Alternative facts and the law: Is justice a reality?

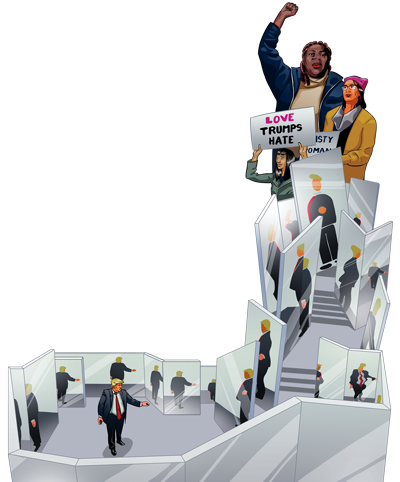

Illustration By Steven P. Hughes.

“It is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real.” —Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulation

In January, I watched two events transpire in sequence on television: the inauguration of President Donald Trump and then the women’s marches and protests that took place on the same Washington mall and throughout the world. The president’s inauguration speech was a story about American carnage, providing a bleak vision of burned-out factories in decay and decline, set pieces and selected imagery that easily could have been borrowed from the movie The Road Warrior.

The following day, there were images of massive crowds at the Women’s March on Washington: the marchers protesting the new administration, rekindling the possibilities of collective action in a media world that seldom seems to record or value the responses of people within it.

As is customary, panels of talking heads on cable TV provided commentary that affixed meanings to the surfaces of dramatic images. Pundits looked back into our past, argued over their own interpretations of events, and then inevitably were drawn forward into the future. They filled up the news cycle and provided their predictions and speculations of what the future would hold for us all, and what would happen next in a political story that no one could rightfully see or anticipate and that only becomes clear in hindsight.

Of course, this form of news programming enables viewers to tune in and out at any time, and the tension of conflict and argument always segues nicely into the endless loops of commercial interlineations. The commentaries on Trump’s first two days were akin to earlier pieces about the presidential campaigns, in which recurring casts of familiar pundits and surrogates were inevitably wrong in their predictions of what lay ahead—the tectonic plates of democracy shifting in ways that defied predictability.

SIZE MATTERS

On the second day after Trump’s inauguration, the debate twisted into a dispute not about interpretation of facts but about the underlying “facts” themselves: competing stories about the metrics of crowd size. Initially, Trump’s media surrogates claimed that the crowd size at his inauguration was “just as big” as it was at President Barack Obama’s. These crowds had been “simply tremendous” at Trump’s inauguration in comparison to the Women’s March.

There are many ways to think about the truth. For the most part, the truth in question here is not the correspondence of words to something real but the justification for particular beliefs about events. Jack L. Sammons, a legal philosopher and professor emeritus at Mercer University School of Law in Savannah, Georgia, says: “The shock of the Trump claim was the weakness of the justification for the belief. Both sides were generally in agreement on how that truth should be determined—by observations and the reports of others.”

As the data (and the images) validated the pundits’ perspective rather than the president’s, the argument shifted, as if the story could be transformed by the pull on a rhetorical lever. Then, as the late Jerome Bruner, an educational psychologist and professor at New York University School of Law, might have put it, the argument “went meta” with Kellyanne Conway arguing famously that there are no “actual facts,” only “alternative facts.” The president tweeted, and the surrogates attacked with another story: The images in various photos and the data collected were all part of a lie concocted by a villainous liberal media in a conspiracy to destroy the young presidency. (Or as Alfred Hitchcock observed, “The more successful the villain, the more powerful the story.”)

I watched with dismay. When the Trump surrogates spoke of alternative facts, I thought initially of Big Brother in George Orwell’s dystopian novel 1984—the Ministry of Truth’s “reality control” and the Party’s call to “reject the evidence of your eyes and ears,” denying reality as “something objective, external, existing in its own right.” But then I recalled an alternative framing story—Paddy Chayefsky’s masterful screenplay for Sidney Lumet’s visionary satire of television journalism in the film Network.

