A Supreme Case of Contempt

Note: Members can now listen free online to this month’s CLE, “A Turn-of-the-Century Lynching that Launched 100 Years of Federalism.”

The case was United States v. Shipp. There were nine defendants, all charged with contempt of court—contempt of the Supreme Court, that is. The U.S. attorney general had filed the charges against them directly with the court, thus giving it original jurisdiction in the matter. The petition alleged that the defendants and other people engaged in actions “with the intent to show their contempt and disregard for the orders of this honorable court … and for the purpose of preventing Ed Johnson from exercising and enjoying a right secured to him by the Constitution and laws of the United States.”

It was a full-blown trial. There were special prosecutors, dozens of witnesses and a special master assigned to take the evidence. The trial record exceeded 2,200 pages. Each side was given a full day of oral argument before the justices.

Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller, who normally encouraged his colleagues to write the court’s opinions, decided that the importance of this case demanded that he take on the responsibility. Before reading the opinion that accompanied their verdict, Fuller—in his typically soft, almost inaudible voice —noted to a packed courtroom that the Supreme Court had entered new territory for which there was no precedent.

A hundred years later, United States v. Shipp has faded into the haze of precedent and history, but legal historians say its impact remains undiminished. Shipp has been cited as the genesis of federal habeas corpus actions in state criminal cases. The case also was a pivotal turning point in asserting the importance of the rule of law and the need for an independent judiciary.

“In countries all over the world, the United States is helping develop legal systems similar to ours,” says Thomas E. Baker, a constitutional law professor at the Florida International University College of Law in Miami. “But the one thing that has been most difficult to teach is respect for the law. We had to learn it the hard way. There is no better example, there is no clearer symbolic precedent of establishing and enforcing the rule of law than this case.”

But despite its legal importance, Shipp provided the climax to an amazing story involving a cast of memorable characters—perhaps most of all two unknown African-American lawyers who, because of their tenacity and bravery, changed the U.S. justice system. As a reward for their efforts, those two lawyers saw their client murdered, their practices destroyed, their families threatened and their homes burned to the ground. Fearing for their lives, they never returned to their hometown after attending the Supreme Court hearing in Washington, D.C., on that spring day in 1909.

“This story reminds us why we became lawyers and of the important role of lawyers in our society,” says Judge John E. Jones III of the U.S. District Court in Williamsport, Pa., and a member of the executive committee for the National Conference of Federal Trial Judges in the ABA’s Judicial Division. “The lessons taught in this case are just as important today as they were a century ago.”

FOOTSTEPS IN THE NIGHT

When Chief Justice Fuller read the majority opinion in the Supreme Court’s 5-3 decision, he started with a detailed recitation of the extraordinary facts of a case that began on a dark street in Chattanooga, Tenn.

Chattanooga lies just north of the Georgia state line. The city sits in the shadows of Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, two famous Civil War battlegrounds. The mighty Tennessee River cuts through the heart of the city.

In 1906, Chattanooga—whose population of 60,000 was about one-third black—enjoyed a healthy economy built on a strong industrial base, especially iron factories and steel mills. The city had been a stronghold of Union support during the Civil War, and in the years after the war, racial friction was perhaps somewhat less charged than in many other Southern cities. One measure of that climate was the fact that Chattanooga had fewer lynchings than many other communities in the South.

Nevada Taylor, a 21-year-old white woman, lived with her father in a house at the foot of Lookout Mountain. She worked as a bookkeeper at a grocery store downtown.

On Jan. 23, 1906, Taylor left work about 6 p.m. She stepped from the electric trolley 25 minutes later and walked between some buildings as she headed toward her home. The sun had long since set behind Lookout Mountain.

Suddenly, Taylor heard footsteps behind her. Before she could turn around, there was a leather strap around her throat.

“If you scream,” the man whispered, “I will kill you.”

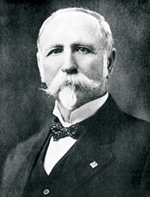

Sheriff Joseph Shipp

Photo courtesy of Mark Curriden

Twenty minutes later, Taylor regained consciousness. She ran to her house—less than 100 yards away—where her father used their newly installed telephone to call Hamilton County Sheriff Joseph F. Shipp and report that his daughter had been raped.

