Features

Clemency Project 2014 is out to help prisoners doing excessive time due to inflexible sentencing

Photo illustration by Wayne Slezak

As he describes it, Ledford was "a mixed-up, messed-up dude" addicted to methamphetamine. Ledford's addiction had already sent him to state prison twice, left his children to be raised by grandparents, and cost him his job as a mechanic in his family auto repair business.

"I got arrested four times in 11 months. I was just on a drug-induced ride—me and the girl I ended up marrying," he says. "I got out of prison March 28, 2002, and I was back locked up on March 11, 2003."

Ledford's state convictions were all for drug possession or related offenses, like theft and possession of a firearm by a felon. But in 2003, Ledford says, he was also selling "enough drugs to stay high." When his wife was pulled over by a Lake Alfred, Florida, police officer, there was more than a pound of meth in the trunk. Ledford immediately claimed it to save his wife from facing more charges.

Unfortunately for Ledford, that got him a federal charge—possession of 500 grams or more of methamphetamine with intent to distribute. His public defender at the time, Adam Allen of the Middle District of Florida, says Ledford would normally have been looking at a little under 22 years in prison.

But when a defendant has two or more felony drug convictions—Ledford had four—prosecutors have the option to enhance the sentence, under 21 U.S.C. § 851, to mandatory life in prison. And at the time, the U.S. attorney's office sought Section 851 enhancements whenever possible, even in low-level, nonviolent cases like Ledford's.

Ledford knew he would be sentenced to life, but he nevertheless pleaded guilty.

"I was hoping that by pleading out and claiming the drugs, they would see that I was trying to do the right thing and would show some mercy on me," Ledford says.

"He's never, ever refuted his guilt," says Allen. "One of the ways under the law to get out from under the life enhancement is to cooperate, and Mr. Ledford did anything and everything he could to try to reach that level."

But it never worked out. According to the sentencing transcript, Judge Richard Lazzara said he took no pleasure in handing down the life sentence, but "there's no question I have to give him life." Twelve years later, after a direct appeal and a habeas petition failed, Ledford, now 45, is still serving a life sentence.

NEW HOPE

Normally, that would be the end of the story. But last year, the Department of Justice announced an extraordinary project that could provide relief to Ledford—and perhaps thousands of others in similar positions. In January 2014, the department announced a plan to shorten thousands of long sentences handed down for nonviolent drug crimes, using President Barack Obama's clemency power.It's a radical departure from the way modern presidents have used clemency. Rather than correcting injustices here and there, the project seeks to systematically reduce sentences handed down during an era of inflexible sentencing.

Equally extraordinary was the Justice Department's call for help from the private bar. Because an influx of pro se petitions could overwhelm Justice's small Office of the Pardon Attorney, the DOJ asked private attorneys to volunteer their help.

Enter Clemency Project 2014. About 1,500 volunteer attorneys have come forward to help eligible prisoners submit the best possible clemency petitions. This small volunteer army is being led by five groups of criminal justice stakeholders: the American Bar Association's Criminal Justice Section, the American Civil Liberties Union, Families Against Mandatory Minimums, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, and a group of federal defenders—the heads of the 84 offices of federal public or community defenders.

"It is unprecedented, it is important—and the chance of a lifetime for a defense attorney to be able to walk someone out the prison doors this way," says Donna Lee Elm, the federal defender for the Middle District of Florida and part of the CP14 management.

Clemency cases move slowly; FAMM says an answer typically takes from two to seven years. But CP14 doesn't have that much time. Because the project relies on Obama's power to grant clemency—and there's no guarantee his successor will embrace the project—all decisions have to be made before January 2017.

That stress was increased last July when one fertile source of volunteers was cut off. A memo from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts forbade federal public defenders from actively representing CP14 clients, though they may still do administrative work.

And although there is increasing bipartisan support for sentencing reform, CP14 has drawn criticism from both the right and the left. Among other complaints, critics say the federal government shouldn't allow nongovernmental groups to be so heavily involved in making policy.

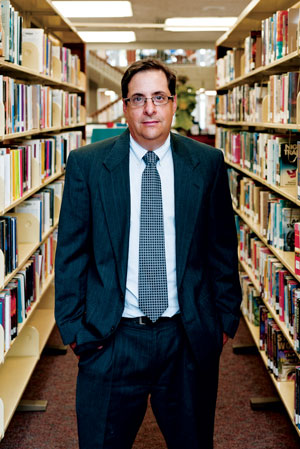

Jim Felman, ABA Criminal Justice Section co-chair. Photo by Alicia Katherine Johnson.

