America's Magna Carta

The copy on display in Boston has been in the possession of Lincoln Cathedral in the United Kingdom since 1215. On June 15 of that year, King John of England met with his rebellious barons at Runnymede, a meadow along the banks of the Thames River west of London, to resolve a power struggle that threatened to start a civil war.

It’s safe to say that neither the king nor his nobles had any appreciation for the long-term implications of what they accomplished in that English meadow 800 years ago. In many ways, the Magna Carta was a product of its time and place, addressing some of the practical concerns of the power elite in a medieval kingdom at the edge of Europe. But over centuries of interpretation and application, the Magna Carta came to stand for some of the most important principles of individual liberties and limits on government power that support constitutional democracy in the United States and other countries around the world.

“When I have my students read Magna Carta, it’s amazing how much still resonates in our rights today,” says Joyce Lee Malcolm, a law professor at George Mason University. “Magna Carta is still the source for the ideas expressed in the Constitution.”

Numerous copies, or exemplifications, of the Magna Carta were produced for distribution throughout King John’s realm, which included parts of France and much of the British Isles. But in addition to the Lincoln Cathedral’s copy, only three other exemplifications of the 1215 Magna Carta still exist. One is owned by Salisbury Cathedral, and two are on display at the British Library in London. Twenty copies of other versions produced between 1216 and 1300 are known to exist. One is a copy written in 1297 that is owned by an American lawyer and displayed at the U.S. National Archives in Washington, D.C. All the others are in Australia or the United Kingdom.

One of those copies, dating to 1300, was discovered last December in the town council archives of Sandwich, a village in southeast England. Even though the document was described as “rotten and soggy,” with a piece missing, it has been valued at some $15 million.

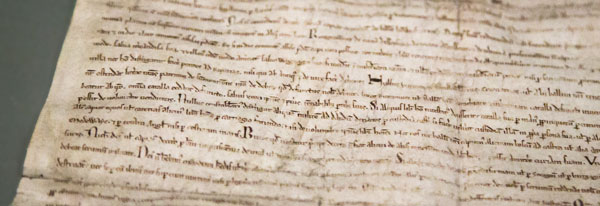

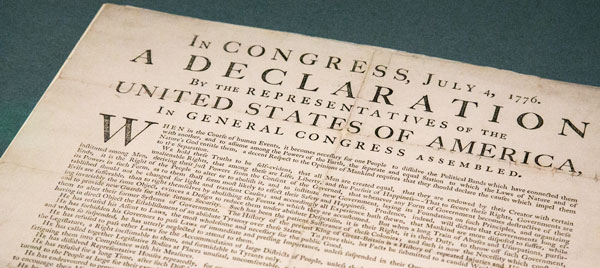

Photo of the Magna Carta on loan for last year’s exhibit in Boston by Kathy Anderson

A HUMBLE VISAGE

At first glance, at least, the Magna Carta really isn’t much to look at. Like all the surviving copies, the exemplification on display at the Museum of Fine Arts (later at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, and finally at the Library of Congress in Washington) was not particularly large—about 18 inches square—and its writing —slightly less than 4,000 words, all in Latin—has dimmed with age. The words are small, as if the scrivener was concerned that it might not all fit onto one sheet. The charter has none of the decorative filigree so common to medieval documents, and even the seal of King John is missing.

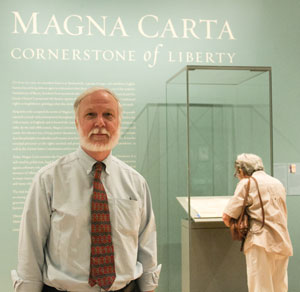

And yet the Magna Carta’s hold on visitors as they edged toward the glass case that held it was undeniable. The charter “is very plain, which kind of increases its power,” says Gerald W.R. Ward, a senior curator emeritus of American decorative arts and sculpture who coordinated the exhibition, “Magna Carta: Cornerstone of Liberty,” which was co-sponsored by the MFA and the Massachusetts Historical Society. “Its impact is belied by its appearance. The guards have told me some people get misty-eyed and break into tears.”

