Resistance Redux: Civil rights lawyers from the 1960s have lessons for today's social activists

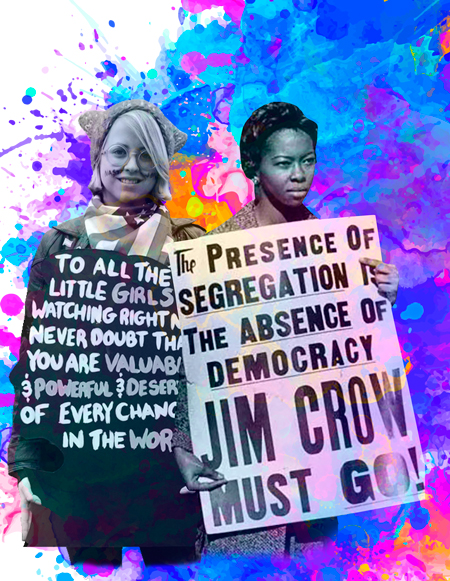

Photo illustration by Monica Burciaga

When Stephen Bingham and Timothy Jenkins remember traveling to Mississippi in 1964 to take part in the Freedom Summer, with the stated goal of registering African-Americans to vote, they recall being exhilarated. It was an exciting time for the civil rights movement and the two—along with thousands of other volunteers from the NAACP, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Congress of Racial Equality, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the rest of the rich alphabet soup that is part of historical lore—felt energized and inspired by the hurly-burly of protests, marches, demonstrations and organized political activities that made them feel as if they were helping to bring about important social change.

They also remembered being terrified.

Jenkins, a student body president at Howard University who had been on the SNCC executive committee, was thankful that he arrived in Mississippi in one piece. The Pennsylvania native, who had almost grown up in the civil rights movement by volunteering for the NAACP during high school, was traveling with fellow SNCC activists Charles Sherrod, Charles McDew and J. Charles Jones (the “three Charleses”) when the car carrying them accidentally ran over a dog in Alabama.

“The person who owned the dog complained that we had killed her dog, and a tremendous crowd surrounded us and demanded we had to pay for the life of this dog,” Jenkins says. “It was the first real confrontation I had in the South.”

He believes the incident could have had a much more violent result had it not been for a bystander—a retired judge who came to their rescue. “He indicated that there was no way we could’ve avoided hitting it and it wasn’t our fault,” says Jenkins. “Then he hustled us into our car and we drove away.”

Photo of Stephen Bingham by Tony Avelar

Not all of their colleagues were as lucky, as Bingham recalls. The Yale University student had been training in Ohio in preparation for the Freedom Rides in Mississippi. He remembers three fellow volunteers—James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner—leaving for the Magnolia State a few days before he was to depart. They were killed near the town of Philadelphia, Mississippi, by members of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Known as the Mississippi Burning case, the murders sparked national outrage and triggered a massive federal investigation that resulted in several convictions in 1967, as well as a belated one in 2005 for accused mastermind Edgar Ray Killen.

“That killing was intended as a message to the rest of us,” Bingham says. “They were telling us: ‘Y’all better not come down here.’”

But Bingham, Jenkins and the many others in their shoes weren’t deterred. They were driven by a cause greater than any single one of them, and they were determined to bring about change through legal means.

Perhaps it was destiny, then, that Bingham and Jenkins would become lawyers. “I never went into law with the hope of making lots of money,” Bingham says. “Instead, I began to see law as a tool for social change, and it was reinforced by the work that lawyers were doing concerning civil rights.”

Jenkins agrees, saying the civil rights movement “made it clear that law was a place of great impact on what happens in society. ... It was an easy thing for me to decide to become a practitioner.”

With political and social strife at the highest they’ve been in generations, several movement lawyers from the 1960s and ’70s believe they can use their life experience to educate and inspire today’s social activist lawyers and demonstrators.