Nonetheless, CP14 leader Jim Felman—Ledford's current attorney and co-chair of the Criminal Justice Section—says this is the chance the criminal defense bar has waited decades for.

"There are thousands of people languishing in prisons serving sentences that were handed out over draconian sentencing laws," says CP14 project manager Cynthia Roseberry. "This is a historic opportunity to reverse that."

CP14 relies on the constitutional power to grant clemency—pardons, sentence commutations and other actions that ease the consequences of a conviction.

Though Obama's past statements have suggested he's concerned about unduly harsh drug sentences, he's made little use of his clemency powers. That's the case in general for presidents serving from 1980 onward.

But even compared with his modern predecessors, the president has hardly used his clemency power. A December report from the investigative journalism group ProPublica notes that even counting pardons issued that month, Obama had issued fewer pardons than any other modern president at a comparable point in their presidencies. ProPublica did find, however, that Obama had issued more commutations at that time than any of his two-term modern predecessors—but this was up sharply from 2012, when he had issued just one. (He issued 22 more this March.)

One reason might be that Obama, like President George W. Bush before him, relies on recommendations from the Office of the Pardon Attorney—and the OPA has recommended very few cases for clemency since 2001, according to a 2011 ProPublica report. In an interview with the Huffington Post this year, Obama said that before 2014, the office had been sending him cases that, while "legitimate … didn't address the broader issues we face, particularly around nonviolent drug offenses."

However, politics may have kept both presidents from making a change. ProPublica said Bush started relying on the OPA in direct response to President Bill Clinton's out-the-door pardon of Marc Rich, a commodities trader who fled to Switzerland pending his 1983 indictment on racketeering charges. Critics claimed that Rich bought his pardon after his ex-wife contributed to Hillary Clinton's Senate campaign and to the Clinton library.

Kenneth Lee, a former associate White House counsel under Bush, told ProPublica: "You can't overestimate the shadow of that case. There is very little political benefit in granting pardons or commutations, but the blowback can be huge."

And to make the optics worse, the 2011 ProPublica analysis showed that those who did get clemency were overwhelmingly white. Having friends in government also helped; applicants often skirted the OPA and went directly to the White House.

"It's not that, well, everybody's getting clemency and some people are getting it more than others," says Douglas Berman, a sentencing law expert and professor at Ohio State University's Michael E. Moritz College of Law. "It's that almost nobody's getting clemency, and the occasional person who does is a white, rich, politically connected male."

Berman, who runs the Sentencing Law and Policy blog, says this reluctance to grant clemency arose at a time when the need was greater than ever. He points not only to long "war on drugs" sentences—particularly those for crack—but also to the 1984 elimination of parole for the vast majority of federal prisoners, which removed a tool to recognize good behavior or ease a long sentence.

"The federal prison population and the scope of the justice system is historically large," Berman says. "What used to be a lake of federal offenders who might want some clemency relief is now a Pacific Ocean."

A DOGGED ATTORNEY

Ledford is unusual in that he had help with the clemency application from the start. When CP14 was announced, Allen started in on Ledford's paperwork right away."All of my cases stick with me, but this one even more so in light of the sentence that he ended up receiving," Allen says. "I was very troubled by the sentence he got and asked one of our brighter appellate lawyers to please handle his appeal, because I just don't think I could have stomached not prevailing on appeal."

Adam Allen, assistant federal public defender. Photo by Alicia Katherine Johnson.

"I think a lot of Mr. Allen. I'm guessing that not many people can say that of their public defender," Ledford says. "Mr. Allen never gave up on me, even when I was over my court proceedings."

For his part, Allen was impressed with Ledford's efforts in prison to turn his life around. Ledford kicked meth, got his GED, took vocational classes and says he's worked at important jobs for almost all his time inside. Perhaps most impressively, Ledford's behavior has been good enough to allow him to be moved from a maximum-security facility to a medium-security facility—which is rare for lifers.

"I suspect a lot of people would be like 'I got life in prison—what freaking difference does it make?' But he's really taken advantage of every possible opportunity in prison to improve himself," Allen says.

That will help Ledford's clemency petition. Under the criteria laid out by the Justice Department, eligible inmates must have a record of good conduct in prison. They must also have served at least 10 years of their sentences, have no significant criminal history nor a history of violence before or during their sentences.