It should come as no surprise that the Magna Carta can have that effect. To view a copy of the Great Charter is to look back through 800 years of history into what legal experts say is perhaps the earliest written source of the principles that provide the foundation for the rule of law in the modern world. And the Magna Carta may be even more important to the development of individual rights under the constitutional system that developed in the United States than it is to the parliamentary structure that evolved in the United Kingdom.

It is, perhaps, the visual reality of the Magna Carta’s antiquity that helps convey its meaning to Americans, whose history as settlers of the New World from Europe didn’t start until the charter had already been in existence for some 400 years.

“As Americans, we value Magna Carta tremendously as the first in a long line of documents that protect our liberties,” says Nathan Dorn, the rare book curator at the Law Library of Congress, who coordinated the library’s exhibit, “Magna Carta: Muse and Mentor,” which closed in January. The exhibit featured the same copy of the Magna Carta that was on display in Boston. The charter was then returned to Britain, where it was displayed for several days with the other surviving 1215 copies at the British Library in London. “When we look back at Magna Carta, it’s an obvious grandfather for all of our own documents stating our liberties.”

Gerald Ward: “Its impact is belied by its appearance. The guards have told me some people get misty-eyed and break into tears.” Photo by Kathy Anderson.

THE MYTH LINK

Part of the draw also is a matter of mythology, which gives documents meaning that goes beyond their original intent, says A.E. Dick Howard, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law and an expert on the Magna Carta whose books include The Road from Runnymede: Magna Carta and Constitutionalism in America, published in 1968.

“Magna Carta has had a remarkable capacity to be relied upon and invoked over the centuries by lawyers and judges,” says Howard. “Magna Carta was a convenient starting point for so many concepts. Among those ideas, he says, “Magna Carta is the perfect foundation for the argument for a super-statute of superior law,” an idea that carried over to the creation of the U.S. Constitution.

As the American colonies began to move inexorably toward independence from Britain in the 18th century, the Magna Carta gave them support for the idea that some laws may be beyond the power of both monarch and parliament.

“Magna Carta really has more meaning here than it does in its country of origin,” says Howard. “There’s more Magna Carta in American constitutional law than in the U.K.”

Stephen J. Wermiel, a law professor at American University, agrees that myth and symbolism are important to the Magna Carta’s role in American law. The document’s impact on the jurisprudence of the U.S. Supreme Court, for instance, “is more symbolic than substantive,” he says, but that symbolism includes ideas of government accountability, checks on government power and due process. “Those things contributed to constitutional development,” he says.

“I don’t think Magna Carta really reflects our rights-oriented society, but it might be a case of the myth being more important than the reality,” says Wermiel, who covered the Supreme Court for a dozen years as a reporter for the Wall Street Journal. “We think our culture of rights has this great pedigree. Magna Carta has taken on a larger-than-life existence because of the things we’ve traced back to it.”

Some experts on the other side of the Atlantic share those views. “Americans are much more enthusiastic about Magna Carta, as they are about everything. The British take it more for granted,” says Nicholas Vincent, a professor of medieval history at the University of East Anglia in Norwich. Vincent is the principal investigator for a research project funded by the U.K. Arts and Humanities Research Council that is seeking to track down lost original copies of the Magna Carta, learn more about King John, and create an online database of commentary, images and research findings about the charter. He also is the general editor of Magna Carta: The Foundation of Freedom 1215-2015, released last year by Third Millennium Publishing in London to help commemorate the charter’s 800th anniversary.

Illustration by Stephen Webster and Brenan Sharp

It’s not that the Magna Carta has been forgotten in Britain. Sir Robert Worcester, a deputy chair and trustee of the Magna Carta Trust in the United Kingdom who chairs the Magna Carta 800th Committee, describes the charter as “England’s greatest export,” which has come to stand for a number of fundamental legal principles: due process of law, the supremacy of the law above even monarchs, justice delayed is justice denied, and no taxation without representation.

“Some people have said to me, ‘Ah, it’s just about the barons and their taxation,’ ” said Worcester, who was born in Kansas City, Missouri, in an interview with the British newspaper the Telegraph in January 2014. “And I say, ‘Yes, and much later it was called no taxation without representation, and England lost a colony called America on that basis.’ The relevance of the Magna Carta in the 21st century is that it is the foundation of liberty, some say the foundation of democracy.”