Jan. 24: News of the attack on Taylor spread quickly. The Chattanooga News described it as “the most fiendish crime in the history of Chattanooga.” Despite the fact that Taylor told the sheriff she didn’t see her assailant, the newspaper reported that the crime had been committed by a “Negro brute.”

Jan. 25: Sheriff Shipp and Hamilton County Judge Samuel D. McReynolds, both up for re-election in a couple of months, were hearing calls for their resignations when two days passed without an arrest in the Taylor case. They announced a $375 reward—$200 came from Gov. William Cox—for anyone who could identify the attacker.

Jan. 26: A white man named Will Hixson, who read about the reward in the newspaper, stepped forward to say that he had seen Johnson, a young black man, carrying a leather strap near the scene of the crime at about the time it took place.

Shipp arrested Johnson, who was 19 years old. Johnson had dropped out of school in the fourth grade and, by his own account, he could not read or write. Nor did he have a criminal record. During the day, Johnson did carpentry at various local churches. At night, he tended pool tables at a place called the Last Chance Saloon, which sat on the state line. North Georgia counties were dry, so this was the last chance to buy alcohol.

Despite three hours of interrogation, Johnson maintained his innocence, claiming that he was at the Last Chance Saloon all evening on the 23rd. He provided the names of a dozen men who could vouch for his whereabouts.

Recognizing that Johnson’s life was in danger—the newspapers had essentially predicted that a lynch mob would try to raid the jail to institute immediate “justice” —the sheriff and judge secretly moved Johnson by train to Nashville pending trial.

Several hundred men did raid the county jail that night—and the following night—in an effort to lynch Johnson. At one point, Judge McReynolds personally pleaded with leaders of the mob to let the courts deal with Johnson, and promised that justice would be swift.

If the mob had gotten its way, Chattanooga would have seen its first lynching since 1897—nearly a decade.

Judge Samuel McReynolds

Photo courtesy

of Mark Curriden

Jan. 28: McReynolds announced that he had appointed two lawyers, neither of whom had previously handled a criminal case, to defend Johnson. A third lawyer also stepped forward to help defend Johnson. He was Lewis Shepherd, a former judge who was widely regarded as one of the best lawyers in Tennessee. He also was well-known for representing the poor and downtrodden, and he often defended blacks charged with crimes against whites.

Jan. 29: McReynolds met with the three defense lawyers and prosecutors to announce that Johnson’s trial would commence in 10 days in Chattanooga.

Shepherd argued that they couldn’t put together an adequate defense in just 10 days. McReynolds warned Shepherd against filing a motion to stay or delay the trial. “I won’t grant it and it will only make me angry,” the judge said.

Shepherd then asked the judge to move the trial to Nashville, Knoxville or Memphis—anywhere but Chattanooga—pointing to the two lynching attempts and the newspaper articles that had unfairly tainted the local jury pool.

“Don’t file a motion for a change of venue,” McReynolds instructed. “I won’t grant it, either.”

‘I BELIEVE HE IS THE MAN’

Feb. 6: Johnson was brought back to Chattanooga for trial. Thirty-four white men were summoned to jury service. A dozen were seated.

The first witness was the victim, Taylor, who walked the jury through what had happened on the night of her attack. “I believe he is the man,” she told jurors, pointing to Johnson.

The second witness was Hixson, who had claimed the $375 for identifying Taylor’s attacker. Hixson told jurors he saw Johnson near the scene of the crime at about the time the attack took place.

But under cross-examination and later through rebuttal witnesses, it became apparent that Hixson probably wasn’t near the crime scene at all on the night of the attack. Witnesses testified that on the morning the reward was announced, Hixson had walked by the church where Johnson was working on the roof and casually obtained his identity. An hour later, Hixson was making his statement to the sheriff.

Feb. 7: Defense attorneys called 17 witnesses, including a dozen men who swore under oath that they had seen Johnson at the Last Chance Saloon at various times on the night of the attack.