Perhaps most important, they must be serving a long sentence that, by law or policy, would be shorter today. In Ledford's case, the change was in Justice Department policy on Section 851 enhancements. A 2013 policy memo told prosecutors that the enhancement should be reserved for people "involved in conduct that makes the case appropriate for severe sanctions," such as violence or organized crime.

Another major group likely to benefit is crack cocaine offenders who were sentenced before the 2010 Fair Sentencing Act reduced crack penalties. Berman says there may be 2,000 to 10,000 such prisoners.

Cynthia Roseberry, CP14 project manager. Photo by David Fonda.

A tougher call will be whether the U.S. Supreme Court's 2005 decision in United States v. Booker, by itself, is enough of a change in the law to make a prisoner eligible for CP14. Booker made the sentencing guidelines advisory, ending a mandatory sentencing scheme that had been criticized for tying judges' hands.

During a talk at the ABA's 2015 midyear meeting, Felman said that CP14 will likely submit applications relying on Booker anyway and hope for the best.

SCOPE OF THE REVIEW

Submissions come after a lengthy review process. Normally, clemency seekers submit their petitions directly to the OPA (either pro se or by using one of the few lawyers who specialize in clemency). An OPA lawyer then scrutinizes the petition closely, typically calling the prosecutor's office and judge involved in the original case for an opinion. Once that work is done, the deputy attorney general (currently Sally Quillian Yates) examines it and sends it to the White House with the office's recommendations.Though petitioners are still free to take that direct route, those going through CP14 get additional review. For those without Ledford's close relationship to a former attorney, the process started with a survey sent out last year by the Bureau of Prisons, asking whether the prisoner meets the DOJ's clemency criteria. As of early June, CP14 had received more than 30,000 of them. Any volunteer attorney who has completed CP14's training—a six-hour online course—may take up one of those surveys. Volunteers dig through old documents to investigate whether the prisoner really meets the criteria, then create an executive summary. That goes to a screening committee, whose job is to thoroughly double-check whether the case meets the DOJ's criteria.

If the case gets through that round, it goes to a CP14 steering committee, which is responsible for ensuring that each of the project's five partner organizations is comfortable signing off on the case. That's a lot of layers of approval, but Felman says organizers felt each was necessary because they all have different functions.

If the case is approved, the volunteer attorney drafts the actual petition. The petition goes to the Office of the Pardon Attorney with a cover letter from CP14, saying the project organizers believe this prisoner meets the criteria. From there, it's out of CP14's hands.

"I'm not saying that that [letter] gives that petition any special weight over there," Felman explained at the midyear meeting. "Our hope is it gives them a little more confidence. But there's no question that they will put it through their regular, routine process."

If the OPA approves a case, it goes to the Office of the White House Counsel. From there, Felman says, CP14 doesn't know what happens. Several emails to the White House press office were unreturned. Clemency Project 2014 petitions began going to the OPA at the end of 2014. In March, the president issued the first four commutations with project involvement, as part of a group of 22 commutations. Though it's hard for CP14 to predict what the president might do, Felman says he's been told the White House would like to start approving cases on a quarterly or even rolling basis. He notes that the March commutations were issued at the end of the year's first quarter and says he would not be surprised to see more issued at the end of the second quarter. This would be another departure from modern presidents' standard practice of granting clemency at Christmas or the end of their terms.

Even when petitions are approved, it's not clear whether clemency recipients will be able to go home right away. No government representative has commented on the issue, but Felman says CP14 has assumed the president will shorten sentences to what they would have been if handed out today. But the March commutations didn't follow that formula; all but one recipient were slated for release at the same time, in July.

If CP14 is right, the majority of recipients will still have time left on their sentences. That includes Ledford. Felman says the lower end of the sentencing guidelines for Ledford's crime, without the Section 851 enhancement, would get him about 22 years.

"He'll have to do eight or nine [more] years in prison," Felman said at the conference. "So they're not letting you walk out the door. But he is going to have hope now."

Originally, Allen thought he would represent Ledford throughout this process. In fact, he says, his office assumed it would represent all of its former clients. But the July 2014 memo issued by the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts ended those plans. Its general counsel, Robert Loesche, said federal public defenders may not represent CP14 clients because noncapital defendants have no legal right to counsel for clemency purposes.

