Brain Trials: Neuroscience Is Taking a Stand in the Courtroom

Illustration by Elizabeth Traynor

Six weeks after getting his driver’s license, Christopher Tiegreen—a friendly, outgoing 16-year-old who played soccer and sang in his high school chorus—was in a car collision near his home in Gainesville, Ga. Tiegreen’s Isuzu Trooper flipped several times, causing severe head injuries. He was taken by helicopter 50 miles to a hospital in Atlanta, where doctors told his mother he might not make it.

A month later, Tiegreen emerged from a coma a different person. The impact of the crash caused damage to the frontal lobe of his brain and sheared his brain stem. During his recovery and rehabilitation, the usually gentle Tiegreen became violent toward his mother, as well as with other family members and rehab staff. His family sent him to live in various residential facilities, but he frequently was expelled for inappropriate behavior.

On Sept. 11, 2009, Tiegreen, then 23, walked out of a duplex apartment where he was supposed to be under 24-hour supervision. In a yard nearby he attacked a young woman holding her 20-month-old son. He was charged with aggravated assault, criminal attempt to commit a felony, false imprisonment, battery, sexual battery and cruelty to a child in the third degree.

Tiegreen’s lawyer sought to have him declared mentally incompetent. His mother told a jury about his brain injuries and insisted he was incapable of assisting in his own defense. A neuropsychologist for the defense testified that Tiegreen suffered severe brain impairment. But the state presented a psychologist who said that Tiegreen was focused and cooperative, and that he understood the proceedings against him. The jury found Tiegreen competent and, after losing an appeal, his lawyer has taken the case to the Georgia Supreme Court, which at deadline had not yet responded to the petition. Tiegreen’s mother, Laura Howell, was astonished that her son was declared competent. The courts, she says, need to better understand the nature of her son’s brain injury and its effects before weighing his legal competency and, ultimately, the extent of his culpability.

“I thought the legal system had a better sense,” says Howell, a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology. “There’s a big crack that people with brain injuries fall into. It’s so narrow in the legal sense that it doesn’t leave room for people like Christopher.”

The case illustrates one of the challenges that lawyers, judges and defendants face in cases that bring together neuroscience and the law, where trying to explain the brain and human behavior can clash with how the legal system determines culpability, competency and the manner in which such cases should be handled. Defense lawyers are increasingly introducing high-tech brain images and citing studies that link brain injury and violence to explain, excuse or mitigate criminal behavior.

‘PROMISE AND TERROR’

Organizations such as the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Law and Neuroscience—a cooperative of scientists, lawyers and researchers seeking to better understand this intersection of modern neuroscience and criminal law—are helping to sort through the morass. The network, funded through a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, is headquartered at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., and led by Owen Jones, a professor of law and biology at Vanderbilt.

“There has been a growing use of neuroscience and the law, and one of the questions we have is how to interpret the neuroscience in a way that’s appropriate,” Jones says. “It’s one of those things that holds both promise and terror for the legal system.”

Jones warns that neuroscientific evidence must be viewed and interpreted cautiously. “Once you start going down this path that there’s this quirk in the brain that makes me not responsible for my actions, that makes people understandably concerned,” he says. “It has to be weighed with other evidence.”

The network is supporting research to examine questions such as whether brain-imaging techniques can reveal a person’s state of mind, and whether such images can detect memory or deception. Is it possible to know what was going on inside a defendant’s head at the time of a crime or whether that person could regulate or control their criminal behavior?

Stephen J. Morse, a professor of law and psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania and a member of the research network, has long argued that brains don’t commit crimes; people do. Morse says that even the latest neuroscientific research and imaging techniques cannot answer questions about responsibility and competence. “Today, I think that neuroscience has added virtually nothing really relevant to criminal law,” he says.

The problem, he says, is that some lawyers are making giant leaps from the science. “In the literature, lots of people are making extravagant claims about what it can do for us. They’re based on insufficient or irrelevant science, or people are making moral inferences that the science does not entail,” he says.

Morse is referring to some of the studies that statistically link brain damage with criminal or aberrant behavior but, in his view, fail to take into account myriad other factors that can contribute, including environmental factors. It’s not that Morse doesn’t believe brain damage can cause people to lose their judgment and inhibitions. His point is that we don’t know whether or how those people try to control their impulses. “Causes are not excuses,” he says.