Feb. 8: At the request of jurors, Taylor was recalled to the witness stand. “Miss Taylor, can you state positively that this Negro is the one who assaulted you?” a juror asked.

“I will not swear that he is the man,” Taylor responded, “but I believe that he is the Negro who assaulted me.”

A second juror rose, tears streaming down his face. “In God’s name, Miss Taylor, tell us positively—is that the guilty Negro? Can you say it? Can you swear it?” Taylor raised her left hand heavenward and said, “Listen to me. I would not take the life of an innocent man. But before God, I believe this is the guilty Negro.”

At which point a third juror jumped from his chair and started going toward the defendant with his arms raised, only to be held back by fellow jurors. He yelled out, “If I could get at him, I would tear his heart out right now!”

Feb. 9: The three-day trial ended with the jury finding Johnson guilty of rape. Judge McReynolds informed the defense attorneys that he planned to sentence Johnson to death.

When they met with Johnson, even Shepherd reluctantly went along with the advice that any attempt to appeal the conviction would be fruitless. They explained to Johnson that he could either die according to a court’s decision or at the hands of a lynch mob.

That afternoon, Johnson stood before Judge McReynolds to receive his sentence. “The jury says that I am guilty, and I guess I will have to suffer for what somebody else has done,” Johnson said. “I guess I will be punished for another person’s crime.”

McReynolds scheduled Johnson to be hanged on March 13 in the basement of the county jail.

Noah Parden

Photo courtesy of Mark Curriden

Feb. 10: Noah W. Parden and his partner, Styles L. Hutchins, were the leading black lawyers in Chattanooga. Parden had helped Shepherd track down witnesses in the Johnson case but had declined his invitation to officially join the defense team. And when Johnson’s father appeared at their office asking them to take his son’s case on appeal, Parden was still reluctant, worrying about the sensational nature of the case and the negative impact it might have on their practice.

But Hutchins pushed for them to take the case. Invoking the Bible, Hutchins said, “Much has been given to us by God and man. Now much is expected.”

Feb. 13: Parden, 41, and Hutchins, 53, stood before Judge McReynolds in open court to file a motion seeking a new trial for Johnson. They told the judge there was significant doubt about the guilt of their client, and they argued that his previous lawyers had improperly abandoned him by convincing him to waive his right to appeal.

But McReynolds quickly rejected the plea, stating that the defense attorneys had missed the deadline under local rules requiring that motions for new trial be filed within 72 hours of a verdict.

Besides, the judge scolded them, “What can two Negro lawyers do that the defendant’s previous three attorneys were unable to achieve? Do you know the law better than this court or the lawyers who represented the defendant? Do you think a Negro lawyer could possibly be smarter or know the law better than a white lawyer?”

Feb. 20: Parden and Hutchins filed an appeal with the Tennessee Supreme Court, as well as a writ of supersedeas seeking an emergency stay of execution.

March 3: In a unanimous ruling, the court denied the appeal.

ENTER THE FEDERAL COURTS

Styles Hutchins

Photo courtesy of Mark Curriden

March 7: Parden and Hutchins filed a petition in U.S. District Court in Knoxville under the 1867 Habeas Corpus Act, which allowed defendants in state criminal cases to ask federal judges to review their cases if they believed they had been imprisoned in violation of their federal constitutional rights. But those rights wouldn’t be fleshed out by Congress and the courts for several more decades, and in 1906, lawyers agreed that federal habeas petitions were pretty much useless.

The nine-page petition pointed out that Johnson’s original lawyers were denied the right to file pretrial motions, that the trial was unfairly influenced by the threat of mob violence, that only white people were summoned to jury service, that Johnson’s lawyers abandoned their client by advising him to waive his rights to appeal, and that there were numerous irregularities during the trial, including the fact that a juror tried to attack the defendant in the middle of the trial.

Hours later, Judge C.D. Clark agreed to hold a hearing to allow Parden and Hutchins to present evidence and make arguments.

