From the depths of addiction to helping attorneys overcome their own, lawyer and author Brian Cuban has made his mark

Brian Cuban.

In 2006, the Dallas Mavericks were in the NBA finals. The team’s owner, Mark Cuban, gave two tickets for the opening game to his brother Brian to give to friends. But the younger sibling had other plans: He traded them to his drug dealer for $1,000 worth of cocaine.

In looking to profit from the ducats, selling them on eBay wasn’t an option. “That would have been disrespectful to my brother,” he tells me. “But trading them to my cocaine dealer was perfectly acceptable.” That, he explains, is “how the mind works in addiction.”

It’s something that Brian Cuban knows well. He was an alcoholic while a student at Penn State University and the University of Pittsburgh School of Law. Afterward, he moved to Dallas to practice law—and did so for years as a coke addict.

“I’ve done cocaine in the federal courthouse in Dallas. I don’t say that as a matter of pride,” Cuban says. “I say that as a matter of addiction. This is what it is.”

He has long since recovered from his addictions and moved on to become the author of a memoir, a speaker on substance abuse and now a first-time novelist. During a wide-ranging phone interview, Cuban, 60, talked of his path to addiction and recovery and his soon-to-be-published novel that tells the tale of a lawyer with his own addiction problems who becomes a fugitive after being charged with murder.

Telling stories, offering hope

While Cuban never lost his law license or was disciplined by a state bar, he no longer practices. Instead, he’s dedicated himself to speaking to law firms and bar associations about addiction. He’s quick to point out he’s no expert. Rather, he offers lessons through personal accounts. “I’m an expert in nothing but my story,” Cuban says. “I have nothing to offer but my experience, strength and hope. And that’s what I love doing.”

He shared his story in The Addicted Lawyer, a 2017 memoir, a compelling look at a life out of control and eventual recovery.

Cuban has been sober since April 8, 2007, after waking up from a two-day alcohol and cocaine-induced blackout and realizing he was on the brink of losing the love of his father, two brothers and girlfriend (who is now his wife). Even contemplation of suicide two years earlier—when he practiced firing a gun in his mouth—hadn’t been enough to change his behavior.

His journey to addiction began early. Cuban grew up in Pittsburgh. He was overweight, which caused him to be bullied and fat-shamed in junior high and high school. It led to an overwhelming desire for acceptance and a very negative self-image. Depression, Cuban says, was his “normal” long before drug and alcohol addiction. By 16, he was a “veteran at drinking.”

Cuban headed to Penn State, where alcohol consumption became essential to his sense of confidence around others. He also took on other unhealthy behaviors, such as eating and purging and becoming exercise bulimic, compulsively exercising (running 10-20 miles per day) for the purpose of burning calories.

He recalls the moment the bells went off to go to law school. “These weren’t the bells of being Clarence Darrow or emulating Atticus Finch,” he says. “If I can get into law school, that’s three more years where I can engage in the behaviors that got me though Penn State. In my mind, survival behaviors.” The decision made “perfect sense,” Cuban tells me.

Cuban had no desire to hang out with classmates “and be reminded of what I’d never be—a real lawyer,” he says. “I stayed to myself and nursed my own obsessions—exercise, alcohol and avoiding looking myself in the mirror.”

Looking back at his 1L moot court argument, Cuban says his biggest concern wasn’t discussing the finer points of the Fourth Amendment. It was “not getting close enough to [the judges] so they could smell the booze on my breath.”

He graduated from Pitt Law School in 1986 and moved to Dallas, where both of his brothers were living.

Practicing law and doing cocaine

A year after arriving in Dallas, Cuban had his first encounter with cocaine. He was in the downstairs bathroom of the city’s posh Crescent Court Hotel. “It was literally nothing I had ever experienced before in my life,” he recounts. “This feeling of self-love and confidence. All of a sudden, Brian loved Brian for the first time. All the girls I was now going to talk to upstairs loved Brian.”

In that moment, Cuban says, his anxieties seemed trivial and the formerly impossible was possible. “I was instantly addicted,” he says. “I instantly felt I couldn’t survive if I didn’t try to maintain such a wonderful feeling.”

As a lawyer in Dallas, Cuban had brief stints as a claims adjuster for insurance companies and worked for the city as a right-of-way agent, securing easements for drainage projects. He also did plaintiff’s personal injury work. He knew some chiropractors from his days as a claims adjuster, and they let him sit in their waiting rooms, engagement letters in hand, and sign up clients.