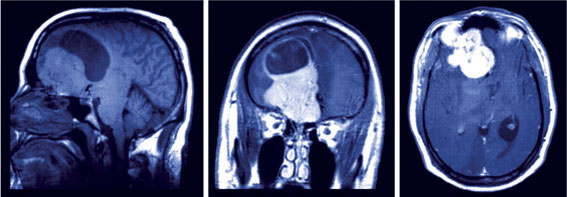

The brain scans of the 40-year-old schoolteacher.

Take the case of a 40-year-old married schoolteacher from Virginia who during the year 2000 inexplicably began to have a sexual interest in children. He surreptitiously collected and viewed child porn on the Internet and was convicted of trying to molest his stepdaughter. The night before sentencing, he complained of horrible headaches. At the hospital he talked of suicide, made sexual advances to staff, spoke of raping his landlady and urinated on himself.

An MRI revealed that the teacher had a large orbitofrontal tumor, a growth on an area of his brain associated with social behavior. After surgeons removed the tumor, he was no longer considered a threat and completed a sexual rehab program. But a year later, he began getting headaches and once again collected pornography. Another MRI showed the tumor had regrown, and it was removed again.

Dr. Russell Swerdlow, a neurologist who treated the teacher at the hospital and later wrote about the case in the Archives of Neurology, says that such radical behavioral changes are not surprising. “But it was the first case in which the bad behavior was pedophilia,” says Swerdlow, a neuro-scientist and professor at the University of Kansas. “What was so striking about this was his inability to act on his knowledge of what was right or wrong.”

Swerdlow says when pathways are broken between the orbitofrontal lobe and the amygdala, a part of the brain involved in emotional responses and decision-making, the result can be impulsive behavior. “You don’t get the feedback that controls your decisions. You don’t have the brakes on your behavior,” he says.

Morse says that while the teacher may deserve some mitigation in sentencing because of his ailment, it’s not clear whether he lacked the ability to control his impulses, or simply chose not to. “People want to say his tumor made him do it. He made him do it. There is always a reason people do it,” Morse says. “We don’t give a pass to the other pedophiles. He felt an urge, which he understood and did not resist, but acted on it.”

While it’s true that not everyone who suffers brain damage commits criminal acts, there are plenty of anecdotal cases in medical literature showing that it causes behavioral changes, including impulsiveness, depression, aggression, inappropriate sexual behavior, lack of thought control and violence among people who prior to their injuries did not exhibit such behaviors. But how that should be considered in criminal culpability—and what science can truly explain—remains murky.

The brain scans of Herbert Weinstein.

That hasn’t stopped defense attorneys from trying to introduce evidence of damaged brains into the courtroom, including brain scans. One such case, frequently cited in law and neuroscience journals, is that of New York advertising executive Herbert Weinstein, 65, who was arrested on charges that he strangled his second wife, Barbara, and threw her out the window of their 12th-floor Manhattan apartment in 1991 during an argument about their children.

Weinstein never denied killing his wife. His lawyer, Diarmuid White, argued that Weinstein was not himself due to an arachnoid cyst on his brain. White contended that the cyst caused pressure on part of Weinstein’s temporal lobe, compromising his self-control and emotional regulation.

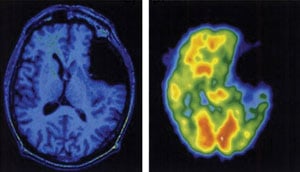

“It was a very violent crime, and it was completely inconsistent with his whole life and personality,” recalls White, now retired. “He was very amiable and well-liked. The conduct just didn’t fit his personality.” White sought to introduce brain images taken by positron-emission tomography to show the cyst and reveal metabolic imbalances in Weinstein’s brain. These images, he argued, were evidence that Weinstein’s power of reason was impaired. The judge decided to allow evidence that the brain cyst existed, along with the images, but not that the cyst caused Weinstein to act violently. “I thought once a jury saw that PET scan with that big, black hole in the brain, they won’t convict him,” White says.

Daniel Martell: “Lots of people ooh and aah at the pictures. It doesn’t tell you anything about a person’s behavior.” Photo by Jonah Light.

THE CHRISTMAS TREE EFFECT

Daniel Martell, a forensic neuropsychologist who examined Weinstein and testified for the prosecution, says the brain images were nothing more than fancy pictures meant to stir a jury. “It was the Christmas tree effect,” Martell says. “Lots of people ooh and aah at the pictures. It doesn’t tell you anything about a person’s behavior.”