March 10: The habeas hearing in federal court lasted more than eight hours. Among the witnesses called by Parden and Hutchins—who had been joined by Shepherd—were the other two of Johnson’s original lawyers. They largely confirmed the allegations in the habeas petition, including how the threat of the lynch mob influenced their decisions. A deputy in the Hamilton County clerk’s office testified that he remembered only one black person ever being called for jury service in Chattanooga.

Hamilton County District Attorney Madison N. Whitaker argued that there had been no violation of Johnson’s federal rights. And Judge McReynolds himself insisted the trial had been fair.

March 11: After deliberating in his chambers for more than three hours, Judge Clark returned to the bench to announce his decision at 12:47 a.m. He pointed out that “counsel were to an extent terrorized on account of the fear of a mob.” He also expressed doubts about the state’s case against Johnson. He ruled that he was not empowered by the Constitution to grant the habeas petition, but he did issue a 10-day stay of execution, permitting Johnson’s lawyers to appeal directly to the U.S. Supreme Court.

March 12: In an interview with the Chattanooga News, Judge McReynolds asserted that federal judges do not have authority to issue stays in state criminal cases.

March 13: Gov. Cox granted Johnson a seven-day stay of execution—three days fewer than the federal court. More newspaper articles quoted McReynolds and several lawyers saying that the appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was frivolous and would be quickly rejected.

March 14: In Chattanooga, a grand jury was convened to investigate the lynching attempts against Johnson before his trial. But Judge McReynolds testified that he could not remember a single person he saw on the night he addressed the mob. The grand jury issued no charges in the incident, but it did indict three black men for stealing two mules.

March 15: At 1:30 a.m., a group of men set fire to the law office of Parden and Hutchins. At 3 a.m., men threw rocks and fired gunshots through the windows of Parden’s home while his wife, Mattie, was there alone. A prominent local minister and educator, the Rev. T.H. McCallie, allowed Mattie to stay with his family while Parden journeyed by train to Washington to pursue Johnson’s appeal.

March 16: Parden filed the official appeal of the denial for federal habeas with the U.S. Supreme Court clerk. He was assisted by Emanuel D.M. Hewlett, one of the few black members of the Supreme Court bar, whose experience was limited to serving as co-counsel in one earlier case. This would be the first time a black lawyer served as lead counsel in a case before the court.

March 17: Parden made his arguments directly to Justice John Marshall Harlan, a Kentuckian who was assigned to hear emergency appeals from within the 6th Circuit.

Harlan, who was born two years before the death of his namesake, the great Chief Justice John Marshall, came from a slaveholding family but had served in the Union army during the Civil War. In 1896, Harlan had issued a scathing dissent when the court upheld the separate-but-equal doctrine in Plessy v. Ferguson.

Parden pointed to specific violations of the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and 14th Amendments. “The atmosphere in the community was so poisoned that there was no way Ed Johnson could have received a fair trial from an impartial jury,” Parden said. “Everybody in that courtroom knew going in what they were going to do. They were there to give Ed Johnson a trial, and then they were going to hang him.”

March 18: Parden stepped from the train in Chattanooga, greeted by Hutchins, who waved a single sheet of paper in the air—a telegram from Washington, D.C.: “Have allowed appeal to accused in habeas corpus case of Ed Johnson. Signed: John M. Harlan, associate justice.”

A TRIUMPH FOR MOB LAW

March 19: News of Justice Harlan’s action spread throughout Chattanooga. Dozens of men, armed with guns, stormed the county jail holding Johnson. Leaders of the mob were surprised to find no resistance to their raid. Sheriff Shipp, claiming that talk of a lynching was nonsense, had given all of his deputies the night off—all except 72-year-old jailer Jeremiah Gibson. And all the other inmates had been moved off the floor where Johnson’s cell was located.

The siege on the jail began about 8 p.m., with mob leaders using sledgehammers to pound away at the big iron lock that protected Johnson in his cell. Sheriff Shipp actually showed up at the jail amid the riot, but he was told to go into the bathroom and wait. He complied.

Photo courtesy of Mark Curriden

It took three hours for the iron lock on Johnson’s cell to finally give way. The leaders of the mob grabbed him and took him to the county bridge that spanned the Tennessee River. They put a noose around Johnson’s neck and told him that there was nothing he could do or say to save his life, so he might as well confess.

