraman and lighting assistant who happened to be with the Harrison group recorded the scene. This allowed Harrison the opportunity to bolt from his car and scurry through the hotel lobby into the safety of the hotel’s kitchen elevator.

But Loiacono’s process-serving adventure was far from over. Imhoff pointed him out to a Harrison bodyguard who Loiacono said was “about 25 years old, 6 feet 4 inches tall, 220 pounds, had blond hair and a blond beard, was extremely muscular and looked like a weightlifter.” “Get that guy in the suede jacket,” Imhoff commanded.

The escalating altercation quickly spilled out into the street as Imhoff and the bodyguard chased Loiacono to a car in which the other three private investigators were now waiting. When a New York City police car pulled up at the scene, “Imhoff and the bodyguard refused to identify themselves,” Loiacono claimed. “Imhoff denied knowing Harrison, even though he was wearing the same black T-shirt with the emblem worn by the Harrison party.”

Loiacono didn’t leave. With the two New York police officers at his side, he returned to Imhoff’s Plaza hotel room, where a “large party was spilling out into the corridor.” But Imhoff barred the warrantless officers from entering the hotel suite. When Loiacono insisted he still “would serve Harrison onstage if necessary,” Imhoff and other entourage members broke into laughter.

On Friday, Dec. 20, another of Klein’s investigators, William Ward, checked into a room on the Plaza’s ninth floor, then went to Madison Square Garden for Harrison’s 4 p.m. concert. Like Loiacono, Ward gained access near the stage on which Harrison stood, again watching Shankar’s Indian musicians perform. Ward walked up to Harrison’s thin, bearded and bespectacled manager O’Brien, tapped him on the shoulder with Klein’s legal papers and said, “I have summonses here for George Harrison; if I can’t serve him I must serve you. May I serve him?”

“No, no, no,” O’Brien said, backing away.

Ward dropped the papers at O’Brien’s feet and announced, “You are served.”

This article is excerpted from Baby You’re a Rich Man: Suing the Beatles for Fun and Profit by Stan Soocher; published by ForeEdge, an imprint of University Press of New England. Photograph Courtesy of Stan Soocher.

Ward did try to serve Harrison personally later that night, at the Hippopotamus Club on East 62nd Street in Manhattan, where Harrison’s group was celebrating the end of the national tour. But as Ward later described the scene to Nadel: “Eight men formed a circle around one of the car doors from which Harrison emerged. The whole group then made a fast dash into the club.” Ward decided to leave because “it would be impossible to approach Harrison upon his exit from the club in light of the human wall of bodyguards surrounding him.”

After all the cloak-and-dagger intrigue, Klein’s process servers had to rely on more traditional means of getting the summons to Harrison, by leaving copies at the offices of Harrison’s New York lawyers and mailing another to Harrison’s Friar Park home in England. But as it turned out, the case wouldn’t last long.

Harrison had formed Harrisongs Music Inc. in the United States in March 1969. After the IRS audited Harrisongs’ financial books in 1974, it sent a demand notice to the publishing company seeking $18,000 in back taxes. New York City issued a warrant against Harrisongs seeking at least $4,000 in corporate taxes and interest.

Klein claimed that, since the IRS audits began, Harrison “refused to deny or admit” he owned Harrisongs’ corporate stock. ABKCO sent letters to Braun seeking clarification, but Klein said, “No reply has been forthcoming.” Even though ABKCO’s lawsuit predicted “Internal Revenue Service and other tax agencies will undoubtedly continue to make demands on” Harrisongs catalog manager ABKCO, Klein was certainly willing to accept the responsibility in exchange for ownership of Harrisongs Music Inc. After all, he would get worldwide rights to Harrison’s musical compositions, outside the United Kingdom, for incurring relatively modest tax liabilities.