Martell says Weinstein’s brain was functioning fine. “Just because he had the giant cyst didn’t make any difference,” Martell says. “There was no other evidence of out of context or aberrant behavior.”

Zachary Weiss, the New York City district attorney who prosecuted the case, thought it was simply a matter of a man getting angry at his wife and killing her. That was until White sent him the brain scan during discovery. “I got this picture in the mail and thought you’ve got to be joking,” Weiss recalls. “It got complicated. I called this the rich man’s defense.”

Weiss never bought the theory that the cyst on Weinstein’s brain led him to commit murder, but he didn’t want to take the risk of letting a jury decide after seeing those brain images. He agreed to a plea deal in which the charges would be reduced to manslaughter with a sentence of seven to 14 years. “I think I did win in the sense that I didn’t want that picture shown to a jury,” he says. “In the end, I think we got it right. It was a manslaughter case.”

Whether Weinstein’s brain made him do it or not, Weiss believes the case was important. “It opened up a debate academically about responsibility and free will, and how we evaluate scientific evidence,” says Weiss, now a Social Security administrative law judge.

Weinstein served 14 years in prison before being paroled in 2006 and was, according to testimony during a parole hearing, a model prisoner who tutored other inmates and showed no further violent tendencies. He died in 2009.

Twenty years after the case, Martell still believes brain scans don’t explain specific behaviors. “The problem is that the science has not come along to support what the scan means,” says Martell, now a Newport Beach, Calif.-based consultant for criminal as well as civil cases. “Since the ’90s, we’ve been much better at generating the cool pictures than we are at explaining what they mean.”

Yet lawyers are hopeful. Nita Farahany, a professor of law and genome sciences and policy at Duke University, has been tracking criminal cases in which lawyers have introduced neuroscientific evidence since 2004. By combing legal opinions, she’s found about 2,000 examples, with 600 of those cases in 2011 alone. “It’s increased exponentially,” Farahany says. “And my database doesn’t even include cases that are settled before trial or never get to the appeals process.”

Farahany found neuroscientific evidence was most often used for capital mitigation, followed by competency hearings; the rest was presented during the guilt phases of a trial. She says about 20 percent of trials in which such evidence was used resulted in “favorable outcomes” for criminal defendants, which includes reduction of charges or sentences. “In some cases, the introduction of neuroscientific evidence has mitigated the extent of a defendant’s liability, but I am not aware of a case in which such evidence has exonerated a criminal defendant,” Farahany says.

The question of legal competency for those with brain injuries, such as Tiegreen, is an area that deserves greater scrutiny, Farahany asserts. Brain-injured defendants may not fit the standard definition. It may be something like they have poor memory, are more impulsive than most, or are unable to exercise sound judgment, she says. In these cases, the ability of the criminal defendant to assist in their own defense is really quite limited. And yet this isn’t the way courts traditionally approach competency.

Laura Howell: “In a lot of ways, he’s not my son. He used to be so loving. … People don’t understand.”

Photo by Stan Kaady.

SUPPORT FOR VETERANS

Among the growing number of cases involving neuroscientific evidence are those that involve combat veterans from Afghanistan and Iraq as defendants. The attorney for Army Staff Sgt. Robert Bales, who was charged with killing 17 civilians in Afghanistan, has said his client suffered a traumatic brain injury.

So many veterans are winding up in the courts that the National Veterans Foundation, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit, created The Attorney’s Guide to Defending Veterans in Criminal Court, which covers traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Dr. Chrisanne Gordon, a Columbus, Ohio, rehabilitation medicine specialist who works with brain-injured vets, is one of three authors who wrote a chapter about traumatic brain injury. “They’re not insane, they’re not retarded, but they frequently have issues with impulse control and fall through the cracks of the legal system,” she says.

Two years ago, while Gordon was screening vets for TBI, she got a call from a mother whose son, Andrew Chambers, pleaded guilty in 2008 to felony assault charges and was sentenced to 10 years in prison. Chambers’ mother, Rebecca Cramer, was enraged because she thought his lawyer rushed him into a guilty plea without exploring a possible defense based on PTSD or brain injury.

“Nothing seemed right about the case,” Gordon says. “He had multiple instances of head injury. He was in an explosive ordnance division. He had 12 concussion injuries and the VA never diagnosed him as having traumatic brain injury.”

Gordon visited Chambers in prison and examined him. She said he showed signs of traumatic brain injury, including memory lapses, trouble focusing, headaches and trouble making decisions.