But when he spoke, according to newspaper reports, Johnson said, “I am ready to die. But I never done it. I am going to tell the truth. I am not guilty. I am not guilty. I have said all the time that I did not do it and it is true. I was not there.”

Then Johnson uttered his last words: “God bless you all. I am innocent.”

The statement drove the crowd into a frenzy, and Johnson was lifted into the air by his neck. His body swung for a couple minutes. But he apparently wasn’t dying fast enough, so some in the mob opened fire. One report stated that he was shot more than 50 times. Finally, a bullet pierced the rope and Johnson’s body fell to the wooden planks of the bridge.

“He’s not dead yet!” yelled someone in the crowd.

A man later identified as a deputy sheriff shot Johnson five more times at point-blank range. He then pinned a note onto Johnson’s chest that read, “To Justice Harlan. Come get your n—-r now.”

THE SUPREME COURT RESPONDS

In Chattanooga, most white leaders decried the lynching as awful and a blemish on the image of their progressive Southern city. But many of them also said the whole thing wouldn’t have happened if the U.S. Supreme Court had stayed out of a local criminal case.

Eight days after the lynching, Shipp and McReynolds were re-elected in landslides.

In Washington, the Supreme Court justices, along with President Theodore Roosevelt and officials at the Justice Department, learned about the lynching the next morning. The news quickly triggered discussions about initiating a federal investigation.

Meanwhile, newspaper reports began to address the implications of the lynching.

“Johnson was tried by little better than mob law before the state court,” Justice Harlan told the Washington Post. “He had the right to a fair trial, and the mandate of the Supreme Court has for the first time in the history of the country been openly defied by a community.”

An article in the New York Times stated, “The open defiance of the Supreme Court of the United States has no parallel in the history of the court. No justice can say what will be done. All, however, agree in saying that the sanctity of the Supreme Court shall be upheld if the power resides in the court and the government to accomplish such a vindication of the majesty of the law.”

U.S. Attorney General William Moody sent two Secret Service agents to investigate the lynching. For three weeks, the agents interviewed scores of eyewitnesses whose statements pointed to one conclusion: There was a conspiracy between the sheriff, his deputies and leaders of the lynch mob to kill Johnson.

On May 28, Moody did something unprecedented, then and now. He filed a petition charging Sheriff Shipp, six deputies and 19 leaders of the lynch mob with contempt of the Supreme Court. The justices unanimously approved the petition and agreed to retain original jurisdiction in the matter.

That very day, Shipp gave an interview to the Birmingham News in which he said, “The Supreme Court of the United States was responsible for this lynching. I must be frank in saying that I did not attempt to hurt any of the mob and would not have made such an attempt if I could.”

On Oct. 15, Shipp and his fellow defendants became the only individuals in U.S. history to stand before the Supreme Court justices to enter pleas of “not guilty” and to post bond.

The key legal argument brought in a motion to dismiss by the defendants was that the U.S. Supreme Court did not have authority to intervene in a state criminal proceeding by means of federal habeas. The motion also argued that the court did not have legal power to stay Johnson’s execution or to declare him a federal prisoner while it considered his habeas petition. Because the Supreme Court’s original order staying Johnson’s execution was invalid, they argued, the justices could not legally find the sheriff and others guilty of violating an illegal order.

It was an argument that made sense to a lot of lawyers and judges around the country.

But on Dec. 24, a unanimous Supreme Court, in an opinion authored by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, rejected the defense motion and the arguments made to support it.

“This court, and this court alone, has jurisdiction to decide whether a case is properly before it,” wrote Holmes, “and until its judgment declining jurisdiction is announced, it has authority to make orders to preserve existing conditions, and a willful disregard of those orders constitutes contempt. The power and dignity of this court are paramount.”

JUSTICE ON THE FLY

The trial officially began on Feb. 12, 1907. The proceedings were virgin territory for all involved, including the justices. To oversee the taking of testimony and the admission of evidence, the court appointed its deputy clerk as special master. For the sake of efficiency, the presentation of witnesses, as well as cross-examinations, took place at the federal courthouse in Chattanooga—nine blocks from the spot where Johnson was lynched. The justices did not attend those proceedings.

