Sept. 29, 1982: 7 Deaths Point to Cyanide-Laced Pain Reliever

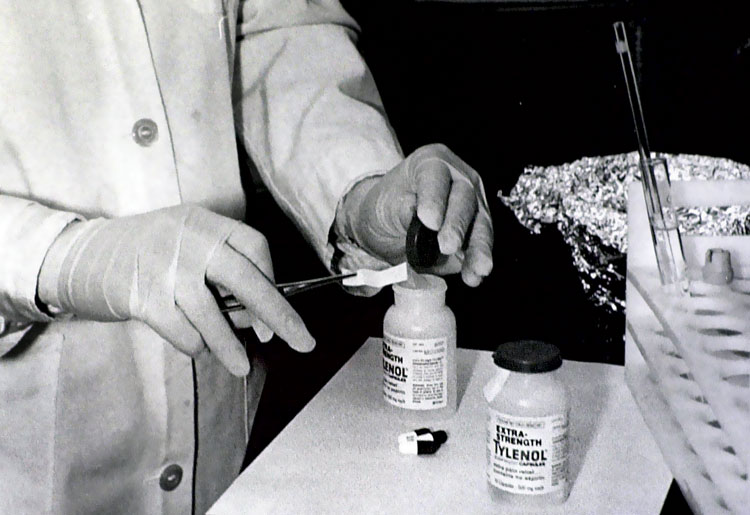

In 1982, bottles of Extra-Strength Tylenol are tested with a chemically treated paper that turns blue in the presence of cyanide. AP Photo

Mary Kellerman, a 12-year-old living in Chicago’s northwest suburbs, awoke one Wednesday morning with a headache and a sore throat. She walked to her medicine cabinet and grabbed a bottle of Extra-Strength Tylenol. Within seconds of taking two capsules, she fell to the floor, dead from what paramedics first thought to be a heart attack.

That same morning, across a suburban swath north and west of Chicago, others died in rapid succession: postal worker Adam Janus at home in Arlington Heights; a Winfield mother of four after a trip to the drugstore; a worker at a Lombard phone center as she left the restroom. And at Janus’ home later that same day, Sept. 29, 1982, his brother and sister-in-law also dropped dead—after complaining of headaches—while planning his funeral. By the time flight attendant Paula Prince expired in her Chicago apartment, the terrifying fact was apparent: People were dying from Tylenol laced with cyanide.

What ensued was something close to public panic. TV and radio exploded with any available fact or conjecture. Police cars with public address systems roamed Chicago, warning citizens not to ingest the popular pain reliever. Though Johnson & Johnson had helped rule out widespread adulteration of the product, the company recalled it anyway, while offering up a hotline and $100,000 reward.

Hundreds of investigators had converged on the metro area by the time a handwritten letter arrived at Johnson & Johnson headquarters a week after the first deaths. It read: “Since the cyanide is inside the gelatin, it is easy to get buyers to swallow the bitter pill. ... So far, I have spent less than $50 and it takes me less than 10 minutes per bottle.”

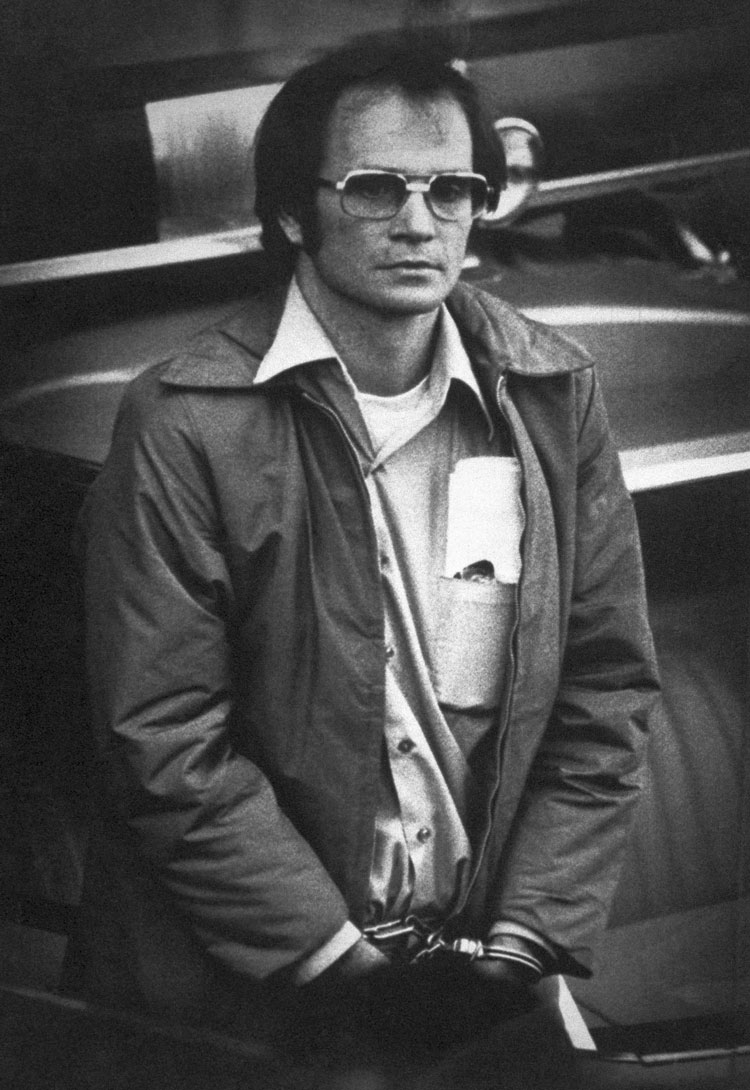

The letter demanded $1 million to stop the killings. The envelope was quickly traced to a defunct Chicago travel agency. After questioning the owner, investigators zeroed in on Robert and Nancy Richardson. She was a former employee who’d gone unpaid when the company folded; he was a husband who took abnormal interest in her claim. The two had disappeared from Chicago weeks before the Tylenol deaths, but evidence emerged that they were not who they pretended to be.

In Kansas City a few years earlier, James William Lewis and his wife, LeAnn, had been suspects in a neighbor’s death. He’d been charged, but the case was tossed because of flawed police procedures. Both were also suspected in a series of low-yield financial frauds.

The extortion letter placed them in New York City; and Lewis, the troubled child of migrant workers, seemed to enjoy the notoriety of a high-profile pursuit. As they moved between flophouse hotels, he wrote taunting letters to newspapers and, at one point, called a radio talk show. He was caught when recognized while reading Kansas City and Chicago newspapers at a New York library annex.

Though Lewis admitted penning the extortion letter, he was adamant that he had not committed the murders. He said the letter was intended to focus attention on his wife’s ex-employer and evidence that money had been diverted from travel agency bank accounts. Lewis was sentenced to 20 years in prison for the extortion attempt and an unrelated credit card fraud.

The Tylenol murders remain unsolved. Lewis, released in 1995, continues to be the prime suspect. In 2010, his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, was raided in search of new evidence. But in 2011, investigators gathered DNA from convicted Unabomber Ted Kaczynzki to determine whether he should be a suspect.

Still, the murders had an enduring impact on public health and perceptions of corporate responsibility. In 1983, Congress passed the Federal Anti-Tampering Act, making it a crime to interfere with consumer products. Johnson & Johnson’s response to the corporate nightmare, grounded in transparency and disclosure, became a model for modern crisis management. So successful was the company’s approach that it was later able to re-release Tylenol capsules in triple-sealed containers, now an industry standard.

Photo of James Williams Lewis by AP Photo.