Cramer noticed right away that her son was not himself when he returned from Iraq in 2005. He withdrew from his family and began drinking and taking drugs, she says. “His temper was so crazy, I asked him to leave. You could tell that the light had gone from his face.”

Chambers got into a fight with a man over money he owed, and the man pulled a knife. Chambers pulled a gun. During a struggle, his gun fired a round into the floor. Chambers did not dispute what happened and pleaded guilty. He later appealed the case, claiming that he did not make the plea agreement voluntarily, or intelligently, because of his mental state, and that he was misled by his attorney into thinking he would receive no more than five years. But Ohio’s Fifth District Court of Appeals dismissed his claims. His mother wants to take the case further but has been unable to afford to hire a lawyer.

Disturbed by such cases, Gordon has become part of a movement to create more special veterans courts, a concept that began in Buffalo, N.Y., in 2008. The more than 80 such courts established since then recognize that vets have mental health issues related to their combat and try to promote rehabilitation rather than incarceration. (See “The Battle on the Home Front,” ABA Journal, November 2011.)

One of Gordon’s biggest allies in Ohio is state Supreme Court Justice Evelyn Stratton, who plans to work full time with veterans’ justice issues after she retires later this year. She supports the development of more veterans’ treatment courts and hopes to change sentencing guidelines to ensure judges in all courts look at a defendant’s military service record. “We want them to look at war experience as mitigation,” she says. “And we want them at least to look at the causes of what happened.”

Gordon says failure to recognize traumatic brain injuries, or to bring evidence of them in court, is harming many more veterans like Chambers. “We’re talking about a guy whose brain is as confused as possible,” she says.

EMERGING NEUROLAW

Legal experts expect many more such cases to crop up, not just among veterans but among all criminal defendants who believe that brain science can help better explain, and possibly mitigate, their behavior.

Recognizing the growing need for professionals to better understand these issues, the University of Wisconsin in Madison launched a dual degree program this year in neuroscience and law, joining Vanderbilt among the few universities offering such specialties.

“It seemed like a natural thing to do,” says Pilar Ossorio, a professor of law and bioethics at UW-Madison. “We want them to question the uses of neuroscience and to be able to create and design experiments in neuroscience that can help us answer some of these questions with the law. These are all questions that are fundamental to the law and up to now have been based on commonsense assumptions about the legal system.”

Tiegreen’s case may be the best illustration of where law and neuroscience need to work together, which is not to try to explain or excuse criminal behavior, but to evaluate each defendant and customize a plan that serves their mental health needs as well as the need to keep the public safe.

That’s what neuroscientist and best-selling author David Eagleman has been advocating. Eagleman, who directs Baylor College of Medicine’s Initiative on Neuroscience and the Law, believes that it doesn’t make sense to try to determine blameworthiness, or to ask whether a person’s brain or the person is at fault.

“The brain is an enormously complicated system, and there are a vast number of factors that influence who you are and how you behave,” he says. “People become who they are from a complex interaction of their genes and all of their experiences—from what happens in the womb, to the neighborhood you grow up in, to the culture in which you’re embedded.”

Attempting to assign retrospective blame for criminal behavior, according to Eagleman, is pointless. “Forget all that. The important thing is where we go from here. How can we help?” he says.

“Having special court systems, mental health courts and recognizing the importance of mental health issues is where we need to go.”

Eagleman’s program at Baylor is focused on how advances in neuroscience can help guide the creation of new laws, how criminals are punished, and how we might develop rehabilitation programs through learning from technologies such as real-time brain imaging. The idea is to make the intersection of neuroscience and criminal law meaningful.

That’s the kind of approach Tiegreen’s mother would like to see the legal system take as she continues to seek a fair resolution of her son’s case. “I grasp the concept that he committed a crime,” she says. “But what are our options? Where does he go?”

Tiegreen has been in jail for two years awaiting trial. “This is a kid who grew up in a nice, middle-class home,” his mother says. “But in a lot of ways, he’s not my son. He used to be so loving. His brain is so screwed up. People don’t understand. It’s not that Christopher is mean or cruel. It’s that he can’t control himself like me or you.”

Related articles:

ABA Journal: “Defending the Defenders: New Guide Covers How to Defend Veterans with Invisible War Wounds”

ABA Journal: “The Battle on the Home Front: Special Courts Turn to Vets to Help Other Vets”

Kevin Davis is a freelance journalist based in Chicago and the author of Defending the Damned.