For more than a year, prosecutors and defense lawyers battled over a variety of legal motions. Ultimately, the justices dismissed charges against all the defendants except Shipp (who had been trounced in another bid for re-election in 1908) and eight others.

On March 2, 1909, the lawyers gathered in the Old Senate Chamber in the U.S. Capitol—where the Supreme Court had been holding its sessions since 1860—this time for closing arguments. Each side was given a day to summarize its case.

Attorney General Charles Bonaparte (Roosevelt had named Moody to the court) chose to make the prosecution’s six-hour closing argument himself. “This proceeding is unique in the history of courts,” he told the justices. “Its importance cannot be overestimated. Lynchings have occurred in defiance of state laws and state courts without attempt, or at most with only desultory attempt, to punish the lynchers.”

Furthermore, said Bonaparte, “never in its history has an order of this court been disobeyed with such impunity. Justice is at an end when orders of the highest and most powerful court in the land are set at naught. Obedience to its mandates is essential to our institutions.”

Over five days in late April, the justices met in conference—essentially, these were jury deliberations. A consensus gradually developed among five of the eight justices deliberating the case. (Moody, who joined the court in 1906, had recused himself.)

But the justices were divided on the meaning of the verdict. Some argued it was exclusively about enforcing the integrity of the court. Others believed the court needed to send a message to states that lynch law would not be tolerated.

Chief Justice Fuller addressed both points when he read his majority opinion on May 24, 1909, finding Shipp, one of his deputies and four leaders of the mob guilty of contempt.

“It is apparent that a dangerous portion of the community was seized with the awful thirst for blood which only killing can quench,” Fuller stated. “The persons who hung and shot this man were so impatient for his blood that they utterly disregarded the act of Congress as well as the order of this court.”

When anyone in custody “is at the mercy of a mob,” Fuller continued, “the administration of justice becomes a mockery. When this court granted a stay of execution on Johnson’s application, it became its duty to protect him until his case should be disposed of. And when its mandate, issued for his protection, was defied, punishment of those guilty of such attempt must be awarded.”

Six months later, on Nov. 15, the defendants appeared before the justices one more time to hear their sentences: Shipp and two others were ordered to serve 90 days in jail, while the others were sentenced to 60 days, all at the U.S. jail in the District of Columbia.

Like his co-defendants, Shipp was released early. Returning to Chattanooga by train on Jan. 30, 1910, he was greeted with a hero’s welcome by more than 10,000 cheering supporters. Later, a monument was erected in his honor. Judge McReynolds went on to serve in Congress for 18 years.

Fearing for their lives, Noah Parden and Styles Hutchins never returned to Chattanooga. Hutchins moved to Taft, Okla., but there is no indication that he ever practiced law again. Parden and his wife moved to East St. Louis, Ill., where he practiced law for nearly four more decades.

If a lynch mob had not murdered Johnson, his case before the Supreme Court might have spelled greatness instead of obscurity for Parden, who likely would have been the first African-American lawyer to argue a case before the court. Every one of Parden’s constitutional arguments in Johnson’s case were eventually affirmed by the Supreme Court—that the right to a fair trial is undercut by the threat of mob violence; that defendants must be afforded the right to effective counsel; that criminal trials must be open to the public; that there is a federal right to a fair trial in state criminal proceedings; that states may not systematically exclude potential jurors because of race; and that state criminal defendants have a right to federal habeas corpus proceedings.

May 24, 1909, stands out in the annals of the U.S. Supreme Court. On that day, the court announced a verdict after holding the first and only criminal trial in its history.

After the proceedings ended, Parden told the Atlanta Independent that the importance of the case reached far beyond its specific legal outcome. “The very rule of law upon which this country was founded and on which the future of this nation rests has been enforced with the might of our highest tribunal,” said Parden. “We are at a time when many of our people have abandoned the respect for the rule of law due to the racial hatred deep in their hearts and souls. Nothing less than our civilized society is at stake.”

