California begins to release prisoners after reforming its three-strikes law

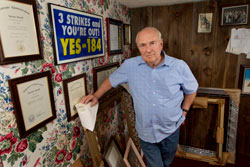

Mike Reynolds: “The full impact of Prop 36, either positive or negative, is really yet to be felt.” Photo by Norbert Von der Groeben.

In 1992, 18-year-old student Kimber Reynolds came home to Fresno, Calif., to be a bridesmaid. As she left a restaurant, two men rolled up on a motorcycle and tried to snatch her purse. When she resisted, one of them shot her. She died 26 hours later.

As the Reynolds family grieved, they learned that the shooter and his accomplice both had long rap sheets, largely for drugs and petty theft. Outraged that they had been freed, Mike Reynolds, Kimber’s father, wrote a proposed “three strikes and you’re out” law for repeat offenders.

Two years later, California passed that law, both as a ballot initiative and through the state legislature. Advertised as a way to keep violent recidivists off the streets, the three-strikes law doubled prison time for a second felony if there was a prior serious or violent felony, as defined by state law. Offenders with two serious or violent priors faced 25 years to life for the third “strike.”

But to qualify for the life sentence, that third felony didn’t have to be serious or violent. As a result, California began sentencing people to life for crimes like petty theft and drug possession. The law was challenged for 18 years, including two unsuccessful appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the meantime, second- and third-strikers made up roughly a quarter of California’s large prison population, straining the state budget. Advocates say 3,000 to 3,500 of California’s current third-strikers are serving 25 years to life for nonserious, nonviolent felonies. All of this may explain why 69 percent of Californians voted last year for Proposition 36, a ballot initiative that radically reformed the three-strikes law. Now, defendants may only be sentenced to 25 years to life if their crime was serious or violent, or they have disqualifying crimes—generally very violent crimes or sex offenses—among their priors. All other third felonies will be sentenced to double the time in prison, as if they were second strikes.

And more important, the law permits inmates who are already serving life sentences for nonviolent, nonserious crimes to petition for resentencing. As with new felonies, their new sentences would still be double the normal penalty for the underlying crime. But because such inmates have already served up to 19 years, resentencing usually means release from prison.

TRIAGE UNIT

Los Angeles County, the most populous county in the state and the nation, has by far the most prisoners eligible for resentencing. The Los Angeles Superior Court, the court of first jurisdiction, had received 1,389 petitions as of late October. To handle this flood, the county has set up a special system that consolidates all petitions under one judge, whose job is to handle nothing but resentencing of three-strikes prisoners until at least the end of this year.

The petitions are overwhelming all players in the county’s justice system. “Since Prop 36 passed, we get probably 150 calls a day,” says Harvey Sherman, a deputy public defender. (Though prisoners are not generally entitled to an attorney for post-conviction assistance, his office and many other California public defenders’ offices have agreed to represent three-strikes petitioners.)

“I would characterize it as an avalanche,” says Beth Widmark of the LA County district attorney’s Third-Strike Resentencing Unit.

Usually, petitions for resentencing would go to the judge who originally sentenced the defendant, or—because so many judges are retired—to one randomly selected. But the volume of Prop 36 petitions got to be too much for the leaders of the superior court, so they decided to consolidate the petitions under a single judge.

The job went to Judge William Ryan, who was already the go-to judge in the county for writs of habeas corpus. He says this isn’t the first one-judge system for handling special cases. After the 1990s Rampart scandal, in which corrupt Los Angeles police officers admitted to framing defendants, thousands of petitions for writs of habeas corpus were consolidated in front of one judge.

Sherman, whose Public Integrity Assurance Section was founded in response to the Rampart incidents, says 130 petitioners were ultimately freed in those cases. But under Proposition 36, there are already far more: As of late October, 263 prisoners had been resentenced in Los Angeles County alone. Furthermore, there’s a two-year deadline hurrying the petitions; eligible prisoners must show good cause if they file later.

Another reason the system is overwhelmed is the huge amount of paperwork each case generates. In addition to determining whether to disqualify prisoners with certain priors, Proposition 36 requires Ryan to decide whether the petitioner poses a threat to society. The average time served by the county’s petitioners is 14 years, Ryan says, leaving a backlog of more than a decade of records for each inmate. All must be carefully reviewed, particularly by prosecutors deciding whether to oppose a petition. Each petition requires a response within 45 days, so Widmark’s unit must respond to between 70 and 100 cases a week.

Because neither Proposition 36 nor state law provided a clear system for handling the petitions, Ryan says, the first thing he did after his November 2012 appointment was to agree with the prosecutor’s and public defender’s offices to treat them as if they were habeas corpus petitions.

Then, he says, the parties “triaged” the petitions: They moved those that were unopposed by prosecutors to the front of the line, with the goal of clearing those out quickly.

PATIENCE TESTED

It hasn’t gone as quickly as hoped. At a morning of hearings in mid-August, the court was still hearing unopposed petitions. Ryan says the average time from petition to resentencing in Los Angeles County is 148 days. He will be working on the cases until all are completed, unless the hearings become overwhelming. In that case, the superior court has authorized adding additional judges to the project.

“Some inmates are getting impatient,” Ryan says. “They didn’t use violence when they committed their crime, so they thought the doors of the prison should swing open” the day after voters approved Prop 36.

Discussion at those August hearings focused mainly on the defendants’ re-entry plans. Ryan emphasizes that success after prison, particularly in the first 90 days, depends largely on access to food, housing, jobs and addiction treatment, if applicable. (It often is; Ryan says that 37 percent of his petitioners’ life crimes were tied to drug crimes, and 56 percent more were property crimes that were likely related to drugs.)

“Before resentencing, they have to lay that out for me,” says Ryan. “When they release them, they give them $200 and a bus ticket and say, ‘Good luck.’ And that’s not necessarily the most humane thing to do.”

Because other counties are already hearing opposed petitions, the California appeals courts have begun to consider some of the gray areas in the law. That includes two cases from San Diego that raise the question of whether possession of a firearm by a felon is the kind of serious, violent crime that disqualifies the defendant from resentencing.

THE NEXT STAGE

Thus far, those who have been released have largely stayed out of trouble. The county probation department is supervising only 28 of the 200 people released in the county, but a representative said in mid-August that only two had been arrested again. If that’s every new arrest, it’s a minuscule recidivism rate.

Statewide, a study by the Stanford Three Strikes Project, a law school initiative advocating three-strikes sentence reductions, found a 2 percent recidivism rate in September, when prisoners had been out an average of 4.4 months. That study reported the average recidivism rate after 90 days—the crucial period during which people are most likely to re-offend—for non-Prop 36 prisoners was 16 percent.

But Reynolds, the father of the slain bridesmaid and a driving force behind the three-strikes law, says it’s too soon to determine if that reform has worked.

“The full impact of Prop 36, either positive or negative, is really yet to be felt,” he says. “Only a handful [of offenders] have really come out in comparison to the full number. Once they are fully released, the real question is: Now what happens?”

This article originally appeared in the December 2013 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “After Third Strike, Many Now Walk: California begins to release prisoners after reforming its three-strikes law.”

Correction

Print and initial Web versions of "After Third Strike, Many Now Walk," December, should have stated that Judge William Ryan was appointed to handle Proposition 36 petitions in November 2012. The article also mistakenly reports that Ryan's appointment ends Dec. 31. He is assigned the cases until all are completed. And if the hearings become overwhelming, the Los Angeles Superior Court has authorized adding additional judges to the project.The ABA Journal regrets the errors.