The memo instantly barred 3,300 federal public defenders and community defenders from actively representing clients through CP14.

"It really was a disappointment, because we were counting on the defenders to handle a huge chunk of these cases," Felman said at the midyear meeting. "A lot of [petitioners] were their clients."

That's how Felman ended up taking Ledford's case. After learning that he couldn't handle it himself, Allen approached Felman, a friend and fellow defense lawyer in Tampa.

MORE VOLUNTEER LAWYERS NEEDED

Despite the ban on direct representation, federal public defenders are still contributing to CP14. The memo expressly says defenders may "screen ... client files to identify individuals who may satisfy the criteria." Many have been finding the case files of former clients who might qualify, organizing them and writing a memo explaining the case for any CP14 volunteer who takes it up. Elm, the Tampa federal defender, says this is "inherent in our obligation in turning over a file to another lawyer."And defenders are also acting as leaders. Felman says seasoned public defenders are running a hotline for volunteers and serving on committees. Elm and Kathryn Nester, federal defender for the District of Utah, represent their fellow defenders as stakeholders on CP14's 10-member steering committee. The CP14 group of federal defenders is not a formal organization, so Elm and Nester have no role as spokeswomen.

But the loss of the defenders exacerbated another problem: insufficient volunteers. The project has quite a lot already—about 1,500 as of early June—and is recruiting from large law firms and law school clinics. But with roughly 30,000 prisoner surveys to review—and the end of President Obama's term looming—CP14 needs more.

Another problem, which is endemic to old cases, involves getting the paperwork. Because the Justice Department requires petitioners to have served at least 10 years in prison, the cases are at least that old. That makes it tough to establish a prisoner's eligibility, especially if no former attorney can forward the case file. Many of the cases require an in-person trip to a courthouse because older documents are not on PACER.

Even tougher to get are the presentence investigative reports, or PSRs, which are usually sealed. Felman said at the midyear meeting that a handful of judges have denied requests to unseal them; and in one case, a prosecutor opposed it.

"We do get word that there's some institutional resistance within the department," he said at his talk. "I'm sure that there are some prosecutors out there thinking 'I worked my butt off to get that guy life.' "

That's not so in Ledford's case. His original prosecutor, A. Lee Bentley III, is now the U.S. attorney for the Middle District of Florida. Though Bentley declined to be interviewed, Felman says that he is sympathetic to the project, and he didn't want to file the Section 851 enhancement against Ledford in the first place.

But Felman cautions that CP14 is not about finding sympathetic figures, or rewarding people with clean pasts. "[Federal authorities] know these are not good people necessarily," he told the midyear meeting panel. "This is about justice and correcting excesses in sentencing."

Moreover, critics of CP14 aren't just law-and-order advocates. In fact, the project has been criticized by some of the most ardent supporters of clemency.

On the political right, one critic has been Iowa Republican Sen. Charles Grassley. Though Republicans have increasingly embraced sentencing reform—the Smarter Sentencing Act being considered by Congress this year has bipartisan backing—Grassley has not. In January, he sent Justice a letter raising concerns that the department had "delegated ... core attributes of presidential power to private parties beholden to no one." The Justice Department had not publicly responded as of May, and did not respond to requests for information.

Another conservative organization, the watchdog group Judicial Watch, has sued the DOJ under the Freedom of Information Act in an effort to get records of its communications with CP14 partner organizations. Judicial Watch president Tom Fitton says this is a rule of law issue. "There's this effort to abuse the clemency power of the president, to bypass Congress' sentencing laws," he claims. "The whole project by itself is an affront to the idea that the clemency power of the president is exercised on a case-by-case basis."

Fitton also echoes Grassley's concern about non-governmental organizations "operating as, in effect, government agencies."

TOO MANY LAYERS OF BUREAUCRACY?

Even some who are sympathetic to clemency see some merit in those concerns. One such person is Berman, whose main criticism of clemency is that it's so rarely used. Normally, he says, public policy groups with agendas should not be called upon to rewrite federal policy, such as undoing sentences issued under previous rules.Felman says this is driven by a misconception that CP14 organizers have any authority or special access to executive powers. Felman says moving in these circles has been exciting—he took a selfie at the White House—but the Justice Department wasn't much interested in CP14 leadership's opinions about the clemency criteria. And in the end, he says, the Justice Department and the White House will decide who gets clemency.