LIFE IMITATES ART

In Network, Howard Beale, an aging television anchorman who is about to be fired for declining ratings, suffers an on-air breakdown and is transformed into “the Mad Prophet of the Airways.” In doing so, he unleashes a ratings bonanza and TV news morphs into infotainment and reality television.

In a signature scene, Beale implores a vast audience of passive “videots” to rise from their passivity, shut off their TV screens, go to their windows and scream out into the night: “I’m as mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore.” Without hesitation, the audience obeys his command. Later in the film, Beale’s populist message is co-opted and transformed by corporate oligarchy, and Beale morphs from a celebrity to a martyr when he is assassinated on live television, resurrecting his once-again declining ratings after he finally adopts the party line.

I recast Trump in the role of the Beale character, unleashing the passive audience’s populist anger and then attempting to turn that anger back on the corporate and elitist media. Why? In part because the media had, throughout the primaries and presidential campaign, uncritically showcased Trump’s speeches and rhetoric, and also in part because, like Beale, Trump in turn had bolstered the cable networks’ ratings. And for-profit cable media adopted another effective low-cost strategy: reporting what experts on both sides think about events as sufficient to tell the “truth” about events rather than undertaking more costly (and perhaps more off-putting and less entertaining) investigative reporting characteristic of print journalism. That is, the media left it up to the audience to choose what to believe based on competing opinions, rather than on presentation of evidence.

Now under attack, the newly outraged television media claims some things are simply true; that there’s indeed a “there” there after all—and that not all beliefs are justified.

Is truth a matter of what is believed subjectively by the audience? Does it still matter whether the belief is not justified by the evidence? This is not a new question, but it is a question ever more pressing for our time. It also is a question that is especially important for lawyers.

Let’s go back in time to the mid-20th century, when academic theorists sensed that something important was afoot in how we processed information and how, in turn, these processes would redefine who we are now, and the stories we tell in constructing our worlds and our own identities within these worlds.

Marshall McLuhan, the late communications theorist and philosopher, provided what might seem, in retrospect, a naive and romantic vision of a world interconnected by newly emergent technologies into a “global village.” Baudrillard’s vision was darker: We were migrating outside ourselves, into the dangerous simulacra of unmediated images, a “hyper-reality” of free-floating narratives, a sound chamber echoing unrealities and consumerist dissatisfactions back into us. Perhaps Baudrillard now has the upper hand.

THE CRUX FOR LAWYERS

Cut to my law school classes. Students locked behind their computer screens addicted to various custom-designed cyber worlds. Are they following along with the cases? Or surfing Twitter feeds? Catching up with Facebook postings? Are classes merely a respite from texting and media and cellphone and cyberspace addictions?

I tell students in my first-year classes the practice of law anticipates the interaction between law and facts; legal doctrine matters only as applied to “the facts.” If we exist exclusively in a hall of mirrors where there are no actual facts but only alternative facts, then there may be judgment but not justice.

Many students find my perspective naive; it no longer fits their worldview. One of my students (now a lawyer) put it this way: “As a general rule, the justice system seems to favor the ‘knowable’ version of the truth. Lawyers tend to believe the opposite. By their behavior and their beliefs, lawyers view the truth as an unapproachable ideal.

“Leaving aside examples where it is so clear that an account of an event is ‘true’ or at least so clear that no one wants to bother arguing about it—the truth is unknowable. Since there is no way truth can be definitively proven, the role of the lawyer is not to aid in the search for truth, which is an oxymoronic phrase anyway, but to arrange any and all facts available to produce the story that best suits his client’s needs.”

I don’t dispute that there is some realism in my former student’s skepticism. But if the possibility of factual truth is now oxymoronic, may we permissibly gauge truth not by justified belief based on evidence but by the entertainment value of the narrative? Or by our trust in the authenticity of the voice? Or by the supposed authority and power of the speaker? Are we more like the passive videots in Chayefsky’s Network than we may care to admit?

I fear that when alternative facts become the norm, and the fair-minded application of the law to facts to achieve justice seems a naive and romantic pursuit lost in a different time, then the practice of law, like politics, is potentially transformed. We then move into dangerous, uncharted territory.

Philip N. Meyer, a professor at Vermont Law School, is the author of