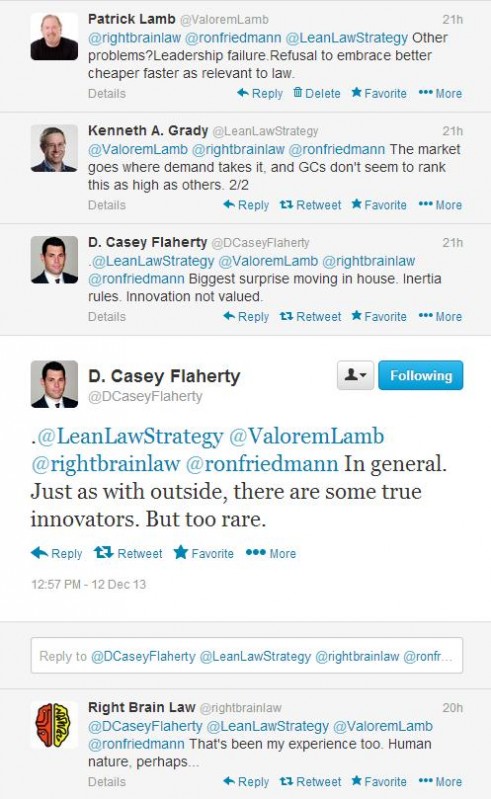

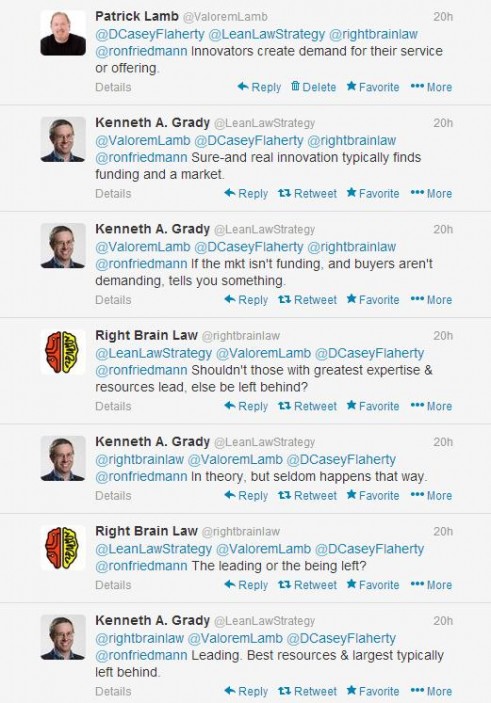

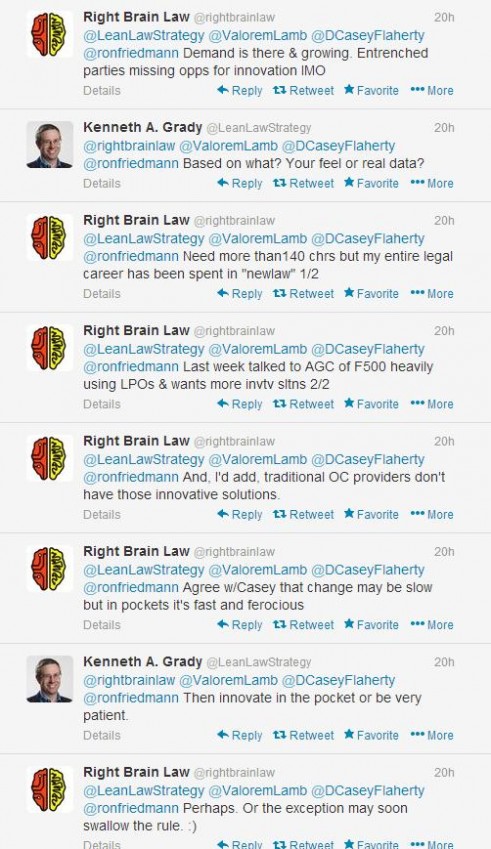

I recently had an interesting Twitter conversation with Ken Grady, Ron Friedmann, Casey Flaherty and Daniel Lear. Ken Grady is the highly innovative and highly accomplished former general counsel of Wolverine Worldwide, and is now the president and CEO of Seyfarth Lean. Ron Friedmann is the author of prismlegal.com and is a “lawyer, marketer, blogger, ex-econometrician and ex-strategy consultant.” Significant people. Here’s the Twitter conversation:

As I reflected, it occurred to me that in this group, innovation is taken for granted, and certainly Ken Grady and Ron Friedmann have substantial experience and built-up credibility in this area. Because of that, though, the difficulty of innovating is really not addressed.