"What we're doing is responding to their request for help from the bar," he says. "Yeah, it might save them some manpower, but it isn't a delegation of any kind of government authority."

But Berman is also concerned that the Obama administration's use of outside help could mean that it's not very committed to the project.

"If this really was a priority, ... there's plenty of people that the federal government can operationalize," he says.

And he has problems with the slow pace of the project. As a sometime advocate for clients seeking clemency, he's very aware that the OPA and the White House require a lot of time to examine requests. He just doesn't think it's necessary. Rather, he says, it's an excessively cautious approach that prioritizes politics—that is, getting "buy-in from everyone who could complain about a bad grant."

Law professors Mark Osler of the University of St. Thomas (who runs a commutation clinic) and Rachel Barkow of New York University might agree. They argued in a November Washington Post op-ed that the clemency process has far too many layers of bureaucracy and creates a conflict of interest because the Justice Department reviews convictions won by its own prosecutors. They called for a stand-alone, bipartisan agency like those used for clemency in many states.

Other critics from the left contend that the DOJ criteria leave too many prisoners out—particularly those who meet all criteria except the 10-year requirement. Felman says CP14 organizers pushed back a little on this issue, but to no avail. Both Felman and Berman encourage people who don't meet all the criteria to submit clemency applications directly to the OPA anyway, as CP14 is not the exclusive path to clemency.

And Berman worries that CP14 is a missed opportunity to make permanent changes to the manner in which modern presidents approach clemency.

"Even if we get a lot from the president, unless it involves a systematic sea change in the way clemency is approached, it isn't going to have the kind of lasting transformative effect that a heck of a lot of other work can," he says.

But even if longer-term reform doesn't happen, Berman acknowledges that CP14 could still make a big difference in recipients' lives. One of those lives could be Ledford's.

"When you are given a sentence of life in prison, you really begin to think about what you have lost and even more of what you will lose in the time to come," Ledford says.

Ledford knows that he might not get out of prison right away if he wins a commutation. Nonetheless, he says his family is really excited about the possibility. His father has been talking about reopening the family auto repair business together, and his brother has spoken to his boss about a potential job for Ledford. Ledford's nephews, 6 and 8, are clamoring to share their rooms with their uncle. Ledford himself is eager to take over care of his youngest son, a teenager with Asperger's syndrome, from his father.

And even knowing that he might never get to leave prison, he says his life is better than it's ever been.

"I have a wonderful family that loves me, an awesome support group in here that helps me learn and grow, and some great people that believe in me enough to help," he says. "I'm clean, I'm sober, I'm educated—the whole nine yards."

"You wouldn't think that about me being in prison, but this is the best I've ever been in myself in my life."

This article originally appeared in the July 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “A Thousand Pardons: Clemency Project 2014 is out to help prisoners doing excessive time from the days of inflexible sentencing.”

Sidebar

istockphoto

Drug Crimes Are Prominent in Clemency Bids

In April of 2014, when the Justice Department announced the criteria for its clemency initiative—the basis for Clemency Project 2014—it didn't choose specific crimes of conviction. Rather, the criteria said clemency could be granted to "nonviolent, low-level offenders without significant ties to large-scale criminal organizations," who have served at least 10 years of a sentence that, if imposed today, would be substantially lower.Those criteria encompass a lot of crimes of conviction—at least potentially. The federal defenders have many memos out about situations in which an offender might receive a shorter sentence today. These include memos on 21 U.S.C. § 851 enhancements; the Armed Career Criminal Act; the 2014 amendments to the drug quantity tables ("Drugs Minus Two"); and several recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions that affect sentencing.

But the focus, from the media and a lot of those interested in clemency, has been on drug crimes. Drug crimes meet the criteria: They typically involve long sentences but do not have to include violence, and America is increasingly willing to shorten drug sentences. One high-profile example is the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which reduced (but didn't eliminate) the sentencing disparity between crack cocaine crimes and powder cocaine crimes.

Ohio State University law professor Douglas Berman, who studies sentencing, speculates that a lot of clemency recipients could be crack cocaine offenders sentenced in the late 1990s and early 2000s. He says maybe 2,000 to 10,000 prisoners have not gotten the benefit of the Fair Sentencing Act and other reforms to crack cocaine sentences.

"They're the most obvious examples of folks who both have been subject to the old law and haven't gotten the benefit of any new laws—and who are serving long sentences that the president potentially could do something" about, Berman says.