Ed Johnson is buried in a dilapidated old cemetery on Missionary Ridge above Chattanooga. His headstone is still there, almost toppled over in disrepair. But there are words still clearly chiseled into the stone. “Farewell until we meet again in the sweet by and by” is the message on the back of the stone. On the front are reflected Johnson’s words from that awful night a century ago: “God Bless you all. I AM A Innocent Man.”

ABA Connection offers three easy ways to get low cost/no cost CLE credit

Live Call-in Teleconferences

This month’s “A Turn-of-the-Century Lynching that Launched 100 Years of Federalism,” is from 1-2 p.m. ET on Wednesday, June 17.

To register, call 1-800-285-2221 between 8:30 a.m. and 6:30 p.m. (ET) weekdays starting May 26, or go to . Multiple participants may listen via speakerphone, but each individual who wants CLE credit must register separately.

Multiple participants may listen via speakerphone, but each individual who wants CLE credit must register separately.

Co-Sponsor: General Practice, Solo and Small Firm Division.

Online Access—At No Cost

Online Streaming Audio, available starting June 22. To register, go to abanet.org/cle. Past programs are available here.

CLE on Podcast

Podcast downloads are available starting June 22.

Coming in July: “The Patent Law Cure”

Sidebar

A Shameful History

Old Supreme Court Chambers in the U.S. Capitol

Photo courtesy of Mark Curriden

In 1892, Alabama’s Tuskegee University developed a very specific definition for a slaying to qualify as a lynching. A racially motivated hate crime was not a lynching unless the group participating in the killing numbered three or more, and its members had “acted under the pretext of service to justice, race or tradition.”

Between 1882 and 1951, Tuskegee documented 4,730 lynchings in the United States under that definition.

The term lynch law reportedly originated during the American Revolutionary War when Virginia Justice of the Peace Charles Lynch ordered the extralegal punishment of a colonist who remained loyal to Britain. But after Reconstruction, white Southerners institutionalized lynching as a means of terrorizing, intimidating and controlling black people. While most lynchings involved hanging, some victims were shot, burned at the stake, dismembered or in other ways tortured to death.

While racism was the predominant force behind most lynchings, Tuskegee reported that at least 1,293 of the lynching victims were white, and most of those lynchings took place west of the Mississippi. Aside from Johnson and Shipp, only a few cases involving lynching and mob violence surfaced at the U.S. Supreme Court.

Atlanta pencil factory manager Leo Frank, a white man, was convicted of raping and killing a 13-year-old girl. A mob occupied the courtroom and surrounded the courthouse throughout the trial. When the Supreme Court declined to intervene in the case, Frank v. Mangum (1915), Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote in dissent, “Mob law does not become due process of law by securing the assent of a terrorized jury.” The governor of Georgia, believing that Frank was innocent, commuted the sentence to life in prison. But two months later, a mob raided the prison where Frank was being held and lynched him.

Eight years later, Holmes prevailed in an effort to reverse the convictions of six black men sentenced to death in Arkansas. In the court’s 6-2 decision in Moore v. Dempsey (1923), Holmes wrote that “if any prisoner by any chance had been acquitted by a jury, he could not have escaped the mob.”

A Case of Firsts

Legal experts say that United States v. Shipp and its predecessor case, Tennessee v. Johnson, forever changed the practice of criminal law in the United States. Between them, the cases featured:

• The first grant of a federal habeas corpus petition by the U.S. Supreme Court in a pending state criminal case.

• The first stay of execution issued by the full Supreme Court in a state death penalty case that declared the state defendant to be a federal prisoner.

• The first time in which a black lawyer was lead counsel in a case before the Supreme Court.

• The first and only time in history that the Supreme Court retained original jurisdiction in a criminal case.

• The first criticism of state elected officials and courts by the Supreme Court for conducting criminal trials under the influence of the threat of mob rule, thus denying a defendant the right to a fair trial and undermining the rule of law.

Mark Curriden, a contributor to the ABA Journal, is a freelance writer based in Dallas. He is co-author, with Leroy Phillips Jr., of Contempt of Court: The Turn-of-the-Century Lynching That Launched a Hundred Years of Federalism, published in 1999.