And yet Worcester wonders why there is no British memorial or visitor center at Runnymede, although he is leading a push to raise enough funds to have one built. The only recognition of that fateful meeting between King John and his barons in 1215 is a simple monument that was constructed in 1957 by the ABA. That monument will be rededicated June 15 at the close of the ABA’s London Sessions, which also will include a series of substantive programs, ceremonies and social events to help mark the Magna Carta’s 800th anniversary.

The London Sessions will be the culmination of a yearlong commemoration of the Magna Carta by the ABA to emphasize its legacy and continuing importance. The anniversary “is the best opportunity in our lifetime to celebrate and explain the rule of law in the United States and the world,” says Stephen N. Zack of Miami, a past ABA president who chairs the association’s Magna Carta 2015 Committee and the Rule of Law Initiative. “Magna Carta is the very basis of the rule of law.”

Magna Carta: Symbol of Freedom Under Law received a first place honor in the 36th annual Telly Awards this year.

‘THE GOOD OLD LAWS OF THE PAST’

Surveys conducted in recent years by Market & Opinion Research International, a British polling company founded by Worcester, determined that more Britons have heard of the American Declaration of Independence than the Magna Carta, and that only one in five survey respondents were able to give the correct date and place where the Magna Carta was negotiated, and identify which monarch put his seal to it.

Even British Prime Minister David Cameron was stumped when, during an appearance on the Late Show with David Letterman on Sept. 26, 2012, the host asked what the title of the Magna Carta was in English. As Cameron sat perplexed, Letterman said, “Boy, it would be good if you knew this,” and informed Cameron after a commercial break that the answer was the Great Charter.

But how the Magna Carta is viewed in Britain relates to much more than opinion polls and television faux pas. In the context of Britain’s long history, the Magna Carta stands for vital legal principles, but it is not necessarily viewed as the primary source of those principles.

“What King John offered to do in 1215 was not to create a written constitution but to defend and uphold law, liberties and customs already considered ‘just,’ ‘good’ and perhaps above all ‘ancient,’ ” writes Vincent in Magna Carta: The Foundation of Freedom. “Magna Carta was intended not to make new laws but to ensure that respect was paid to the good old laws of the past,” primarily Anglo-Saxon times that preceded the Norman invasion by William the Conqueror in 1066. “To this extent, it was not the foundation of English law but an attempt to preserve or restate something regarded as much more ancient and binding.”

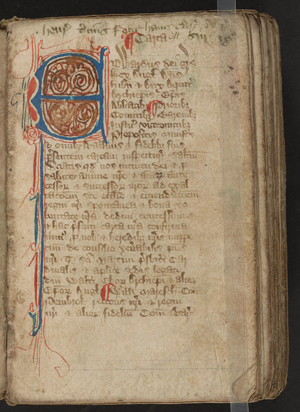

One of the Law Library of Congress’ most treasured items is this miniature manuscript, graced with intricate colored pen work, which contains the text of the Magna Carta, the Charter of the Forest and the 13th-century statutes of England. Photo courtesy of the Law Library of Congress.

By now, only three of the 63 chapters in the original Magna Carta (reduced to 37 by 1225) remain in the statutes of the United Kingdom; all the others have been repealed by Parliament. The three survivors secure the freedom of the English church (Chapter 1); guarantee the “ancient liberties” of the city of London (Chapter 9); and set forth the right to due process (Chapter 29, consolidated from Chapters 39 and 40 in the original charter), although the charter never actually used the term due process.

Chapter 29 is the key. It states: “No free man shall in future [language added after 1215] be arrested or imprisoned or disseised of his freehold, liberties or free customs, or outlawed or exiled or victimized in any other way; neither will we [“we” refers to the king] attack him or send anyone to attack him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land. To no one will we sell; to no one will we refuse or delay right or justice.”

These provisions, Vincent says, “were not just bolt-ons to a settlement between king and barons,” nor were they statements of rights that applied only to the barons in their relationships with the king. “The barons had to abide by them as well.”

