Ramsey Clark's 70 years of political and legal activism memorialized on film

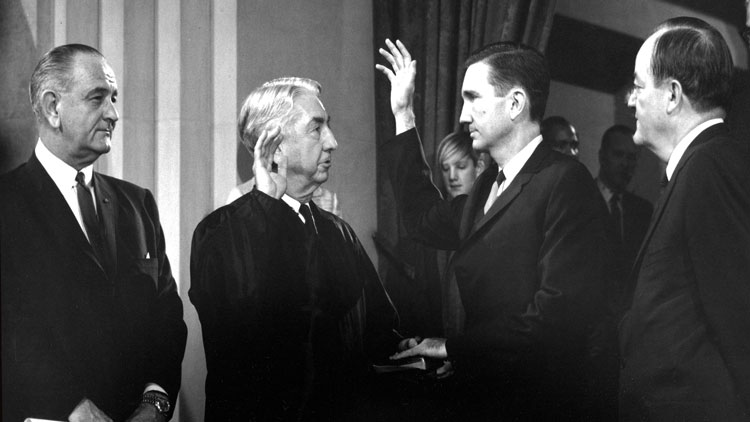

The swearing in of Ramsey Clark. photos Courtesy of Joseph Stillman/"Citizen Clark … A Life of Principle"

Ramsey Clark’s career defies categorization.

Those who came of age in the 1960s know Ramsey Clark for his leadership in the Department of Justice, where he worked with President John F. Kennedy and Attorney General Robert Kennedy and became attorney general under President Lyndon B. Johnson. A key player in the civil rights movement, the Dallas-born lawyer helped draft the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

Those who came of age in the 1970s know Clark for his criminal justice advocacy and his alignment with causes considered radical at the time, like anti-war activists and the Black Panther Party.

Years later, in the ’80s, ’90s and 2000s, Clark was known for his global anti-war activism and for representing clients ranging from controversial to despicable, including Yasser Arafat, Branch Davidian members, Slobodan Milosevic and Sheikh Omar Abdel-Rahman. Clark regularly traveled into active conflict zones to document human rights abuses, and he even wrote a book detailing what he described as war crimes committed against the people of Iraq by the U.S. government. A former law partner described him this way: Clark goes where he thinks people are hurting.

The new documentary Citizen Clark … A Life of Principle, currently on Amazon.com, provides an overview of Clark’s incredible decadeslong, multidimensional career and his intense, complex and often-controversial commitment to justice and the rule of law. As the American people search for meaning in the lives of mavericks and activists, it may be the perfect time for a new generation to discover Clark, a 65-year American Bar Association member.

Not that he’s gone anywhere. Although he’s admittedly slowed down since leading a delegation to Syria in 2015 (he’s approaching 91, after all), Clark remains dialed in to current events and optimistic about the future—as long as Americans continue rising to their responsibility.

You served the entirety of the Kennedy administration and were LBJ’s attorney general. Could you tell at the time that you were in the middle of what would be such a legendary period of history?

I knew it was an exciting time, but I don’t know if I was able to identify its comparative place in history. I know that JFK was just an incredibly inspiring guy.

Do you remember where you were when you heard he had been assassinated?

I [was] at my desk and a guy in my office called and said, “Turn on the radio,” and I turned it on, and heard that Kennedy was assassinated in my hometown. I had helped to plan the trip, and they had wanted me to go, but I didn’t want to go and didn’t. I didn’t want to go because I wanted the focus to be on him—not that I would be much of a distraction, but there would be people shouting at me. I had done what I could in organizing, and of course, it ended in unbelievable tragedy and sorrow. That was about the only time in my life where I thought, “This is it—I will never be happy again.”

You were front and center during the civil rights era. Not only did you draft landmark legislation, but you were actually there, participating. Tell me about your role in the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march.

I was in charge of protecting the marchers. I spent the whole night going back and forth through Selma, all the way down the 60-mile march, looking for any sign of anybody intruding. And I found places for them to camp. The first night, a farmer had agreed [to host the marchers on his land]. I think I tried to pay him. [He said], “I am sorry, here’s your money, you can’t stay up on my property. I’ve been threatened, and my wife says you can’t stay.” Fortunately, there was a little park on the way. … That first night, I felt like we were in the Civil War. We had campfires, and we were looking out for people to come to shoot us. But we got through to the big rally in front of the state capitol. I was on a plane going to fly back to Washington after eight days … when we got the call that a woman had been killed; a labor leader from the Midwest. She was helping drive people back to Selma. She was in a car with three or four African-American people. ... And somebody pulled up alongside with a pistol and shot and killed her. I think they also killed the guy in the front seat with her and the car wrecked. I got that message while we were over Richmond, starting to come and land in D.C., at an Air Force base on the east side of the river, close to Washington, D.C. We turned right back around. Our happy ending was marred by the murder of those two people. You always wonder whether, if we had had our guard up, we could have avoided it, but I doubt it. There’s no way of stopping all the cars. … This car just pulled up and fired a pistol into the car. … We turned around and flew back to the capital to see her body and carry it back home.

This article was published in the November 2018 ABA Journal magazine with the title "A Great Responsibility."