How do you practice law while doing cocaine? “Not very well,” Cuban responds without needing time to ponder.

“It was not uncommon for me to be doing lines of coke throughout the day to counteract lack of sleep and a hangover,” he says. “Many in the profession may argue that this is a form of stealing from clients when they pay for competent performance and receive less. I would have to agree.

“Did I know it was wrong? Yes. Did I know I could get arrested? Yes. Did I know I could lose my license? Yes. Of course, I did; I was suffering from substance use disorder, I wasn’t suffering from stupid disorder.”

From recovering addict to novelist

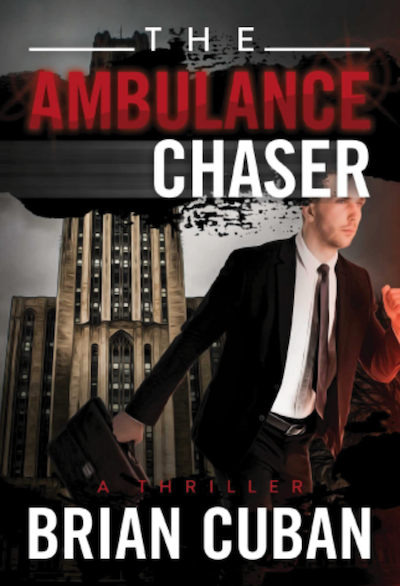

In early December, Cuban’s novel will be released. The Ambulance Chaser is the story of Jason Feldman, a personal injury lawyer and part-time drug dealer charged with the murder of a high school classmate who went missing 30 years earlier. Feldman becomes a fugitive in search of a childhood friend who can clear his name.

“I’m a storyteller,” Cuban says. “So it’s a natural progression to tell a story … that has elements of who I am as a person.”

The genesis of the book is a recurring dream in which Cuban is a young boy throwing bodies into a fire and watching them burn. “All of a sudden, I’m an adult,” Cuban says of the nocturnal image, “worrying about whether these bodies will be discovered and wondering why I haven’t been arrested yet.”

“The protagonist has elements of Brian in him,” Cuban says. “He is an ethically comprised—or walking the line—personal injury lawyer. He has troubles with drug and alcohol addiction.”

The new novelist’s older brother gives the title high praise. “The book is amazing,” Mark Cuban tells me by e-mail. “I’m so proud of Brian,” the well-known entrepreneur adds. “He worked hard for everything he has accomplished. And now he has set a new goal to become a fiction author and crushed it again.”

Lawyers still struggling

Cuban knows that addiction is not uncommon in the profession. A study published in 2016 funded by the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation and ABA Commission on Lawyer Assistance Programs found that 20.6% of the nearly 13,000 lawyers surveyed scored at a level consistent with problematic drinking.

More recently, a 2021 survey of nearly 3,000 members of the California Lawyers Association and D.C. bar revealed that approximately 30% screened positive for high-risk hazardous drinking. [The study authors acknowledged that, while efforts were made to account for an impact of the pandemic, its effect could not be ruled out.]

Cuban tells me the lawyers he speaks to and works with who struggle with substance use indicate the pandemic has had a “huge impact, especially amongst the solo and small firm practitioners. Those are the most isolated.”

He points to various reasons why many lawyers do not seek help. The law is a “profession of thinkers,” he says. “Lawyers tend to believe that they can think their way out of a problem.”

He also attributes their reluctance to stigma. Lawyers view vulnerability as a “weakness,” Cuban says. “But vulnerability is one of the prime linchpins of recovery—the ability to walk into a safe space and just pour out your shame and your pain.”

Some lawyers also fear that seeking help for addiction could lead to character and fitness problems with their state bars. “So why even risk it?” becomes the prevailing thought, Cuban says. “Better to kick the can down the road.”

As I was wrapping up our interview, Cuban asked if he could add one more thing. The former addict has advice for those whose struggles he knows: “Dropping that wall of shame, in a safe place, for just a millisecond and stepping forward,” he says, “can be the road to such a fulfilling life that you never imagined.”

See also:

ABAJournal.com: “COVID-19 hasn’t stopped this lawyer from advocating for wellness and recovery”

ABAJournal.com: “Quest for Perfection: Brian Cuban talks about lawyers and body image (podcast)”

Randy Maniloff is an attorney at White and Williams in Philadelphia and an adjunct professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law. He runs the website CoverageOpinions.info.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.