But what the Magna Carta became is not necessarily what it started out to be, according to a leading constitutional scholar in the United States. “I don’t know what the hell Magna Carta says; it’s like Latin,” said Akhil Reed Amar, a professor of law and political science at Yale University, in a lecture at the Library of Congress to mark Constitution Day on Sept. 16, 2014. “We read ‘law of the land’ into it, and ‘due process,’ but that came later. In 1215, it wasn’t about jury trials or ordinary people. Later generations would reinterpret Magna Carta in some very interesting ways, just as we later reinterpreted the Bill of Rights. It may not matter that Magna Carta was not originally about jury trials. It came to be about that.”

The first century of the Magna Carta’s existence was action-packed. True to his reputation as one of the cruelest, most devious and incompetent monarchs in British history, King John had the charter invalidated by Pope Innocent III only a few months after placing his seal on it. But after John’s death in 1216, the charter was reissued, in a shortened version, with the seals of a papal representative and the regent to King Henry III, who was 9 years old when he succeeded his father. The charter was reissued again in 1217, 1225 and 1297—the final version that was entered at the head of England’s statutes.

But then the Magna Carta slipped into relative obscurity—to be cited now and then in various disputes between Crown and Parliament—especially during the Tudor dynasty, a period, by coincidence, of relative stability and growth for Britain that ended with the death of Queen Elizabeth I in 1603.

Etching of Sir Edward Coke by Shutterstock.com

THINGS GO BETTER WITH COKE

It was not coincidence that interest in the Magna Carta and what it meant in terms of individual liberties and limits on government powers was revived during the turbulence of the Stuart dynasty in the 17th century, which resulted in a civil war, the public execution of Charles I in 1649, the reign of Oliver Cromwell as lord protector (a virtual dictatorship) and the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. In 1689, the English Bill of Rights was adopted as part of the Glorious Revolution that brought William III and Mary II of the Dutch House of Orange to the British throne. The Bill of Rights helped shift power from the monarchy to Parliament.

Two of the most influential legal thinkers in British history—Sir Edward Coke (1552-1634) and Sir William Blackstone (1723-80)—played key roles in the re-emergence of the Magna Carta as a statement of rights and liberties.

Coke enjoyed a long and illustrious legal career as a lawyer, and he served in both Parliament and as chief justice of the King’s Bench under Charles I. He was a particularly strong advocate of the English common law and the idea that the Magna Carta reconfirmed ancient common-law traditions and natural rights that existed before 1215.

Coke’s view of the common law as an evolving set of principles provided crucial support to the ideas expounded by the American colonists, and it still echoes in our modern constitutional jurisprudence. “Coke has a wonderful defense of common law,” says Malcolm of George Mason University, “that it came through custom and was preserved generation after generation after generation, to be continued in new contexts.”

These ideas played out dramatically in the Five Knights Case of 1627—a tax dispute. Seeking to raise revenue to support various domestic and foreign policies, Charles I “invited” his subjects, without the endorsement of Parliament, to contribute higher amounts to the royal coffers. Many who refused were imprisoned. Five knights who were jailed issued legal writs of habeas corpus to seek bail, invoking the Magna Carta’s assertions that “no free man” shall be imprisoned “except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land,” and that justice will be denied or delayed to no one. When bail was refused to one of the knights, Coke stepped in to provide a defense.

In his Petition of Right (1628), Coke described the Magna Carta as a statement of the rights of free-born Englishmen rather than simply a description of the relations between the king and his barons. In a speech to Parliament, Coke emphasized limits on royal power when he made his famous statement that “Magna Carta is such a fellow that he will have no sovereign.”

Coke’s analysis was crucial to the Magna Carta’s modern development, according to Justin Champion, a history professor at the University of London who was one of the contributing authors to Magna Carta: The Foundation of Freedom. “Coke’s dominance of the parliamentary debates, and his authoritative application of the charter, gave it a powerful institutional voice,” writes Champion. “Transformed into the constitutional forms of the rule of law and the power of Parliament, Magna Carta was mobilized to the defense of the property and liberty of free-born Englishmen.”

Coke applied his interpretations of the power of the Magna Carta to acts of Parliament as well as the king, says Howard of the University of Virginia. In Dr. Bonham’s Case, decided in 1610, Coke stated that an act of Parliament “against common right and reason” would be voided by the common law. And in his Institutes on the laws of England, Coke stated that any statute passed by Parliament contrary to the Magna Carta should be “holden for none.”