Photo of Timothy Jenkins courtesy of Lauretta Jenkins

‘A SIGN OF THE TIMES’

After graduating from Yale Law School in 1964, Jenkins went about as far away from civil rights as a lawyer could.

In those days, Pennsylvania attorneys were required to do an apprenticeship, and his was at the Philadelphia firm of Norris, Green, Brown and Higginbotham. A former lawyer at the firm had joined the pharmaceutical company Smith, Kline and French Laboratories (now part of GlaxoSmithKline) and offered Jenkins a job. Newly wed and a father, Jenkins was looking for a steady income, so going to Smith Kline was a no-brainer. But it also affected his view of lawyers.

“It became clear to me that lawyers were not the movers and shakers I thought they were,” Jenkins says. “Lawyers are, typically, brought in at the tail end to clean up the details after major decisions have already been made. It really diminished my enthusiasm.”

Jenkins soon found himself gravitating back toward civil rights. Reflecting on his days with Norris Green, he realized that law could still be used as an instrument for shaping policy.

“Most of their practice was not focused on trying cases,” he says. “Instead, it was more about helping institutional clients and shaping their policies.” Jenkins took that model and used it to provide legal representation to organizations that had sprouted up in the civil rights era, including co-ops, housing and teachers’ groups and other professional organizations.

“When I graduated from Yale, I was coming out at a time when the Black Power movement was unfolding,” Jenkins says. “The black community was articulating its needs to have our own laborers, businesses, accountants, teachers unions and so on. I also did a lot of work in the South for farmers who wanted to create their own land development enterprises.”

Jenkins also helped found the National Conference of Black Lawyers in 1968. The organization’s initial clients included the likes of Angela Davis, Assata Shakur, members of the Black Panthers and several inmates from the Attica prison riots. He says that, between his own cases and the ones he worked on for the NCBL, there were times when he’d have as many as 300 cases going at once.

“Many of the clients I represented were cause-oriented, not just commercial or civic organizations but activist organizations,” Jenkins says. “I was never completely free of the activist orientation.”

Likewise, Bingham drifted toward radical causes after graduating from the University of California at Berkeley School of Law in 1969. He was selected as a Reginald Heber Smith fellow, awarded to top law grads to allow them to perform public service on behalf of the poor. It also allowed him to get creative with the way he took on cases.

“We were allowed to experiment with new forms of representation and not be in a straitjacket with traditional public assistance work,” Bingham says. Instead, he served as an in-house counsel with a tenants union in West Berkeley. “We were known as Tenants Organized for Radical Change in Housing, or TORCH,” he recalls with a chuckle. “I guess that was a sign of the times.”

Bingham also joined the National Lawyers’ Guild, where he found many kindred spirits. Through the guild, organized as a liberal alternative to the American Bar Association, one of Bingham’s most important relationships was with fellow radical lawyer Paul Harris.

Their friendship came in handy when Bingham was accused of smuggling a pistol into San Quentin State Prison in 1971 to his client, Black Guerrilla Family founder George Jackson. In the ensuing melee, Jackson, two other inmates and three corrections officers were killed while six inmates allegedly tried to escape. Bingham was charged for his role in what became known as the San Quentin Six case and, fearing for his life, decided to flee the country. After over a decade on the lam, he turned himself in. Bingham, whom Harris represented at his preliminary hearing, was acquitted in 1986.

Correction

Print and initial online versions of "Resistance Redux,” August, should have stated that six inmates at San Quentin State Prison allegedly tried to escape. It also should have stated that Paul Harris was Stephen Bingham’s defense attorney at his preliminary hearing but was no longer representing him at his acquittal.The Journal regrets the errors.

Clarification

“Resistance Redux,” August, should have stated that J. Tony Serra typically charges $25,000 for a death penalty case, knowing he could get nearly 10 times that working as a court-appointed attorney.

This article appeared in the August 2017 issue of the ABA Journal with the headline "Resistance Redux: Civil rights lawyers from the 1960s have lessons for today's social activists."

Write a letter to the editor, share a story tip or update, or report an error.