ABKCO had kept Harrisongs’ financial books at its offices since Harrisongs was founded. But Braun charged that, after Harrison terminated Klein as his manager in March 1973, “ABKCO refused to turn over the HMI books and records and insisted upon continuing to manage the affairs of HMI.” As proof, Braun noted that in June 1973 Klein wrote the Harry Fox Agency, the industry clearinghouse for publishers that collected song income from record sales, “to send all payments, checks, licenses—indeed, ‘anything having to do with Harrisongs Music, Inc.’—to HMI, in care of ABKCO.”

Klein argued, however, it was Harrison who “had the sole power to sign checks on HMI’s bank account.” By June 1975, Harrison admitted he owned Harrisongs Music Inc.’s stock and ABKCO agreed to hand over the Harrisongs legal and financial records it held. This allowed Harrison to clear up his dispute with the taxing authorities. He said he had been disclaiming ownership of the publishing company because his English lawyers “told me I did not own it, although they seemed to have trouble making up their minds.”

On June 17, the state court formally closed the ABKCO/Harrisongs case file. But Klein would soon hatch an alternate plot for trying to turn Harrison’s music into a future revenue source for ABKCO. The original idea came to him in the middle of the copyright-infringement suit that was filed against Harrison over his worldwide hit “My Sweet Lord,” when Klein was still his manager. After the split from Harrison, Klein would woo the musician’s foes in the infringement action.

Photo Illustration by Stephen Webster/Getty Images

‘MY SWEET LORD’ V. ‘HE’S SO FINE’

Allen Klein worked unsuccessfully with George Harrison to fend off the copyright infringement suit over “My Sweet Lord” that was filed by Bright Tunes Music, the publishers of the Chiffons’ 1963 hit “He’s So Fine.” In September 1976, New York federal Judge Richard Owen ruled that Harrison at least subconsciously infringed on “He’s So Fine,” which was a chart hit in England at the same time in 1963 as the Beatles’ No. 1 recording “From Me to You.”

But Klein believed he could personally benefit from the “My Sweet Lord” case. For $587,000 he purchased the right from Bright Tunes Music, which needed money to pay its trial lawyers, to collect the $1.6 million in infringement damages assessed against Harrison. An annoyed Judge Owen limited Klein to recovering $587,000. Unfortunately for Harrison, though, there was a Harrison/Klein dispute over accounting issues involving “He’s So Fine” that Harrison and Klein wouldn’t resolve until 1998.

By then an unlucky Harrison was embroiled in yet another legal mess with a personal manager. In this one, Harrison was trying to collect an $11 million judgment that the Los Angeles County Superior Court awarded him in a suit he filed against Denis O’Brien, Harrison’s manager from 1973 to 1993. Harrison had alleged O’Brien mishandled the artist’s finances by, for example, “enrich[ing] himself and liv[ing] on a lavish scale at Harrison’s expense, buying yachts and villas in various parts of the world, while Harrison suffered enormous losses and liabilities as a result of O’Brien’s improper and inept management and deceitful conduct.”

The creative impact of the case was so intense on Harrison that he told Billboard magazine, “I’ve hardly ever picked up the guitar” during the litigation.

Harrison never secured the $11 million judgment from O’Brien. Instead, in 2000 O’Brien filed for bankruptcy in a Missouri federal court. Harrison challenged the bankruptcy, but after he declined to travel to St. Louis from England for a July 2001 deposition, on the ground that aggressive cancer attacking his body made the trip impossible, the bankruptcy judge ruled in favor of O’Brien.

Unfortunately, Harrison died from the cancer just four months later.

• Excerpted from Baby You’re a Rich Man: Suing the Beatles for Fun and Profit by Stan Soocher; published by ForeEdge, an imprint of University Press of New England.

This article originally appeared in the May 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Did Litigation Kill the Beatles? Tracing the roots of the Beatles’ legal woes.”

Stan Soocher is an entertainment attorney and the longtime editor-in-chief of Entertainment Law & Finance. He is also an associate professor of music and entertainment industry studies at the University of Colorado in Denver. Baby You're a Rich Man is his most recent book.