More than a century after Coke’s eloquent defense of rights under the Magna Carta, Sir William Blackstone, another giant of British law who published the first volume of his magisterial and influential Commentaries on the Laws of England in 1765, took some of those arguments a step further.

Blackstone, like Coke, maintained that the Magna Carta did not create new individual rights, but preserved those that already existed. He wrote that the charter “protected every individual of the nation in the free enjoyment of his life, his liberty and his property, unless declared to be forfeited by the judgment of his peers or the law of the land, a blessing which alone would have merited the title that it bears, of the great charter.”

But “Blackstone and his countrymen no longer subscribed to Coke’s view that acts against fundamental rights are null and void,” writes Malcolm in Magna Carta: The Foundation of Freedom. “Instead, they trusted Parliament to protect their liberties. Parliament, not judges consulting Magna Carta or any list of rights, determined what English liberties were or should be. The only check on Parliament’s actions was that its legislation be rational. Blackstone said so.”

Painting of Sir William Blackstone courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery

THE RIGHTS OF ENGLISHMEN

Independence was not on the minds of the English settlers who began arriving in America at the dawn of the 17th century. From early on, their primary concern was that they retain the same rights as their countrymen in the homeland they had left behind. It was this concern that brought the Magna Carta to the New World.

The English colonies that hugged the Atlantic coast from Massachusetts to Georgia were created largely through charters granted by the Crown to individuals or groups like the Virginia Company of London, which received the first charter in 1606. Among their provisions, these charters established councils that would have enumerated governmental powers. Significantly, the charters also contained language noting that inhabitants of the colonies shall, as spelled out in the Virginia charter, “have and enjoy all liberties, franchises and immunites within anie of our other dominions to all intents and purposes as if they had been abiding and borne within this our realme of Englande or anie of our saide dominions.”

By this time, the Magna Carta was widely viewed as the root of the “liberties, franchises and immunities of Englishmen,” and the charter would be invoked repeatedly by the colonists in asserting their rights in response to actions by the Crown and Parliament. They were, Howard writes in The Road from Runnymede, “historic words that would roll and echo down through the decades of colonial history. They would appear, in one form or another, again and again—in the charters of the other American colonies, in the statute law of colonial assemblies, in petitions against tyrannical royal governors, in the declarations of the Stamp Act Congress, in the pamphlets and writings of John Adams and John Dickinson and scores of others, in the resolutions of the Continental Congress, and finally in the Declaration of Independence.”

William Penn, a Quaker leader whose 1670 trial in London for “tumultuous assembly” helped to solidify the right to a jury trial in England, was an important early advocate of the Magna Carta in the colonies after he received a grant of land from Charles II in 1681 that became the colony of Pennsylvania. After arriving in America in 1682, Penn published the first text with commentary of the Magna Carta in the colonies five years later. Titled The Excellent Privilege of Liberty & Property Being the Birth-Right of the Free-Born Subjects of England, the commentary actually was lifted from a previous work published in England, according to Howard, which in turn was based largely on the writings of Coke.

Whatever the source, the rights now being gleaned from the Magna Carta were taking hold in the colonies just as the British government began playing a more centralized role in the governance of the colonies.

Coke’s ideas on individual rights and government powers had a particular appeal in the colonies, says Howard. On one level, the works of Coke were widely available to colonial government leaders and lawyers, so it was hard not to be influenced by his thinking. At the same time, Coke’s philosophy had a stronger appeal in the colonies than Blackstone’s theory of the supremacy of Parliament. “Americans had become accustomed over the years to self-government,” Howard says. “That’s why the tax laws were so unpopular.”

Throughout the mid-1700s, Parliament imposed a series of taxes on the colonies to help cover a growing national debt arising out of various wars and other overseas ventures, including the Seven Years’ War in Europe. The French and Indian War in North America was an adjunct to that conflict. Britain emerged victorious, and the Treaty of Paris in 1763 granted Britain hegemony over French territory in Canada along with its own colonies.

In the view of the British colonists, however, these taxes were adopted by Parliament in direct contravention of the principle from the Magna Carta that no one should be subjected to taxes without their consent. The most notorious of these measures was the Stamp Act of 1765, which imposed fees on a wide variety of products, transactions and licenses, including deeds to land, college diplomas, licenses to practice law, almanacs, newspapers and even playing cards. Moreover, charges of violating the act were to be tried in admiralty courts, where a defendant had no right to trial by jury.