There are similarities and differences between innovation and change. Change is about doing something different. Innovation is about developing a new idea to meet an articulated or inarticulated need. According to Wikipedia, Innovation differs from invention in that innovation refers to the use of a better and, as a result, novel idea or method, whereas invention refers more directly to the creation of the idea or method itself.

Innovation differs from improvement in that innovation refers to the notion of doing something different rather than doing the same thing better.

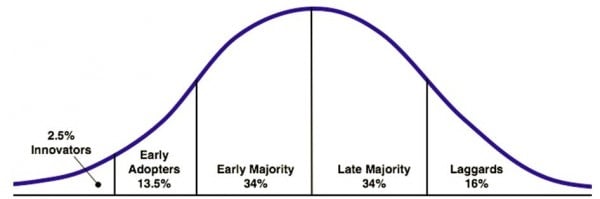

My colleague Paul Lippe has written frequently about the technology adoption curve and how it applies to change, using a concept developed in the 1950s by some academics at Iowa State University. As adopted, the concept looks like this:

The innovators are the people who do new things, frequently seeing a need the market has yet to recognize or understand. Their efforts help create awareness of the benefit of the innovation, so they are frequently in the position of first convincing others that the need exists and then offering the solution or benefit of the innovation.

Early adopters are the ones who hear the message of the innovators and are willing to try something new to meet the need. Early adopters are critical to the creation of an early majority because they are the ones from which anecdotes and then data showing the benefit of the innovation are generated, which provides comfort for the early majority.

The laggards are the people who prefer rotary telephones and writing with quill pens and for whom change occurs only when there standard way of life is no longer supported (it is really hard to find a good quill pen these days).

As adoption moves from early adopters to people in the early majority and then the late majority, the move becomes less innovation and more a change. The new ideas are no longer innovations. Starting to use an iPad in court today would be a change for many, but it is no longer innovative.

Change is extraordinarily hard. It requires a rewiring of the mind and “muscle memory” that has moved activity from the conscious brain to the unconscious brain. It is hard to describe just how hard it can be, especially when you are “unlearning” a lifetime of habits. To achieve change, you need to go through the process of making the new action, thought or whatever become part of your subconscious mind. Think about the difference between saying the alphabet forward and saying it backward. How much training would it take so that you could recite the alphabet at the same speed and accuracy regardless of direction?

As hard as change is, it pales in comparison to how damnably hard innovation is—creating a whole new idea to meet a recognized need, or even harder, to meet a need that those who have it have yet to recognize. Because it is so damnably hard, there are very few innovators (see curve above). There is, perhaps, some issue about whether innovation is a decision at all. While the Twitter discussion replayed above makes it seem like innovation is a choice, it is probably truer that for those who attempt to innovate, it is an irresistible impulse.

But whether we recognize people as innovators, accelerators of change, appliers of established ideas in new areas, change facilitators or something akin, we should acknowledge such people for their contributions to the profession and to our lives. Even if we don’t like a particular change or innovation, it is hard to argue against choice. It is even harder to argue that, over time, these innovations and changes become the new accepted norm. Remember when no lawyer used a computer? Remember when cellphones were unprofessional? Remember when no one used email?

To pay tribute to all innovators, and in the spirit of year-end lists, use the comment section to name your favorite innovation in the practice of law!

Patrick Lamb is a founding member of Valorem Law Group, a litigation firm representing business interests. Valorem helps clients solve their business disputes and cope with pressures to reduce legal spend using nontraditional approaches, including use of nonhourly fee structures, coordination with LPOs or contract lawyers, joint-venturing with other firms and implementation of project management tools to handle lawsuits or portfolios of litigation.

Pat is the author of the book Alternative Fee Arrangements: Value Fees and the Changing Legal Market. He also blogs at In Search Of Perfect Client Service.