Civil rights lawyers from the 1960s have lessons for today's social activists

Paul Harris. Photo courtesy of Paul Harris

IN HIS BLOOD

Unlike Bingham, being a radical was in Harris’ blood. His uncle, Fred Fine, was a leading member of the Communist Party USA, while his father volunteered to fight in the Spanish Civil War against Francisco Franco and the Nationalist forces. Growing up during the McCarthy era, Harris was too young to understand what was going on, but he knew his family was suffering.

“My father was blacklisted out of the labor movement,” Harris says. “My mom lost six jobs in seven weeks. My uncle was indicted under the Smith Act and went underground for four years. The FBI would show wanted posters of my uncle and [my mother would] get fired. It was horrible for my parents and grandparents.”

Harris was never a Communist himself (though he says he joined some Marxist groups in college), but he was clearly influenced by party tenets. Nowhere was this more apparent than when he set up the San Francisco Community Law Collective in the Mission District immediately after graduating from Berkeley Law in 1969.

Describing it as “communist—with a lowercase c,” Harris says the law collective was based on the idea that communities could have legal representatives similar to in-house counsel to serve them whenever legal issues came up. The radical twist was its compensation structure: All employees were paid equally, regardless of whether they held a JD.

“Our model was for a completely multiracial law office that would work hand in hand with community groups,” says Harris. “We weren’t really looking to do big political cases. We just wanted to empower people so that they could bring about long-term changes.”

But the big political cases soon found their way to Harris’ desk. Leonard McNeil, a collegiate All-American football player at California State University at Fresno, was drafted by the Philadelphia Eagles in 1968. His number also came up in a different, far more serious draft—the military one.

“He fled to Canada after getting a draft notice,” says Harris, who notes that McNeil had been active in civil rights demonstrations in college and claimed that the Eagles refused to sign him because they believed he was a Black Panther. “He came to me because we were known as experts in draft law—and because we were leftists.” Harris got the charges dropped, and McNeil went on to an active political career, including 12 years on the San Pablo city council and one term as mayor.

Harris had worked with the Black Panther Party and says he had respect for its members after seeing the positive things they had done in the community, including taking seniors to the bank to help them cash Social Security checks, setting up free breakfasts and developing programs to help people with sickle cell anemia.

Contact with the Panthers brought Harris into a case involving their minister of defense, Huey Newton. Newton, who had attended law school in San Francisco, was facing murder and assault charges and had decided to abscond to Cuba.

“I was asked to go to Cuba and meet with Huey and get him to come back and face the charges,” Harris says. “I told him that he’d probably win the murder case but lose the assault. Huey told me: ‘Paul, I love Cuba, but I’d rather spend the rest of my life in prison in my home country than live in exile.’”

Harris defended Newton on the assault charge and, contrary to his initial prognosis, got an acquittal. He did not take on the murder case, however. Instead, it was a fellow Berkeley Law alumnus who would handle it.

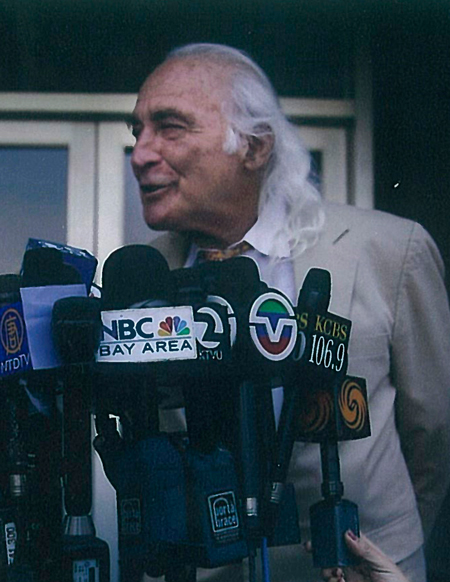

J. Tony Serra at a press conference. Photo courtesy of J. Tony Serra.

AGAINST THE GRAIN

That lawyer, J. Tony Serra, likes to call himself an “anti-lawyer lawyer.” Serra went to Stanford University for undergrad before graduating from Berkeley Law in 1961. Serra had dreams of being a big-time mob lawyer, but he was soon swayed by something else that was going on at the time: the Summer of Love.

Located about an hour from Boalt Hall, the Haight-Ashbury area became ground zero for the free love movement, and Serra was immediately hooked. His attraction to what was going on in Haight-Ashbury went beyond hippie culture. “Out of it all came a fusing of Eastern ideology and Eastern religion with Western ideology,” Serra says. “We were all working together.”

Perhaps that’s why he sounds as if he’d love to go back in time. Calling it the “golden age of law,” Serra waxes nostalgic for those days.

“We always romanticize our youth,” says Serra. “That’s when we were strongest, most mentally able and most innocent. I was a radical lawyer in an era where I could win consis-tently, and the Constitution was respected and fulfilled to a degree that certainly was much more prominent than presently.”

Nevertheless, he’s tried hard to uphold the ideals that he stood for in the ’60s, even as the decades have progressed. While on an LSD trip, he took a vow of poverty, and he still lives a frugal lifestyle. He tries to keep his fees as low as possible so that he can help as many poor clients as possible.

He says he typically charges $25,000 for a death penalty case, knowing he could get nearly 10 times that working as a court-appointed attorney.

“You must strip yourself of impure motives if you want to be successful in any idealistic venture,” Serra says. “If I’m thinking about money, then I can’t defend my clients effectively.” That extends to giving money to Uncle Sam: Serra is a well-known tax resister and even spent 10 months in federal prison in 2005 for evasion.

He has another reason for living a Spartan lifestyle. Decrying the materialism he sees from many in the profession, Serra believes it’s hypocritical for lawyers to say they believe in a cause only to chase money. “They pretend they believe in a correlation between income inequality and racism, and then they go to expensive restaurants and go yachting on weekends,” says Serra. “They want it both ways.”

When Serra defended Newton on charges that he had shot a prostitute to death in 1974, it was Serra’s first high-profile case. He remembers how Black Panthers stood in the courtroom, and in the halls outside of it, cheering him on as he made his arguments in open court, calling out as if they were in church. He also formed an indelible bond with his clients, one that continued to influence him long after Newton was killed in 1989.

“Huey was one of the most magnificent people I’ve ever met,” says Serra. “He taught me so much. For a short but intense period, we were like brothers.”

Serra, who went on to represent other radical defendants, including members of both the Black Panthers and the White Panthers, as well as the Symbionese Liberation Army, says he’s learned from all his clients.

“They were all brilliant people, very analytical and self-sacrificing,” Serra says. “I got close to all of them—not just because I represented them in court and won, but because we became friends. Their ideologies framed my ideology.”

Like other radical lawyers, Serra has found himself in the cross-hairs of law enforcement. In addition to his tax issues, Serra was accused of releasing the contact information of two police witnesses to the public in a criminal trial. He called on a fellow California radical to get the charges dismissed.

Correction

Print and initial online versions of "Resistance Redux,” August, should have stated that six inmates at San Quentin State Prison allegedly tried to escape. It also should have stated that Paul Harris was Stephen Bingham’s defense attorney at his preliminary hearing but was no longer representing him at his acquittal.The Journal regrets the errors.

Clarification

“Resistance Redux,” August, should have stated that J. Tony Serra typically charges $25,000 for a death penalty case, knowing he could get nearly 10 times that working as a court-appointed attorney.

This article appeared in the August 2017 issue of the ABA Journal with the headline "Resistance Redux: Civil rights lawyers from the 1960s have lessons for today's social activists."