The Stamp Act triggered intense, sometimes violent protests throughout the colonies, but especially in Boston—the leading mercantile center in the colonies but also a hotbed of political thinking that was beginning to question the fundamental relationship between Britain and its American colonies.

At the heart of this thinking was the conviction that, under rights granted to them as British citizens under the Magna Carta, the colonists should not be subjected to laws of Parliament to which they had not consented, especially when they compromised any of those rights. Another factor, Howard says, is what has been termed “Whig history,” the idea that history encompasses a struggle between the tyranny of old regimes and people seeking liberties. In English history, he says, it was the Anglo-Saxons who recognized fundamental rights that were later corrupted by the Normans. By the time of the Revolution in 1775, it was the colonists who viewed themselves as the protectors of those Anglo-Saxon liberties—restated in the Magna Carta—that were being ravaged by Parliament.

Another change in colonial thinking also was taking hold. “Right up to about 1774, Americans were claiming the rights of Englishmen,” says Howard, “but about then, they began to focus on the concept of natural, inalienable rights—life, liberty and property”—that ultimately found its expression in the Declaration of Independence.

Photo by Kathy Anderson

THE BILL COMES DUE

When the Constitutional Convention convened in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787 to draft a new national constitution that would take the place of the inadequate Articles of Confederation, however, its members initially focused their attention on how to structure a new government in a way that would limit its powers.

“The delegates at Philadelphia were, in short, creating an entire government,” writes Howard in The Road from Runnymede. “For such a project, Magna Carta furnished little guidance. While the charter was not in the main concerned with the distribution of governmental powers or with the shape of governmental machinery, it was very much concerned with individual rights and liberties against the state. And it was the failure of the convention to focus on these very problems of the individual and the state—at least, its failure to provide for the individual’s liberties in a bill of rights—which made the ensuing ratification contest the close thing that it was.”

The real impact of the Magna Carta became apparent in the debates within the 13 former colonies—now states—over whether to ratify the Constitution. A number of state conventions made it clear that they would not ratify the Constitution unless the drafters agreed to enumerate a list of individual rights that would be protected under the document. The result was the Bill of Rights, whose provisions echo many of the ancient rights that could be traced back to the Magna Carta.

“Our world of today was created when the Constitution went public on Sept. 16 [1787], when they published it, and over the next year as the people decided whether to adopt it,” Amar said in his Constitution Day lecture at the Library of Congress. “The Bill of Rights is all about the rights of ‘the people.’ “

Chief Justice John Roberts: “We celebrate not so much what happened 800 years ago, but what has transpired since.” Photo by Kathy Anderson.

Howard shares that view. “It is in the Bill of Rights, rather than in the body of the Constitution itself, that we find the bridge between Magna Carta in England and the charter’s legacy in America,” he writes in The Road from Runnymede.

Legal principles that can be traced back to the Magna Carta, especially the wide-ranging concept of due process as stated in the Sixth and 14th amendments, still are the sources of much of the Supreme Court’s constitutional jurisprudence, and justices still acknowledge the Magna Carta’s influence, although it has limits.

“There is no greater pedigree for a concept or principle than saying it traces its roots to Magna Carta,” says Wermiel of American University. “Magna Carta is a truly foundational document in terms of thinking about rights and thinking about government accountability, and the Supreme Court has great respect for that foundational role, not just for American law but governance the world over.” Nevertheless, he says, “Magna Carta has more symbolic influence than doctrinal importance for the Supreme Court.”

Last August, U.S. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. made that point in a speech to the ABA House of Delegates during the 2014 annual meeting in Boston. The Magna Carta is still recognized today, he said, “because it laid the foundation for the ascent of liberty” and constitutional democracy. “We celebrate not so much what happened 800 years ago, but what has transpired since.”

• Find more ABA Journal articles about the Magna Carta by clicking here.

This article originally appeared in the June 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “America’s Magna Carta: The Great Charter sealed by King John of England in 1215 is widely viewed as a direct influence on liberties and constitutional democracy in the United States.”